At the peak of the whaling industry, in the late 1800s, North Atlantic right whales were slaughtered in their thousands. With each carcass hauled on to the deck, whalers were taking more than just bones and flesh out of the ocean. The slaughtered whales had unique memories of feeding grounds, hunting techniques and communication styles; knowledge acquired over centuries, passed down through the generations and shared between peers. The critically endangered whale clings on, but much of the species’ cultural knowledge is now extinct.

Whales are among the many animals known to be highly cultural, says Hal Whitehead, a marine biologist at Dalhousie University.

“Culture is what individuals learn from each other, so that a bunch of individuals behave in a similar way,” he says.

Photo: AP

North Atlantic right whales are no longer found in many of their ancestral feeding grounds. Whitehead suspects this may be because the cultural knowledge of these places was lost when populations were wiped out by whaling. This loss could spell trouble for the species if human activity degrades their remaining feeding grounds, making it hard for the whales to predict where good hunting is.

“The more possible feeding grounds they have, the more likely they are to find somewhere they can get the food they need,” he says.

Animal culture is not limited to the ocean. Birds, bees, naked mole-rats, fish and even fruit flies are among those that have been found to learn socially and create cultures. As the list grows, researchers are starting to understand animal culture as critical to many conservation efforts.

Photo: AFP

Whitehead was an early voice calling for animal culture to be taken seriously in conservation. This is because cultural diversity gives a species a larger behavioral toolkit when facing new challenges, he argues.

“We recognize this with humans, that the diversity of our cultures is a strength,” he says.

Whitehead is a member of the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, a body that decides which species are endangered.

“The most difficult thing we do is to decide how to divide a population of a species up,” he says.

With caribou, for example, plains caribou are doing better than mountain caribou.

“Do we assess the mountain caribou differently from the others?” Whitehead asks.

Typically, this decision is made by assessing how genetically different the groups are. “One of the things I’ve been pushing is the idea that cultural information is also important.”

Conservation efforts aim to maintain a species’ diversity, as diversity aids survival. Species diversity can be “what it does, how it looks, its physiology and so on”, says Whitehead. “A lot [of the diversity] is genetically determined but some of it is culturally determined.”

The behaviors a population displays can have a significant impact on the environment they live in.

“If we lost all the mountain caribou, it might change the ecology of a bunch of mountain tops,” Whitehead says.

Whitehead’s research into whale culture provided a lightbulb moment for Philippa Brakes, a research fellow at Whale and Dolphin Conservation. Brakes, a PhD student at the University of Exeter, published a paper with colleagues in April, which argues that conservation efforts should consider how culture affects reproduction, dispersal and survivorship.

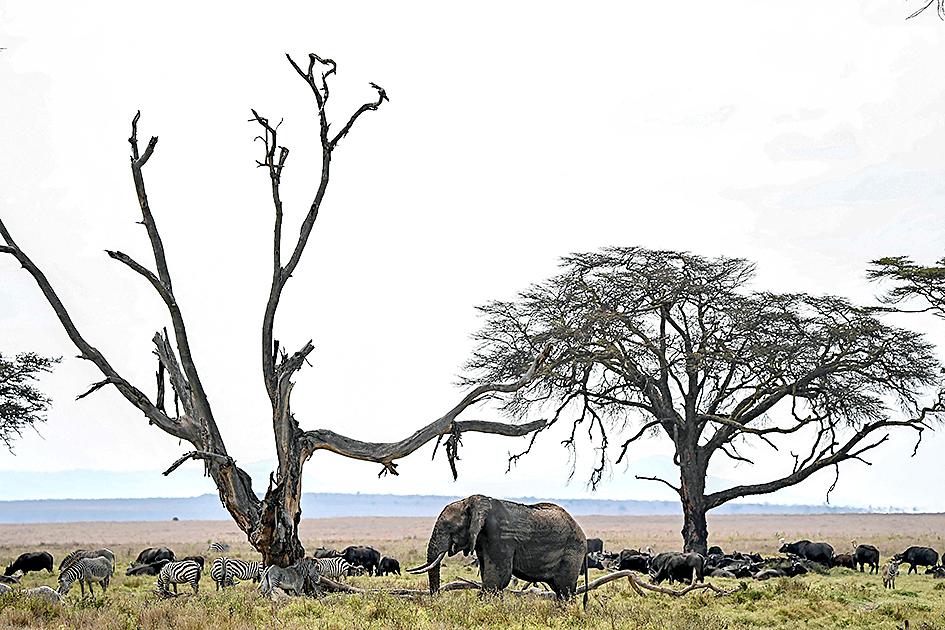

Understanding who holds cultural knowledge in a population can be key, says Brakes, who cites African elephant herds as an example.

“The age of the matriarch in the herd has a significant [positive] influence on the fertility rate of the younger females,” she says.

However, when a population has lost its cultural knowledge, there may be circumstances where it can be reignited.

If a human was removed from their home, stripped of everything they had ever learned from others and then plonked back, they would not survive long without support. The same seems to be true for golden lion tamarins, a small monkey from Brazil.

By the early 1970s, habitat destruction and the pet trade had reduced the golden lion tamarin population to as few as 200 individuals. Captive breeding, overseen by 43 institutions in eight countries, increased their numbers to the point that conservationists were able to reintroduce the tamarins into the wild from 1984. But initially, the reintroduced tamarins had a low survival rate, with problems with adaptation to the new environment causing the majority of losses. High casualties are typical of such efforts, says Brakes.

So the tamarin researchers developed an intensive post-release program, including supplementary feeding and the provision of nest sites, giving the monkeys time to learn necessary survival skills for the jungle. This helping hand doubled survival rates, which was a good start. However, it was not until the next generation that the species began to thrive.

“By giving them the opportunity to learn individually in the wild and share that knowledge, the next generation of tamarins had a survival rate of 70 percent, which is just amazing,” says Brakes.

The intensive conservation efforts paid off, and in 2003 the golden lion tamarin was upgraded from critically endangered to endangered.

Although this research is promising, animal cultures are becoming extinct faster than they are being reignited, says Brakes.

“We are just starting to understand what culture is in other species and just starting to develop methods for measuring and analyzing culture, as we are seeing it disappear before our eyes.”

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the