July 12 to July 18

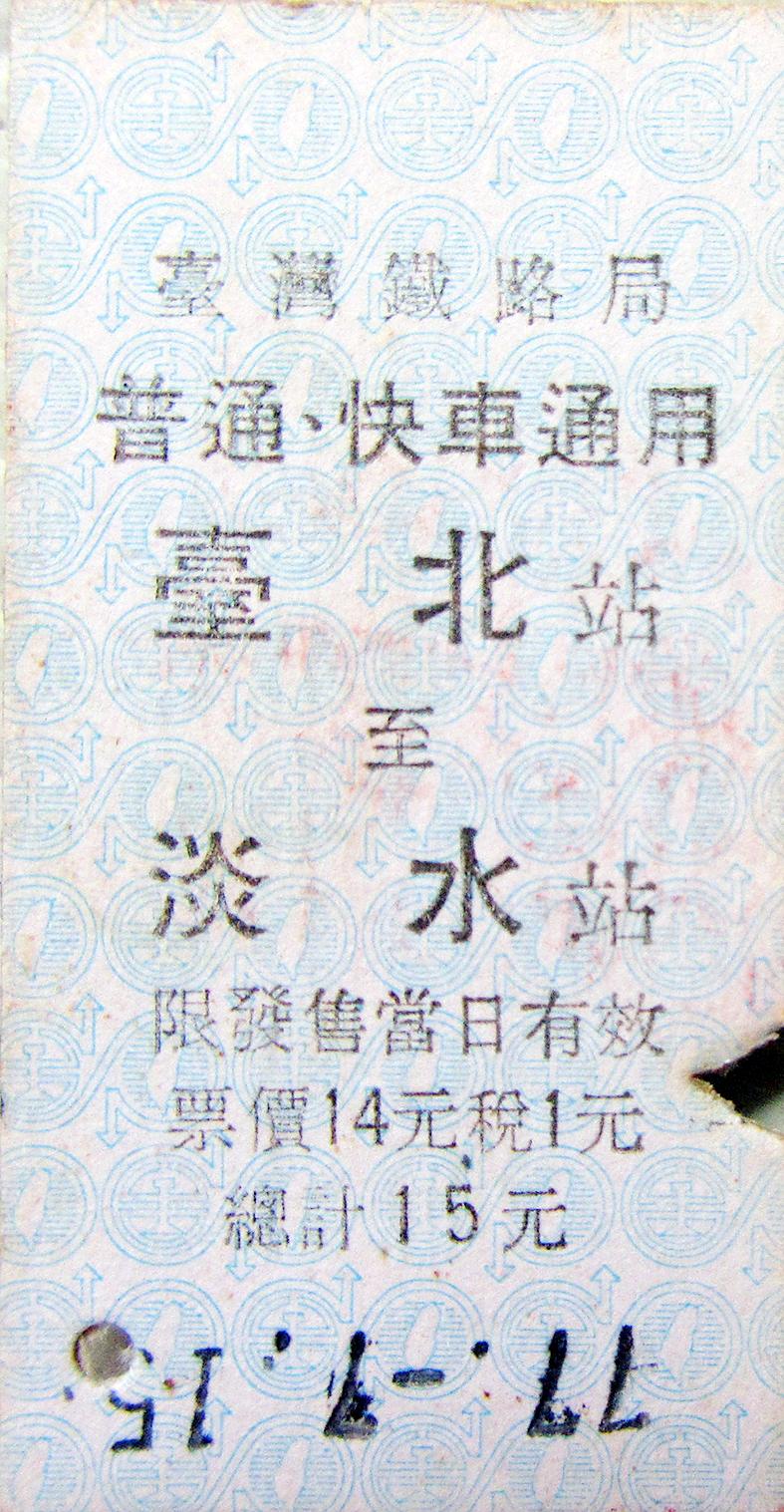

Despite being 10 cars longer than usual, the Tamsui-bound train was packed to the brim on the morning of July 16, 1988. Passengers leaned out the window to soak in the scenery, and the train arrived at the final destination to a cheering crowd setting off firecrackers.

This journey was the Taipei-Tamsui line’s final passenger run after 87 years of operation. The official final run actually took place the previous night, but the event was so popular that the Taiwan Railway Administration allowed one more trip for those who missed it.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Freight service would carry on for another two months before the tracks were removed. The estimated 22,000 daily commuters who relied on the train had to seek other means of public transportation until the Tamsui MRT line opened in March 1997. This MRT route closely followed the old rail tracks.

Inaugurated by the Japanese on Aug. 25, 1901, the Taipei-Tamsui railway was built using tracks from the Qing-era Keelung-Taipei line. That day was a significant one in Taiwan’s railway history, as it saw the opening of both the second-generation Taipei Station and Taipei-Taoyuan line.

The Taipei-Tamsui railway diminished in importance over the decades as automobile travel became more common and convenient. Its fate was sealed in 1986 when the Council for Economic Planning And Development formally approved the MRT project, which even it its early stages involved tearing down the railroad.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

A NEW BRANCH

The Qing had started building a north-south railroad during the final years of its rule; by the time the Japanese arrived in 1895, it stretched from Keelung to Hsinchu.

