July 26 to Aug. 1

Five hours after they ventured inland, the European expedition party returned to the St Peter and St Paul with five Taiwanese prisoners — two of them seriously wounded. Three party members were struck by arrows. What’s believed to be the first European landing on the nation’s east coast 250 years ago obviously did not go well.

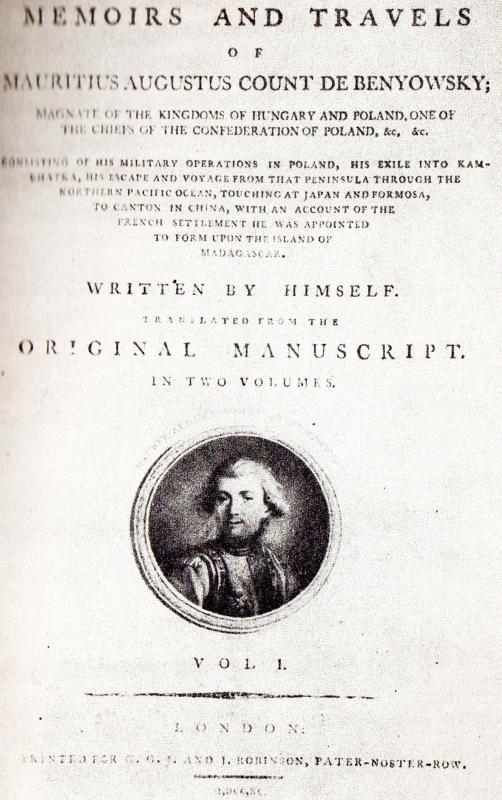

According to the 1790 English translation of the Memoirs and Travels of Mauritius Augustus Count de [Benovsky], the 18-person group found a few people on the shore and asked for food. They were taken to a village and fed “boiled rice with roasted pork and a quantity of lemons and oranges,”and they offered a few knives in return.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

As the party made its way back to the ship to deliver the news, they were suddenly hit by a shower of arrows. The Europeans fired back immediately, mowing down about a half-dozen attackers. They were ambushed again as they neared the ship, this time defeating 60 warriors and capturing five of them.

“Upon this information, I would have quitted the place, as I was not desirous of exposing myself to a war with the natives,” Benovsky writes. “But my associates insisted on entering the harbor. I found it impossible to calm their fury, and for that reason, at last consented.”

The Slovakia-born Benovsky ended up staying in what’s believed to be today’s Suao (蘇澳) for 16 blood-soaked days, where his crew ended up helping a local “prince” win a massive battle against their pro-Chinese enemies.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

While Benovsky is considered somewhat of a national hero in Poland, Slovakia and Hungary, it’s generally agreed that his tales were greatly exaggerated and full of fabrications, and should be taken with a huge grain of salt.

WHITEWASHING VIOLENCE

Benovsky’s brief visit is often brought up when discussing the relations between Slovakia and Taiwan. The two democratic nations enjoy strong ties — most recently, Slovakia pledged to donate 10,000 COVID-19 vaccines to Taiwan in return of the 700,000 face masks Taiwan provided last year.

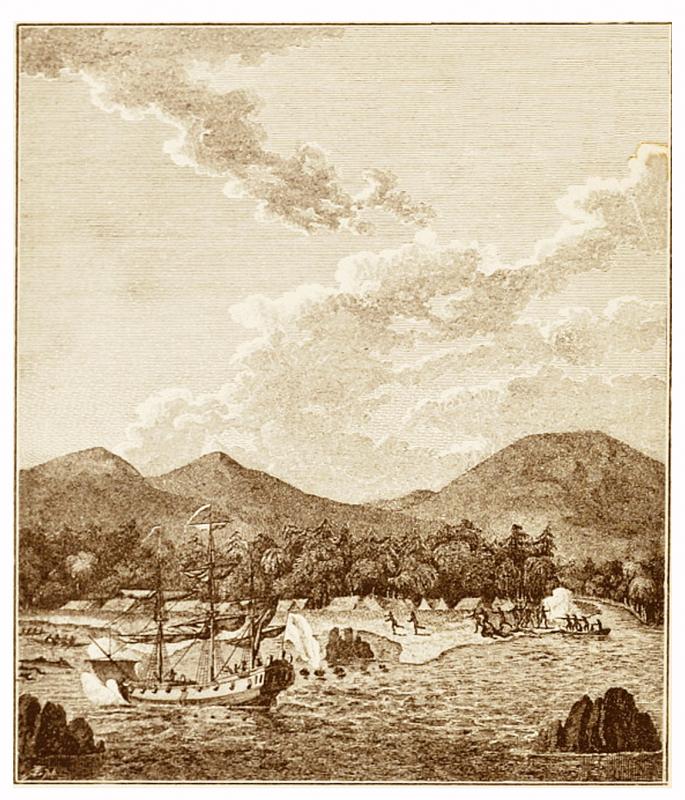

An illustration of the clash between locals by Count Moric Benovsky’s crew in 1771, found in Benovsky’s memoirs.

Last Saturday, the Yilan County Government announced its plans for a special exhibition to commemorate the 250th anniversary of Benovsky’s landing. Titled “1771: Count Benovsky in Yilan,” it will open on May 13 next year at the Lanyang Museum. The office also announced plans of erecting a statue near the spot where Benovsky came ashore.

