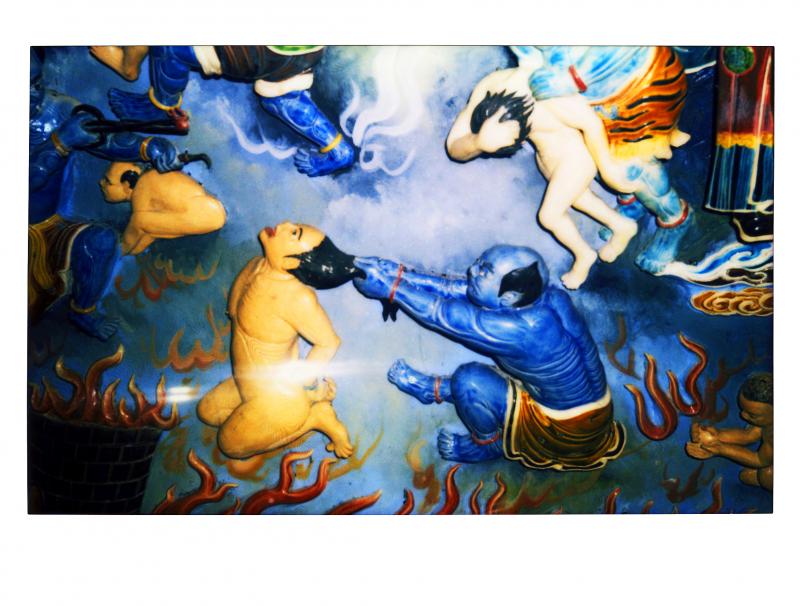

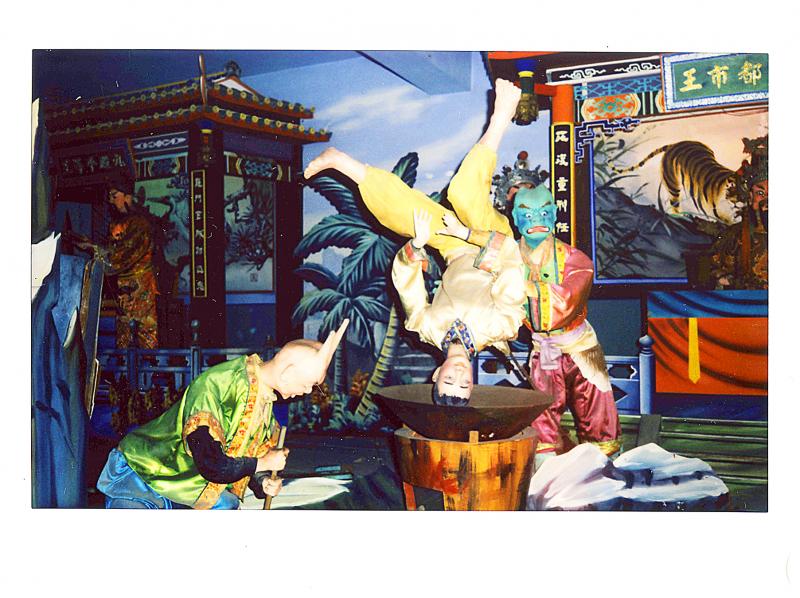

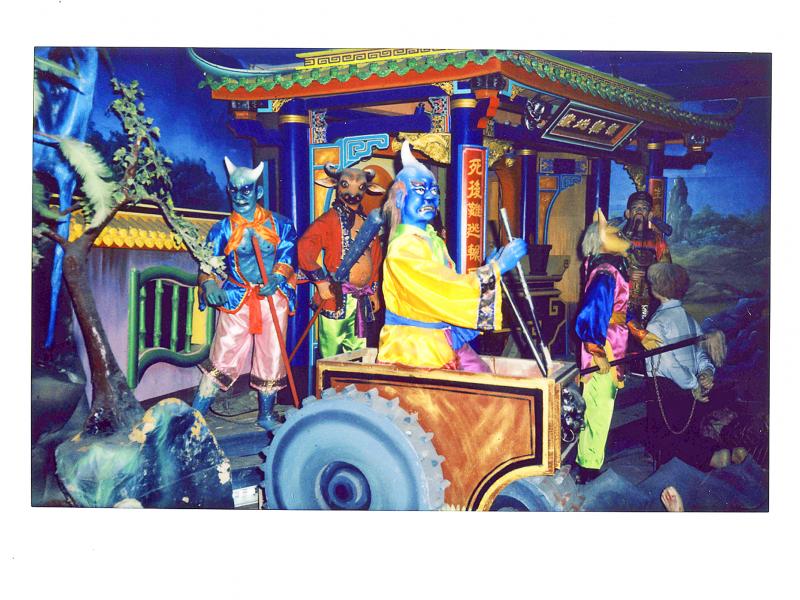

Yao Jui-chung (姚瑞中) recites a Buddhist sutra each time he visits hell. The grotesque scenes in there are not for the squeamish, with demons dumping people in pots of scalding oil, pulling their tongues out and gouging out their eyes.

