If All Souls is one of the most inordinately beautiful colleges in Oxford, it’s also one of the oddest and most rarefied. Famously, it has no student body. Each year, however, a small number of recent graduates who would like to become so-called prize fellows may apply to take a famously difficult and inscrutable exam during which, as a tour guide I followed earlier put it, they must “write an essay on a single word, like coconut.”

As my eavesdropping also revealed, TE Lawrence, aka: Lawrence of Arabia, passed this exam, but Harold Wilson failed it.

In her lovely, wood-panelled room in All Souls — its current tenant wears Adidas sneakers and likes a good martini, but it still makes me think of patched corduroy and sherry — Amia Srinivasan laughs heartily.

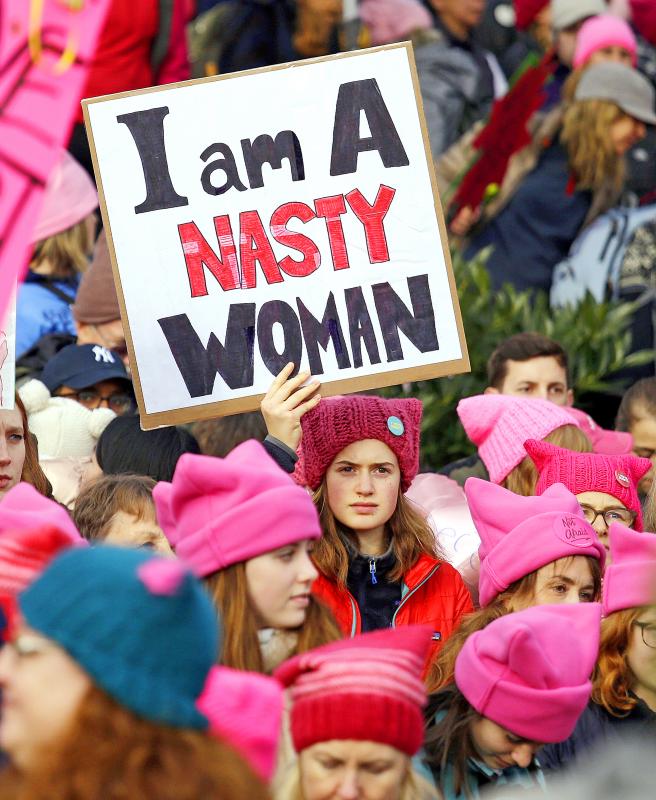

Photo: AP

“Right,” she says. “Those guides. They always come up with things like: everyone here is a priest, or everyone is a man. Or they tell people: ‘Stephen Hawking is in there right now.’ At least the exam thing is sort of true.”

Having taken it successfully herself in 2009 — she had to write around the word “reproduction” — Srinivasan was a prize fellow at the college until 2016, when she became a lecturer at UCL (the one-word riff component was abandoned the following year). Now, though, she’s back. Last January, she took her up her post as the Chichele professor of social and political theory at All Souls, a job once held by Isaiah Berlin. She is both the first woman, and the first person of color, to hold it. At just 36, she is also its youngest ever incumbent.

THE DON OF SEX

Photo: AP

Oxford is notoriously stodgy and unchanging; this morning, still eerily quiet thanks to the ongoing absence of tourists, it feels more than ever like a film set. But while the All Souls Web site (the college isn’t that rarefied) does indeed soberly include “epistemology and philosophical methodology” among her several research interests, Srinivasan’s reputation outside the university is at this point built on rather more racy matters.

Thanks to her much-praised new book, The Right to Sex, a collection of essays that takes on such thorny subjects as pornography, student-teacher relationships and the rise of the incel “community,” the media has decreed her to be philosophy’s hottest property.

The current issue of Vogue describes her, with utmost breathlessness, as “a star” who will change the way we think of sexual consent, while in Prospect, a magazine you might expect to be a bit more sanguine about these things, she is depicted as the single-handed savior of analytic philosophy, at least when it comes to what people do when they’re naked.