There are some issues with the announcement, however, as it’s simply untrue to state that Benovsky established a “point of contact” between the two countries and that his arrival marks 250 years of “friendship” between Slovakia and Yilan. His encounters with the local Aborigines were mostly violent and led to thousands of deaths, and history should not be whitewashed to bolster current relations.

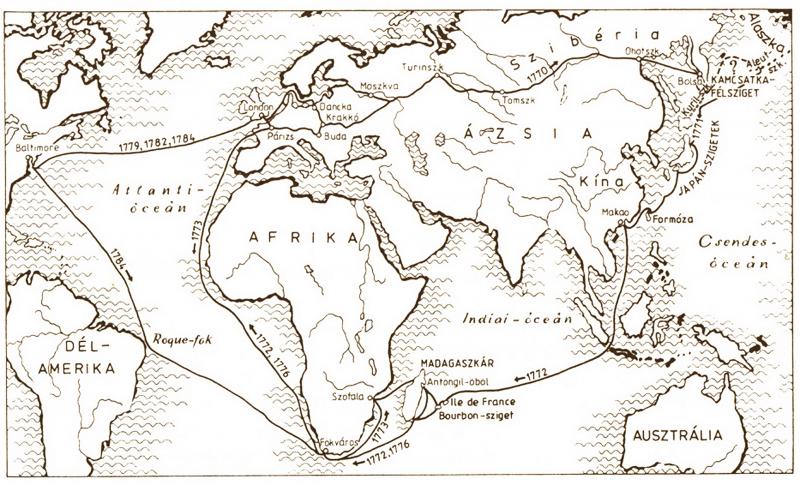

Benovsky was reportedly born in Vrbove, a small town in today’s Trnava region of Slovakia in 1746. Slovakia did not exist then, it was part of the Kingdom of Hungary. He was captured by the Russians while fighting for the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in today’s Ukraine, and eventually sent to far east Siberia as a prisoner-of-war.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

He managed to escape with a group of about 70 people and made his way south, passing through Japan and the Ryukyu Islands. They decided to make a pit stop in Formosa before heading on to Macau, where they would seek passage back to Europe.

MORE FIGHTING

A day after the first skirmish, a larger landing party rowed ashore and were met by about 50 locals who appeared unarmed and submissive. Upon this sight, 22 Europeans decided to head to the village despite the leader’s objections — and soon, another fight broke out. This time, 200 locals were killed with 11 Europeans injured.

Benovsky and his crew left the area, and were guided by locals into a “beautiful harbor” to the north. There, he meets Don Hieronemo Pacheco, a Spaniard from Manila who had been living with the Aborigines in Taiwan for seven or eight years. These locals were very grateful toward Benovsky, as the people his crew killed earlier were their enemies.

Pacheco explains to Benovsky that the part of the western side of the island was “subject to the Chinese,” but the rest was either independent or inhabited by Aborigines.

“He assured me, that with very little assistance, he thought it practicable to conquer the island and drive out the Chinese,” Benovsky writes.

By the third day, Benovsky was referring to the harbor as “Port Maurice” — named after himself. Conflict erupted again as a party sent to fetch fresh water clashed with Aborigines, and three Europeans were killed.

Bent on revenge, the crew executed their surviving three prisoners, then attacked and slaughtered a boatful of enemies. Benovsky pleaded for them to stop then, but to no avail. At the end of the battle, they counted 1,156 dead Aborigines and 640 captives.

They were then visited by a prince named Huapo, who was convinced that Benovsky “was the person whose coming was announced by the prophets who had foretold that a stranger should arrive with strong men who would deliver Formosa from the Chinese yoke.”

With Benovsky’s Western arms, Huapo was able to defeat his pro-Chinese foes. Huapo showered Benovsky’s crew with gold and other riches, treating them so well that some companions tried to persuade him to stay — but Benovsky wanted to go home and see his wife and newborn son. He added that the best way was to report the findings to the royals in Europe and obtain better ships and supplies before returning.

DEBUNKING BENOVSKY

Countless experts have questioned Benovsky’s exploits over the years, but Ian Inkster’s “Orientat Enlightenment: The Problematic Military Claims of Count Maurice Auguste Conte de Benyowsky in Formosa during 1771” looks specifically at the Taiwan section.

The population in Benovskly’s account was inconsistent to estimates during those times — that stretch of coast likely had 6,000 and 10,000 inhabitants, but somehow the prince could muster 25,000 warriors to fight against 12,000 enemies. Another problem is the abundance of horses — Huapo commanded nearly 100 horsemen and had 68 to spare for Benvosky to use during the fight.

While the Dutch introduced some horses to southeastern Taiwan during their rule, it is highly unlikely that Aborigines on the northeast coast managed to acquire so many and train them for large-scale warfare.

Despite all this adversity, Benovsy still wanted to build a colony in Taiwan, which he said was the “finest and richest island of the known world.” A few days before his departure, he sat down and made detailed notes on the people and resources of the island and what he would need to colonize it.

Benovsky never returned to Taiwan, however. Upon returning to France, he managed to put together two expeditions to colonize Madagascar. He seemed have encountered limited success and was killed in 1786.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the