In 1894 Hong Kong was the jumping off point for the great third wave of bubonic plague, which had originated in Yunnan back in the 1850s and was slowly working its way around Asia. Spreading in south China, it eventually reached Canton and Hong Kong, where it killed by the thousand that terrible year. In Hong Kong it remained endemic until 1929. In Yunnan the reservoir of plague still exists.

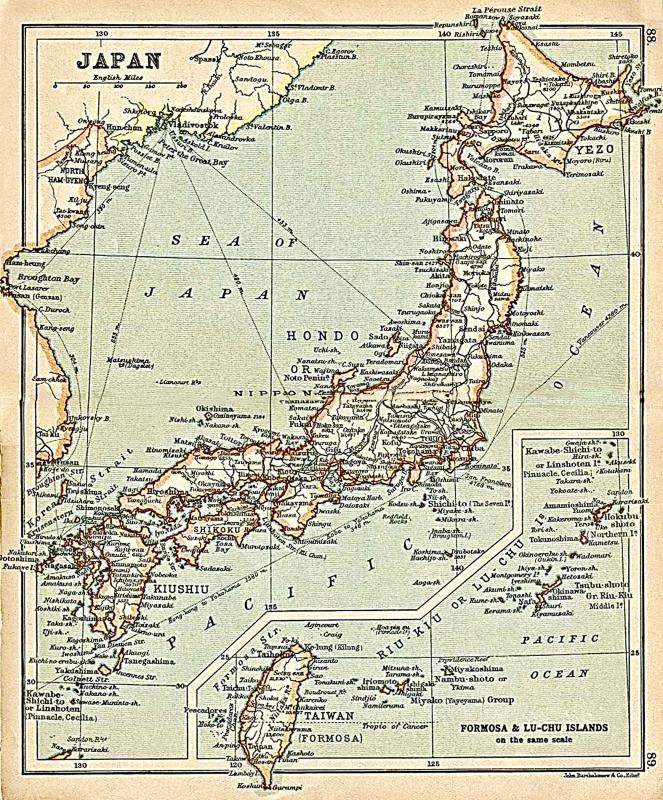

That globalized world was connected by steamships, which soon brought it to Taiwan, newly incorporated into the Japanese empire. Kodama Gentaro, formerly army vice-minister, had just been made governor-general of Taiwan, and he brought in politician and administrator Goto Shinpei to run the civilian side of the Japanese administration.

PUBLIC HEALTH

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Not by coincidence, Goto had a public health and medical background. He had studied in Germany, served as chief of the Army Quarantine office and helped in the construction of new water and sewage works in Tokyo. He immediately set to work organizing Taiwan’s health administration along what he saw as scientific principles.

Goto’s original plan called for two agencies to handle the public health interface with the population, a sanitary police force he based on the ideas of a now-obscure German thinker, Louis Pappenheim, and a public medical service. In 1901 the government created the sanitary police force under a law that promulgated a detailed series of public health responsibilities for the new unit. In 1904 Goto brought in Takagi Tomoe, a close associate, to run the sanitary police force.

Control of epidemic disease was a major thrust of early Japanese colonial policy. In the early 1900s Taiwan suffered roughly two thousand deaths annually from bubonic plague, figures which peaked at around 3,300 deaths in 1901 and 1904. Cholera and malaria were also threats as well.

Photo courtesy of the Taichung City Government

Takagi, as Academia Sinica scholar Liu Shiyung (劉士永) describes, made a key change to Goto’s ideas, integrating them with the famous baojia system (hoko in Japanese) that successive imperial governments had used to control their territories. This system had its origin back in the China’s Warring States period. Under the Qing Dynasty it reached its apex, with 10 families comprising a jia, and 10 jia constituting a bao. Each bao had an elected chief who maintained records, acted as the government’s johnny on the spot and maintained public order.

This innovation brought the colonial government right into the local communities. On the one hand, it helped the government fight Taiwan’s numerous medical problems, from disease to opium. Yet on the other, the police acted as an arm of the surveillance state.

As scholar Reo Matsuzaki has observed, Takagi’s innovation enabled the Japanese to make “community leaders more readily disciplined, by containing the influence they exerted within Taiwanese society to the level of villages and neighborhoods.” This would become a feature of later Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) rule as well.

The plague, known in Taiwan as the “Hong Kong disease,” quickly spread. Goto set up quarantine stations at the ports, making them permanent in 1899 at Keelung and Tamsui and issued an edict that required the public to report cases to the authorities. A strict quarantine program was erected.

LOCAL NEEDS, GOVERNMENT DEMANDS

Local community leaders, the face of the government at the local level, constantly navigated the tension between local needs and colonial government demands. When plague numbers rose, it was the community leaders in the hoko system who had to burn local buildings and isolate the sick. They had to do this even though in most cases they knew the people they were hurting, and knew that local families did not want to send members with the plague off to quarantine camps, where death was almost certain.

The Japanese also conducted a national rat-catching campaign, to help eradicate bubonic plague. The hoko oversaw the efforts of local communities, establishing local programs to encourage the public to catch rats, which were sent off to Japanese scientists for analysis.