“Sex is [now] where the action is,” writes her eager young interviewer, ahead of his “tutorial” with her.

Actually, it must be thrilling to be taught by Srinivasan. I bet the air crackles. But I’m also interested in what her fellow dons make of her. If this were a David Lodge campus novel, the excitement, not to mention the envy, would be throbbingly palpable at dinner.

“Well, David Lodge had a lot right,” she says, laughing again. “I haven’t been into dinner since the book has really been a thing, but I’m sure there will be… conversations.”

I shouldn’t tease, though: she doesn’t regard Oxford as parochial — on the inside, she insists, it feels very “alive” — and it’s only thanks to the university, after all, that she is able to work on such vexed topics in the first place.

“I’ve never thought about the weirdness of sex as a subject,” she says. “To me, it’s just something that is politically very, very serious. If you’re steeped in the history of feminist thought, it doesn’t occur to you to think that such discussions wouldn’t have a rightful place here.”

Are her students as open-minded as she is? We hear a lot about no-platforming and trigger warnings.

“... [Y]es, my students seem to feel very free, and come consistently with a broad range of political perspectives. We’re in the middle of a new set of culture wars; there are questions about how you balance students’ need to enter the classroom on equal terms when it comes to respect with the challenging, even threatening, nature of education. But the headline conversations in the mainstream media and on Twitter about snowflakes are reductive and ideologically motivated.”

SEX AS POLITICS

The Right to Sex grew out of “Does anyone have the right to sex?” an essay that Srinivasan published in the London Review of Books in 2018: a provocative, highly intellectual bit of writing that, in context, rather stood out for its casual (and yet, not casual at all) use of the word “fuckability,” as well as for the attention it paid to the woes of Asian men on Grindr. This essay having “resonated” with readers, a publisher suggested to her that she might extend it into a book. Was she ready to do this? Yes, she was.

“I had a series of preoccupations around sex as a political phenomenon,” she says. “I’d wanted to write the essay Talking to My Students About Porn specifically because of my surprise at how students responded to being taught the porn debates [of the late 1970s], and On Not Sleeping With Your Students was also born out of my own experiences, chiefly, the transition from student to teacher. In both cases, I wondered: how do we get a better articulation of what is problematic here?”

Srinivasan teaches an undergraduate course in feminist theory — among a teetering pile by the window, I can see several of the books I read myself as a dungaree-clad young woman — and in such a class, an examination of “the porn question” is, she asserts, more or less mandatory. At first, though, her heart wasn’t really in it. She imagined that her 21st-century students would find 70s feminists such as Andrea Dworkin and Catharine MacKinnon prudish and old-fashioned.

“The surprise was that they didn’t,” she says.

Her students, she grasped, belong to the first generation to have come of age sexually in a world in which porn is ubiquitous. They have a heightened sense of its power; many of them don’t only believe that it depicts the subordination of women, but that it makes such subordination real.

“This did feel like a radical thought,” she says. “I was shocked that they were instinctively drawn to anti-porn feminism, even as they know that the Internet cannot be contained.”

In her essay, she warns of the way porn has limited the sexual imagination; it has been transformed, she writes, into a “mimesis machine, incapable of generating its own novelty.”

But she will not advocate for censorship, seemingly believing that, in practice, it would likely end up as a cover for attacking sexual minorities. To prohibit marginal sex, she asserts, is to reinforce the “hegemony of mainstream sexuality,” and with it mainstream misogyny.

LET’S TALK ABOUT PORN

Talking to My Students About Porn is pretty representative of the essays in The Right to Sex. For one thing, it’s deeply engaged with poor old second wave feminism, a movement now repudiated (or, worse, simply ignored) by many younger women, who regard it as having been fatally privileged (ie, white and middle-class).

“There is a desire on the part of people to distance themselves from that era,” she says. “But my students find these texts — by people like Robin Morgan and Shulamith Firestone — riveting and thrilling, in the same way that they might find Plato’s Republic riveting and thrilling.”