However, due to years of mismanagement and sabotage by retreating Qing troops, the railroad was in pretty bad shape. The new rulers spent the first few years rebuilding and rerouting the Keelung-Taipei section, and by 1899 they were ready to continue pushing south.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Tamsui branch line was conceived in response to sediment buildup in the Tamsui river, and to better transport supplies from the port to support the main line’s southward expansion. A significant portion of the tracks were repurposed from uprooted sections of the Qing-era route due to lack of resources.

The first iteration of the line had only five stops: Taihoku (today’s Taipei), Shirin (Shilin), Maruyama (Yuanshan), Hokuto (Beitou) and Tansui (Tamsui). Kanto (Guandu) was added shortly afterward.

The southern terminus was moved several times — in 1903 to Daitotei (Dadaocheng), in 1915 to Hokumon (Beimen) and in 1924 to Taipei Rear Station, a wooden structure that mysteriously burnt down in 1989.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Five more stations opened in 1915, including Miyanoshita (literally “under the shrine”), which was set at the foot of the path leading to the Taiwan Grand Shrine, the colony’s highest-ranking Shinto place of worship. The shrine was built in 1901 to honor Prince Kitashirakawa Yoshihisa, who died during the 1895 war between the colonizers and resisting local militias. Much effort was made to improve access to the shrine, parts of today’s Zhongshan N Road and Zhongshan Bridge (then called the Meiji Bridge) were built for this purpose.

The shrine was damaged during World War II, and after the war much of its materials were removed for projects elsewhere, including the Zushih Temple (清水祖師廟) in New Taipei City’s Sansia District (三峽). The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) renamed Miyanoshita Station “Jiantan” after the mountain the shrine sat on, and built the Grand Hotel in its place in 1952. Jiantan Station was discontinued the following year, but the MRT station in the area took on this name four decades later.

MANY CHANGES

Another notable addition to the Taipei-Tamsui line was the branch from Beitou to the hot springs haven of Xinbeitou in 1916. It was Taiwan’s first railroad built for tourism purposes, and led to a massive boon in the area. The tracks were removed in 1945 and reportedly used as anti-landing barricades along the Tamsui shore to prevent an Allied invasion. It was rebuilt the following year.

After the discontinuation of the railway in 1988, the Taipei City Government sold the historic Xinbeitou Station to the now-defunct Taiwan Folk Village (台灣民俗村) theme park in Changhua for NT$1. Locals launched a campaign to reclaim the station in the late 1990s, and they finally got their wish on April 1, 2017, the 101st birthday of the structure.

A temporary station was added in the Fuxinggang area (復興崗) for a week in 1954 to accommodate that year’s Taiwan Provincial Games (today’s National Games). Riders received commemorative tickets.

In 1966, a single-lane, muddy road between Taipei and Tamsui was widened and named Xiandu Road (仙渡路), providing an alternative means for people to traverse the two locales. It was expanded again in 1972 and given the current name of Dadu Road (大度路). Coupled with the advent of private car ownership, this road began to eat into ridership on the Taipei-Tamsui railway.

By the 1980s, the government determined it viable to remove the railway to make way for the MRT. Dadu Road was upgraded again in 1984, and in May 1986 its speed limit was raised to 70km per hour. The railway’s demolition was approved that same year.

The Tamsui-Taipei MRT line took on all of the railway’s station’ names except for Wangjia Temple (王家廟), which was located between today’s Qilian and Qiyan stations. Curiously, there was never a Wangjia Temple in that area. The station was meant to be named after the nearby Chengan Temple (鎮安宮, also known as Wangye Temple), but it was inexplicably misnamed due to a clerical error.

The MRT line went through many adjustments over the next decade, and between 1999 and 2012 there were two lines running on the tracks, Tamsui-Xindian and Beitou-Nanshijiao. It assumed the current Tamsui-Xiangshan route in 2014.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

For many centuries from the medieval to the early modern era, the island port of Hirado on the northwestern tip of Kyushu in Japan was the epicenter of piracy in East Asia. From bases in Hirado the notorious wokou (倭寇) terrorized Korea and China. They raided coastal towns, carrying off people into slavery and looting everything from grain to porcelain to bells in Buddhist temples. Kyushu itself operated a thriving trade with China in sulfur, a necessary ingredient of the gunpowder that powered militaries from Europe to Japan. Over time Hirado developed into a full service stop for pirates. Booty could

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them

Politically charged thriller One Battle After Another won six prizes, including best picture, at the British Academy Film Awards on Sunday, building momentum ahead of Hollywood’s Academy Awards next month. Blues-steeped vampire epic Sinners and gothic horror story Frankenstein won three awards each, while Shakespearean family tragedy Hamnet won two including best British film. One Battle After Another, Paul Thomas Anderson’s explosive film about a group of revolutionaries in chaotic conflict with the state, won awards for directing, adapted screenplay, cinematography and editing, as well as for Sean Penn’s supporting performance as an obsessed military officer. “This is very overwhelming and wonderful,” Anderson