In Taipei, for example, the locals had a monthly quota of rats, and were fined or rewarded accordingly. Between 1904 and 1908, up to 4.6 million rats were caught annually. Bubonic plague was eliminated in Taiwan by 1917, according to Matsuzaki.

Goto had conducted the world’s first mass immunization campaign against cholera in Japan before coming to Taiwan, and he sought to replicate his successes. He hired a Scottish engineer to lay out a new water system for Taipei, to make the city fit for Japanese to live in (the system disproportionately helped the colonial rulers). Many of these pipes remained in use well into the modern era. The new system reduced the incidence of summer diarrhea for Japanese to roughly one-fifth of that of Taiwanese.

The Japanese ran into problems right away with disease reporting and with vaccination programs: the public trusted traditional doctors more than Japanese doctors. Moreover, with the lack of Japanese medics, local doctors were responsible for reporting diseases and deaths. In response, they integrated the local traditional medicine doctors into the colonial health program. In 1902 the colonial government promulgated a certification program to allow traditional doctors to help in the vaccination program.

The Japanese were experienced in handling cholera and bubonic plague, but malaria was new to them. The anti-malaria program was thus delayed, finally getting rolling in 1919 after an extended internal debate. When it finally arrived, it met with much local resistance. Japanese “science” viewed Taiwan as dirty and pre-modern, and areas once cleansed of malaria were required to have a park-like air, exhibiting how colonial control, modernization and hygiene were overlapping concepts for Taiwan’s Japanese rulers.

For Taiwanese, malaria was part of daily life, like the common cold. According to environmental historian Ku Ya-wen (顧雅文), they saw the scientific claims of the Japanese as nonsense and anti-mosquito activities as a costly imposition on their lives. Japanese “science” clashed with local “knowledge.”

For example, when the new anti-malarial policy required that Taiwanese remove the stands of bamboo from around their homes, which Japanese administrators regarded as making houses look dark and dirty, and as blocking airflow, there was vocal opposition. Traditionally, during attacks of the plague, the locals would burn incense by the bamboo stands. Removal was regarded as unlucky. Stands of bamboo were also believed to block thieves.

What lessons are here? It’s tempting to equate the anti-vax noise on social media and by prominent individuals in society with the tradition-based resistance to a colonial power presenting colonial control as scientific modernity.

But that would be wrong.

Modern anti-science movements are similar in thrust to the claims of Japanese administrators that stands of bamboo around houses represent local ignorance. Just like the Japanese, anti-vaxxers selectively mine modernity for ideas that are merely another a form of power and control over the minds and bodies of others, masquerading as superior knowledge. Just like the Japanese, they’re in it for the money and benefits to themselves.

And just like the Japanese, they should be resisted. Get vaccinated.

Notes from Central Taiwan is a column written by long-term resident Michael Turton, who provides incisive commentary informed by three decades of living in and writing about his adoptive country. The views expressed here are his own.

March 10 to March 16 Although it failed to become popular, March of the Black Cats (烏貓進行曲) was the first Taiwanese record to have “pop song” printed on the label. Released in March 1929 under Eagle Records, a subsidiary of the Japanese-owned Columbia Records, the Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) lyrics followed the traditional seven characters per verse of Taiwanese opera, but the instrumentation was Western, performed by Eagle’s in-house orchestra. The singer was entertainer Chiu-chan (秋蟾). In fact, a cover of a Xiamen folk song by Chiu-chan released around the same time, Plum Widow Missing Her Husband (雪梅思君), enjoyed more

Last week Elbridge Colby, US President Donald Trump’s nominee for under secretary of defense for policy, a key advisory position, said in his Senate confirmation hearing that Taiwan defense spending should be 10 percent of GDP “at least something in that ballpark, really focused on their defense.” He added: “So we need to properly incentivize them.” Much commentary focused on the 10 percent figure, and rightly so. Colby is not wrong in one respect — Taiwan does need to spend more. But the steady escalation in the proportion of GDP from 3 percent to 5 percent to 10 percent that advocates

From insomniacs to party-goers, doting couples, tired paramedics and Johannesburg’s golden youth, The Pantry, a petrol station doubling as a gourmet deli, has become unmissable on the nightlife scene of South Africa’s biggest city. Open 24 hours a day, the establishment which opened three years ago is a haven for revelers looking for a midnight snack to sober up after the bars and nightclubs close at 2am or 5am. “Believe me, we see it all here,” sighs a cashier. Before the curtains open on Johannesburg’s infamous party scene, the evening gets off to a gentle start. On a Friday at around 6pm,

A series of dramatic news items dropped last month that shed light on Chinese Communist Party (CCP) attitudes towards three candidates for last year’s presidential election: Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲), Terry Gou (郭台銘), founder of Hon Hai Precision Industry Co (鴻海精密), also known as Foxconn Technology Group (富士康科技集團), and New Taipei City Mayor Hou You-yi (侯友宜) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). It also revealed deep blue support for Ko and Gou from inside the KMT, how they interacted with the CCP and alleged election interference involving NT$100 million (US$3.05 million) or more raised by the