For another, there’s the way that the essay is (mostly) unwilling to deal in absolutes.

“The broad methodological orientation of the books is an unswerving embrace of ambivalence,” she tells me. Sex, she agrees, may well be two things at once. It may, for instance, not feel right even if it isn’t, legally speaking, wrong — which is what makes it so fiendishly difficult to police.

But this is not to say that Srinivasan doesn’t occasionally embrace what some may regard as the un-embraceable. There were moments when she worried she was paying, in the essay called The Right to Sex, too much attention to the likes of Elliot Rodger, the 22-year-old college dropout who, in 2014, became the world’s most famous incel, or “involuntary celibate” — Rodger murdered six people and injured 14 others in Santa Barbara before shooting himself in the head — and some readers will struggle with her notion that the exhortation to “believe women” has limits.

(“For many women of color,” she writes, “the mainstream feminist injunction ‘Believe Women’ and its online correlate #IBelieveHer raise more questions than they settle. Whom are we to believe, the white woman who says she was raped, or the black or brown woman who insists that her son is being set up?”)

In the essay about student-teacher relationships, she writes of Jane Gallop, an American academic and feminist who was accused of the sexual harassment of female students (Gallop acknowledged relationships with these women, but denied harassment).

“Some people think I probably shouldn’t have talked about it,” says Srinivasan. “They might regard her as a predator. But the book she wrote about her experiences is a kind of feminist text, and there is so much to be learned from the performance of it, from its silences and elisions.” (I’ve read it, too, and I think she’s right about this.)

GENDER AND SEXUALITY

Amia Srinivasan was born to Indian parents in Bahrain, and grew up in Taiwan, New Jersey, New York, Singapore and London (her father works in finance, her mother is a dancer and choreographer). She didn’t become interested in feminism until after her first degree at Yale, when a friend gave her Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex (she came to Oxford initially as a Rhodes scholar, and later did her DPhil here).

“At Yale, I was hardly taught by any women,” she says. The Right to Sex was written over the course of two summers in California — she would get up at 6am to surf before settling down to work — but you would never know it; while the book is often tart, it’s not exactly sunny.

Srinivasan believes that women’s hard-won rights are “intensely precarious… the right is in the ascendant, and though its rhetoric is an expression of its weakness, the left simply doesn’t know how to take power.”

Furthermore, she despairs of the relationship many feminists now have to state power.

“In the late 60s, women were rethinking everything. There was this radical exuberance. But over two decades, those energies have been subverted and redirected to politically problematic ends. Suddenly, it’s more cops on the street, more men of color in prison, foreign wars… the carceral state.”

When feminists call — as they did after the murder of Sarah Everard in London last March — for “action” on male violence, they need, or so she believes, better to understand what that might involve in practice; what groups they will end up working against, as well as for. Her feminism is, in other words, the polar opposite of that espoused by writers who go on about the individual, about empowerment and self-kindness.

The conversation around sexuality and gender is, disappointingly in her view, moving far faster than that around social class. Why does she think this is?

“Talking about class is profoundly threatening,” she says. “It’s easier to co-opt radical discourses around racial and gender oppression than it is around class oppression — though the ascendancy of Trump had a lot to do with the right’s co-option of a certain kind of class critique.”

Could it be moving too fast?

“It’s easy to get nostalgic. One’s own safety… no one is ever fully and truly safe. We’ve got to separate political developments that treat certain groups unfairly from the fantasy of the perfectly safe political space.”

Feminism cannot, she believes, indulge the illusion that interests always converge, that its plans will have no unexpected, undesirable consequences, and she is impatient with those who are, say, concerned by the thought of transgender women in women’s prisons.

“If you were really worried about prisons, you would be demonstrating outside Yarl’s Wood [the immigration removal center],” she says, with some irritation. “This movement against any incursion into our sense of bodily and psychic integrity: it’s a fantasy that rules a lot of reactionary politics, right?”

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,