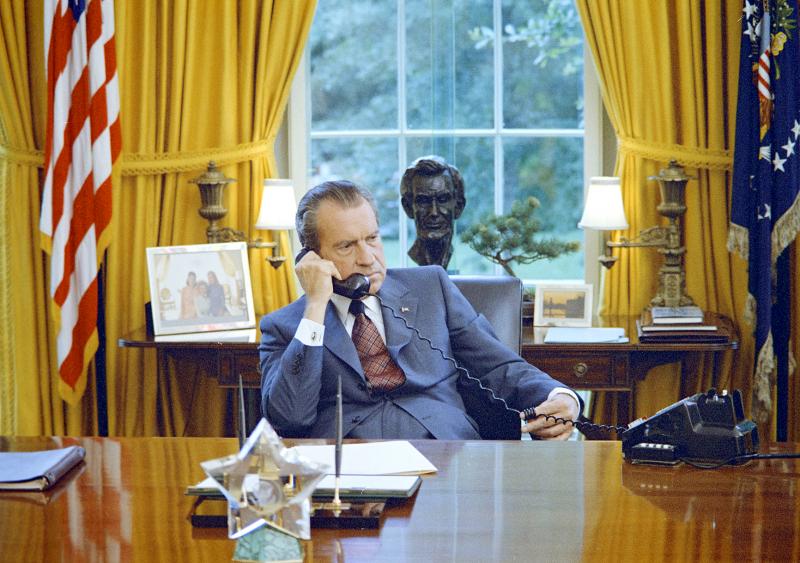

US president Richard Nixon had a lot on his mind in the spring of 1971. The Watergate break-in that would ultimately bring down his presidency was more than a year away, but he had a full foreign policy plate with an unpopular war in Vietnam, tensions in the Middle-East and stalled efforts to bring Moscow to the table for talks on limiting nuclear arms.

One other foreign policy challenge, not then publicly known, was the tantalizing prospect of rapprochement with communist China after two decades of estrangement. Nixon and his national security advisor, Henry Kissinger, both believed a breakthrough with “Red China” would increase their leverage in peace talks with the North Vietnamese and arms talks with Moscow.

Something else weighed heavily on Nixon’s mind at that time. Opening up dialog with Beijing might come at the expense of the Republic of China (ROC) on Taiwan. Nixon, who had based his political career on being a staunch opponent of Communism, was a personal friend of the-then 83-year-old Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) leader Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石), whom Nixon fondly referred to as “the old man.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

‘WHAT’S BEST FOR US’

In a phone call with Kissinger on the evening of April 14 — the same day TV networks reported on the US ping pong team being invited to China — Nixon expressed his concern over Taiwan’s future.

“The Taiwan thing, that’s sort of worrisome, I don’t know if there’s a damn thing we can do about it, is there?” he asked of Kissinger, who replied: “It’s a tragedy that it had to happen to Chiang at the end of his life, but we have to be cold about it.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Nixon concurred, adding: “We have to do what’s best for us.”

On July 17, two days after announcing he would make an historic “journey for peace” to Beijing the following year, Taiwan was again on his mind.

“[The president] also brooded some again today, as he does frequently, about the question of how Taiwan can survive now, and that obviously really concerns him,” White House chief of staff H.R. (Bob) Haldeman noted in his diary entry that day.

During his 17 hours of secret meetings with Chinese Premier Chou Enlai (周恩來) in Beijing earlier that month, Kissinger pushed back when Chou tried to link US recognition that Taiwan was “a province of China” as a precondition of Nixon’s visit. However, Kissinger seemed to acquiesce on Chou’s insistence that the visit should set recognition as the “ultimate direction” of US policy.

In his July 14 memo to Nixon on the Chou meeting, Kissinger wrote: “He accepted my position that some time would be required, ie, well into your second term.”

The implication was that, in Nixon’s second term, Taiwan would be abandoned. Haldeman said as much in his July 17 diary entry.

“No promises have been made and no commitments have been made to the Chinese that have to be delivered prior to 1972. But after that, it’s inevitable that Taiwan is going to have to become a province of China or something of that sort. And it does pose a problem especially since the President has been an old China hand from way back — a free China hand, that is,” Haldeman said.

WATERGATE SCANDAL

Although Nixon won the 1972 election in a landslide, the unraveling Watergate scandal would soon consume his presidency and he resigned on Aug. 9, 1974.

In Beijing, communist Chinese leader Mao Zedong (毛澤東) was doing some brooding of his own. Kissinger, who met Mao again on Nov. 12, 1973, noted the chairman’s bafflement at how a “minor incident” like Watergate could cause the “destruction of a strong president.”

“Why is it in your country, you are always so obsessed with that nonsensical Watergate issue? Anyway, we are not happy about it,” Mao said, in slurred speech that was interpreted by his translator.

In the same meeting, Mao admitted Beijing’s relationship with Taiwan was “quite complex,” adding a comment that would have made the US delegation very uncomfortable: He did not believe in a peaceful transition.

