The international community of China human rights watchers lost a legendary figure last month with the passing of Robin Munro, who was one of the key Western observers of the 1989 Tiananmen student protests in Beijing. He died on May 19 in Taipei at age 67.

Tributes have poured forth from ranking journalists and top figures at Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, China Labor Bulletin and London’s School of Oriental & African Studies (SOAS), calling Munro a “legend,” who set the “gold standard” for human rights documentation in the post-Tiananmen era.

“Munro was [Human Rights Watch’s] first researcher on China. He was the last known Westerner to leave Tiananmen Square. He did pathbreaking work on China’s horrible orphanages and on labor rights,” tweeted Kenneth Roth, executive director of Human Rights Watch.

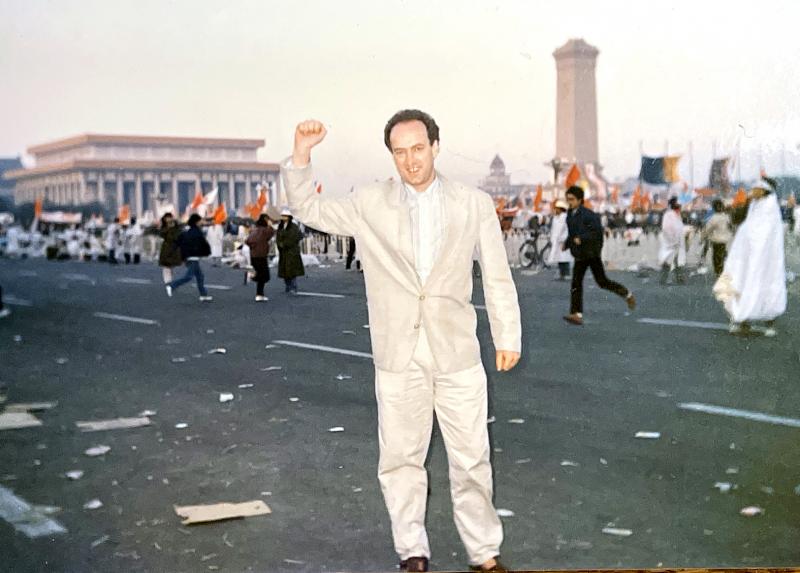

Photo: David Frazier

“Robin helped many Chinese dissidents, who might otherwise have died in prison, to gain their freedom. I was one of them,” wrote Tiananmen democracy activist Han Dongfang (韓東方).

“His work on China human rights issues was hugely important,” tweeted Bloomberg reporter Benjamin Robertson.

HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES IN CHINA

Photo: Bloomberg

Over the last three decades, Munro authored groundbreaking reports on China’s organ harvesting, abuses in orphanages, psychological torture of political prisoners and early rights abuses in Xinjiang.

Munro came into the human rights field when China was largely sealed off to the West and its human rights issues were little understood. He began his career in 1979 with Amnesty International in London, then in 1987 moved over to Human Rights Watch in New York. In early 1989, Human Rights Watch sent him to Hong Kong as its first dedicated China researcher and office director.

Within months of the posting to Hong Kong, student demonstrations erupted in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, and Munro traveled north to witness them first hand. He is acknowledged as the last Western observer to leave the square early on the morning of June 4, 1989, staying on to witness the arrival of the People’s Liberation Army. Munro’s documentation of that event, and interviews he gave on Western TV news programs, became crucial to the world’s understanding of what was happening on the ground.