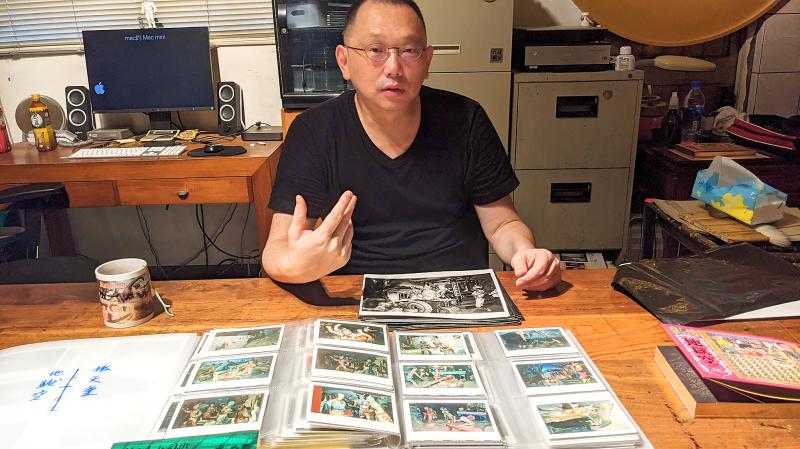

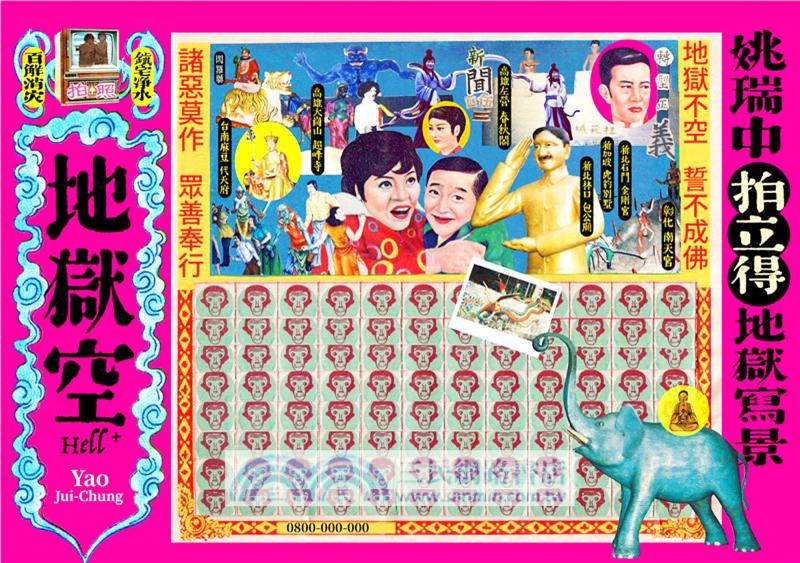

These dioramas of underworld torture can be found in numerous temples across Taiwan, most notably the bizarre animatronic scare-fest at Tainan’s Madou Daitian Temple (麻豆代天府) that’s touted as the bloodiest and most terrifying haunted house in the nation. For the past three years, Yao has been taking pictures of these displays, and on Sunday his latest photography collection, Hell+ (地獄空), was released to mark Ghost Festival.

So far, Yao hasn’t encountered anything too spine-chilling with this project — although he says he was haunted by three offended deities during his previous work Incarnation (巨神連線), where he made black-and-white large format prints of plus-size Buddhist and Taoist statues from more than 230 local temples. The effort earned him the top prize for visual arts during 2017’s Taishin Art Awards (台新藝術獎).