“They are a bunch of counter revolutionaries. How could they cooperate with us? I say that we can do without Taiwan for the time being, and let it come after 100 years,” Mao was quoted saying in the official Department of State transcript of the meeting.

Kissinger, who by then was also serving as Nixon’s Secretary of State, replied that the US wanted diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic but that the “current domestic situation” — a probable reference to Watergate, as well as the strong support for Taiwan in Congress — meant that the US could not “immediately sever relations with Taiwan.”

Subsequent high level meetings between US and Chinese leaders would see the same “excuse” given as to why the current administration could not immediately sever relations with Taiwan.

In a meeting with Chinese Vice Premier Deng Xiaoping (鄧小平) on Dec. 4, 1975, Nixon’s successor, president Gerald Ford, said: “We are very grateful that you are understanding of the domestic political situation in the United States.”

When Deng repeated Mao’s earlier assertion that Beijing did not believe in a peaceful transition, and noted Kissinger’s repeated references to Mao’s 100 year time frame, Ford said to laughter: “You can argue that 100 years is a peaceful transition.”

Prior to president Ford’s China visit, Kissinger had met with the Chinese leadership on Oct. 21 that year, accompanied by Ambassador George H. W. Bush and State Department official Winston Lord, who described the meeting as “disturbing,” citing the Chinese perception that the US had become “unreliable” and was a “fading strategic power in the face of Soviet advance.”

Lord’s memo on the meeting, which was handed to president Ford by Kissinger, made the following recommendation on Taiwan: “For now it is better to have the US keep the island under control rather than having it go independent or toward Moscow or Tokyo. The Chinese can wait patiently until the time is ripe, but then they will have to use force ... the US should not ask for peaceful assurances, but it can take its time letting Taiwan go.”

It would be Jan. 1, 1979 before the US would eventually cut diplomatic ties with Taiwan in favor of Beijing, a unilateral move taken by then-president Jimmy Carter, but he too could not ignore the Taiwan-friendly US Congress, which passed the Taiwan Relations Act that ensured the US would provide Taipei with defensive weapons, a move that infuriated Beijing.

Carter only served one term and his successor, Ronald Reagan, was a staunch supporter of Taiwan. During the 1980 election campaign Reagan even threatened to reverse Carter’s decision to cut ties with Taipei, but once in the White House Reagan stuck to the “one China” policy.

In the intervening decades, Taiwan was able to build what has become known as its “silicon shield” — the state-of-the-art semiconductor industry that supplies more than half of the world’s advanced chips — essentially protecting it from the threat of a Chinese military attack.

But the break-in at Washington’s Watergate hotel on June 17, 1972 may well have saved Taiwan from being handed over to China by Kissinger and Nixon.

Craig Addison is writer/producer of Nixon’s China Choice, a podcast docudrama (nixonschinachoice.podbean.com) that tells the behind-the-scenes story of Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger’s secret diplomacy with China in 1971, and how Taiwan was a pawn in the big game.

When nature calls, Masana Izawa has followed the same routine for more than 50 years: heading out to the woods in Japan, dropping his pants and doing as bears do. “We survive by eating other living things. But you can give faeces back to nature so that organisms in the soil can decompose them,” the 74-year-old said. “This means you are giving life back. What could be a more sublime act?” “Fundo-shi” (“poop-soil master”) Izawa is something of a celebrity in Japan, publishing books, delivering lectures and appearing in a documentary. People flock to his “Poopland” and centuries-old wooden “Fundo-an” (“poop-soil house”) in

Jan 13 to Jan 19 Yang Jen-huang (楊仁煌) recalls being slapped by his father when he asked about their Sakizaya heritage, telling him to never mention it otherwise they’ll be killed. “Only then did I start learning about the Karewan Incident,” he tells Mayaw Kilang in “The social culture and ethnic identification of the Sakizaya” (撒奇萊雅族的社會文化與民族認定). “Many of our elders are reluctant to call themselves Sakizaya, and are accustomed to living in Amis (Pangcah) society. Therefore, it’s up to the younger generation to push for official recognition, because there’s still a taboo with the older people.” Although the Sakizaya became Taiwan’s 13th

For anyone on board the train looking out the window, it must have been a strange sight. The same foreigner stood outside waving at them four different times within ten minutes, three times on the left and once on the right, his face getting redder and sweatier each time. At this unique location, it’s actually possible to beat the train up the mountain on foot, though only with extreme effort. For the average hiker, the Dulishan Trail is still a great place to get some exercise and see the train — at least once — as it makes its way

Earlier this month, a Hong Kong ship, Shunxin-39, was identified as the ship that had cut telecom cables on the seabed north of Keelung. The ship, owned out of Hong Kong and variously described as registered in Cameroon (as Shunxin-39) and Tanzania (as Xinshun-39), was originally People’s Republic of China (PRC)-flagged, but changed registries in 2024, according to Maritime Executive magazine. The Financial Times published tracking data for the ship showing it crossing a number of undersea cables off northern Taiwan over the course of several days. The intent was clear. Shunxin-39, which according to the Taiwan Coast Guard was crewed