Photo courtesy of Huang Pao-lien

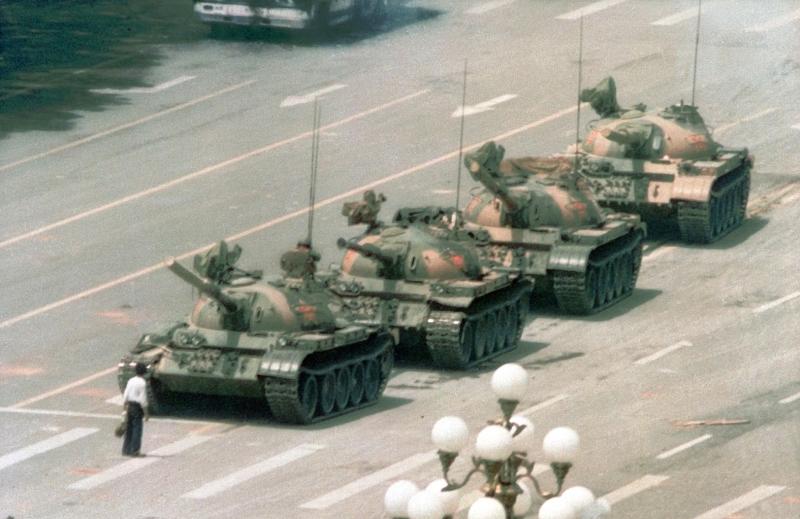

A recent obituary from SOAS observed that Munro’s “account made the important point that it was not in fact students who were massacred in the Square, but rather the citizens of Beijing — the laobaixing (老百姓) — who were supporting the students in the streets outside the Square and were slaughtered there.”

In 1990, on Tiananmen’s first anniversary, Munro explained in an article in the US magazine The Nation, “A massacre did take place — but not in Tiananmen Square, and not predominantly of students. The great majority of those who died… were workers, or laobaixing (“common folk” or “old hundred names”), and they died mainly on the approach roads in western Beijing.”

Later in the article he explained that the reason these common citizens were “mercilessly punished [was] in order to eradicate organized popular unrest for a generation.”

Photo: AP

“Journalism may be only the rough draft of history,” wrote Munro, “but if left uncorrected it can forever distort the future course of events.”

“I think that a key part of Robin’s success as an activist was his sense of responsibility, as a scholar, to the truth as supported by evidence. Despite his passion... he never exaggerated,” observed Donald Clarke, a specialist in Chinese law at George Washington University and one of Munro’s closest personal friends.

MAN OF THE PEOPLE

Robin Munro was born in London on June 1, 1952. At the age of six, he moved with his family to Scotland, where his father was a lecturer at the Veterinary School of Glasgow University.

His mother’s line included three generations of missionaries in China, going back to the 1800s. His own mother was born in 1918 in Swatow, China — present day Shantou, Guangdong Province — but as political upheaval swept China in the 1920s, the family returned to Edinburgh in 1925.

Munro began his studies at Edinburgh University in 1969, but dropped out for some time to live in a hippie commune on the Balearic island of Formentera, just next to Ibiza. In Scotland, he also drove a public bus, an item he kept on his CV for years as a nod to his labor credentials. When he returned to school in 1974, he changed his academic tack and began studying Chinese.

He traveled to China for the first time as a visiting student from 1977 to 1979, a period which perfectly straddled the end of the Cultural Revolution. In his first year at Peking University, his classmates and roommates were workers, peasants and soldiers assigned to the university by the Communist Party, while in his second year he studied with intellectuals returning from rural communes, who had been sent down by Chairman Mao Zedong (毛澤東).

In the decade following the Tiananmen massacre, Munro helped numerous fleeing Chinese dissidents attain asylum in the West.

He also “did pathbreaking research” — published as reports and books — “on China’s psychiatric abuse of political prisoners, abuses in orphanages and organ harvesting of convicts. He also broke new ground reporting on Inner Mongolia, the laogai (勞改, “reform through labor”) detention system in Xinjiang and repression of Catholics in Hebei province,” according to a statement by Human Rights Watch.

“All of these works constituted the first serious and scholarly examination of the problems they addressed,” wrote Clarke.

One of the Chinese dissidents Munro helped, Li Jinjin (李進進), tweeted, “It shocked me, the sad news that my friend Robin [is] gone. He met me after I was released from Qincheng Jail in Beijing in…1991. He helped me come to the United States in…1993.”

PLIGHT OF ACTIVISTS

Munro chronicled the plight of Li and other activists in the 1993 book Black Hands of Beijing, which he co-authored with George Black.

Another dissident assisted by Munro was one of the founders of the Beijing Workers’ Autonomous Federation, the aforementioned Han Dongfeng, whom Munro became friends with through frequent visits to the workers encampment in Tiananmen Square.

Following the 1989 crackdown, Han was imprisoned for two years and placed in a cell with tuberculosis sufferers. Han eventually lost a lung to the disease and might have died had Munro not lobbied for his release and helped arrange medical treatment.