Photo courtesy of Yao Jui-chung

WHIMSICAL UNDERWORLD

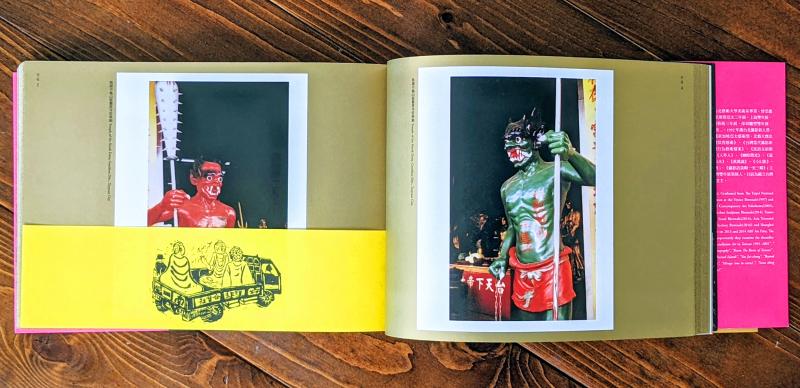

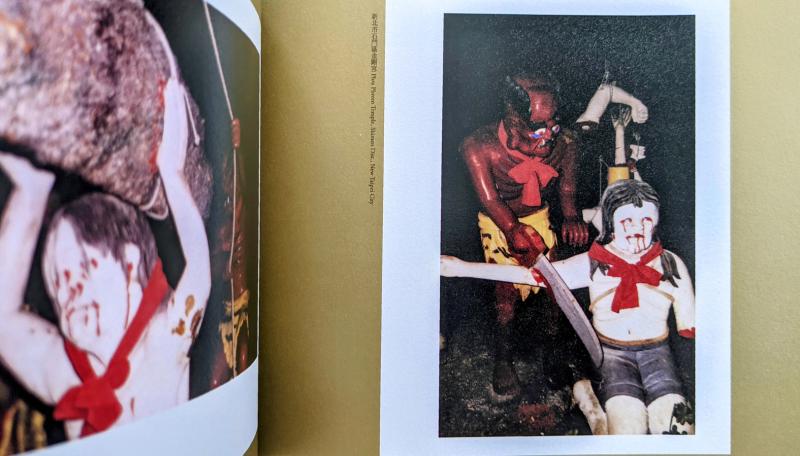

In contrast to the monumental, somber tone he used to document the gods, Yao went with Polaroids on gold paper for the scenes of hell. These displays are becoming less common, and the images mainly come from seven Taiwanese temples as well as the Haw Par Village theme park in Singapore. They are interspersed with related imagery Yao shot during his travels.

“I want to make heaven look like hell and hell look like heaven,” Yao says. “I used Polaroids because I wanted to portray hell as colorful and whimsical; the tones, focus and lighting are all slightly off as if one was getting a peek into the netherworld through a guanluoyin (“visiting hell”) ritual.”

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Yao found it difficult to sell the book to publishers due to its ominous nature, especially in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, and he quips that this is a “once-in-a-lifetime book.”

In addition to religious reservations, Yao says this sort of local folk art is often disregarded in the fine arts world as vulgar and kitschy, but he sees an “eerie beauty and quirky loveliness” in these aesthetics that are unique to Taiwan.

“I think these aesthetics are way more intriguing than a Michaelangelo,” Yao says. “Instead of portraying the ideal muscular body as they did in the West during the Renaissance, these figures look quite peculiar with their chubby bodies and short arms. The style is actually more relatable to the common person in comparison.”

Photo courtesy of Yao Jui-chung

CONVERSION TO BUDDHISM

Personally, however, they are part of his spiritual explorations after converting to Buddhism around 2017.

“The concept of hell is a phenomenon that arises from our desires, so the message of Hell+ is really about cultivating all good, purifying the mind and creating no evil,” Yao says. “If one can let go of all attachments, then there will no longer be a difference between heaven and hell because it doesn’t matter anymore.”

Photo courtesy of Yao Jui-chung

Yao hopes to complete projects on each of the Buddhist six realms of existence during his career. His previous work dealt more with the human realm as it highlighted social and political issues, but he started delving more into the afterlife starting from Incarnation.

Last year’s Taiwan Biennial at the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts, which Yao curated, was titled Sub Zoology (禽獸不如) and explored issues related to the animal realm.

In 2016, Yao says his mother went missing after the two had an argument. One night, a female bodhisattva came to him in a dream and told him to start taking photos of large Buddha statues. He started doing it immediately, and after a month or so his mother reappeared.

Photo courtesy of Yao Jui-chung

“I still don’t know where she went,” he says. “But I finished the project to fulfill my promise, and also started studying Buddhism because I wanted to know more about what these temples were about.”

The following year, Yao checked in to a hospital for an irregular heartbeat, and the doctor told him he needed an emergency operation to insert a stent in his heart or risk losing his life.

“I felt that death was so close to me, and I started thinking a lot about what is death and the afterlife,” he says. “I then realized that these statues we worship are only a projection of our fervent desires.”

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Giant religious statues are plentiful across Taiwan, but scenes of hell are not as common as many find them terrifying. For example, Yao says Fo Guang Shan Monastery only offers dioramas of heaven to the public — the staff there told him that there’s not much use in scaring people and it’s more effective to show them what paradise looks like.

Like most of his work, Yao doesn’t include human activity in his images.

“I always try to go when there are few visitors,” he says. “There are too many people shooting rituals and ceremonies already. I’m not looking at that, I’m more interested in the architecture, statues and scenery created by our desires.”

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

It’s the same concept as his decade-long, systematic documentation of Taiwan’s idle public property dubbed “mosquito halls” — expensive, highly-touted projects that ended up abandoned for various reasons.

“People give money to the government and they build mosquito halls, people give money to the temples and they build giant statues,” he says.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

With over 80 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of