In 1994, Han had settled in Hong Kong and there founded an NGO, China Labor Bulletin advocating for labor rights in China. Munro began working with him at the organization a decade later in 2003.

“Robin worked tirelessly over the past two decades to provide legal assistance for tens of thousands of Chinese workers seeking justice through the court system,” Han wrote in a recent tribute.

“Many of them had suffered terrible work injuries, contracted occupational diseases or were desperate to get the back pay owed for months, even years, of hard labor. Many workers faced imprisonment for defending their legal rights. These workers and their families should know that it was this Scotsman, Robin Munro, who helped them obtain justice.”

In 2004, Munro married the Taiwanese writer Huang Pao-lien (黃寶蓮), today a well-known author of 16 books of fiction and non-fiction.

PERSONAL CONNECTION

In 2011, the couple moved from Hong Kong to Taipei, after Munro was set upon by medical issues. For a decade, he managed to beat his illness, living happily in semi-retirement on the slopes of Yangmingshan, north of Taipei.

I met him there last year, where he helped me make a digital recording of old analogue audio tape, using one of his vintage reel-to-reel tape players.

Munro was a high-end audiophile, who spoke gleefully of his German hand-crafted turntable arm, his 1950s French amplifier and his unbelievable music collection, which included some of the first ever stereo recordings on analogue tape. I now regret that I never had the chance to return so that he could play them for me — he had of course made the generous offer, and spoke with vast and marvelous knowledge on the nuances of high fidelity.

Munro was taken by a sudden illness in April and died on May 19 at Taipei Veterans Memorial Hospital. He is survived by his sister Sandra and wife Huang Pao-lien, who was by his side to the last.

Munro influenced an entire generation of human rights workers in Asia, and recent numerous tributes acknowledge this legacy.

Their sentiments are best summed up in the eulogy of his longtime friend, Donald Clarke: “For many in the human rights community, his passing marks the loss of a giant figure. For his wife, sister and friends, it marks the loss of a part of themselves. For everyone, his life is a reminder of what matters in this world. In Shakespeare’s words, ‘His life was gentle, and the elements mixed so well in him that Nature might stand up and say to all the world, This was a man.’”

The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), and the country’s other political groups dare not offend religious groups, says Chen Lih-ming (陳立民), founder of the Taiwan Anti-Religion Alliance (台灣反宗教者聯盟). “It’s the same in other democracies, of course, but because political struggles in Taiwan are extraordinarily fierce, you’ll see candidates visiting several temples each day ahead of elections. That adds impetus to religion here,” says the retired college lecturer. In Japan’s most recent election, the Liberal Democratic Party lost many votes because of its ties to the Unification Church (“the Moonies”). Chen contrasts the progress made by anti-religion movements in

Taiwan doesn’t have a lot of railways, but its network has plenty of history. The government-owned entity that last year became the Taiwan Railway Corp (TRC) has been operating trains since 1891. During the 1895-1945 period of Japanese rule, the colonial government made huge investments in rail infrastructure. The northern port city of Keelung was connected to Kaohsiung in the south. New lines appeared in Pingtung, Yilan and the Hualien-Taitung region. Railway enthusiasts exploring Taiwan will find plenty to amuse themselves. Taipei will soon gain its second rail-themed museum. Elsewhere there’s a number of endearing branch lines and rolling-stock collections, some

Could Taiwan’s democracy be at risk? There is a lot of apocalyptic commentary right now suggesting that this is the case, but it is always a conspiracy by the other guys — our side is firmly on the side of protecting democracy and always has been, unlike them! The situation is nowhere near that bleak — yet. The concern is that the power struggle between the opposition Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and their now effectively pan-blue allies the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) intensifies to the point where democratic functions start to break down. Both

This was not supposed to be an election year. The local media is billing it as the “2025 great recall era” (2025大罷免時代) or the “2025 great recall wave” (2025大罷免潮), with many now just shortening it to “great recall.” As of this writing the number of campaigns that have submitted the requisite one percent of eligible voters signatures in legislative districts is 51 — 35 targeting Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) caucus lawmakers and 16 targeting Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) lawmakers. The pan-green side has more as they started earlier. Many recall campaigns are billing themselves as “Winter Bluebirds” after the “Bluebird Action”