June 28 to July 4

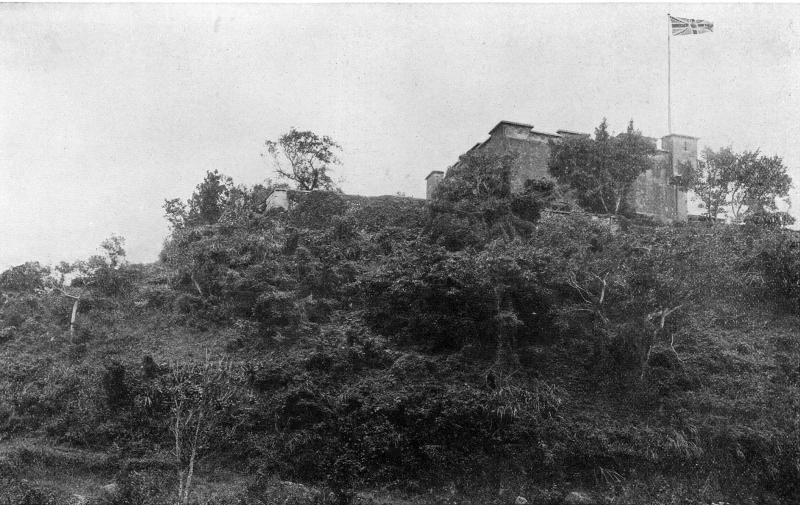

During the late 1970s, hot-blooded young protesters were known to break into the guarded Fort San Domingo in Tamsui to protest what many considered the “shame of the nation.”

What is now one of northern Taiwan’s top tourist attractions was strictly off limits to the public then, walled off and shrouded in mystery. In fact, the government didn’t even own the more than three-century-old complex, as the British had permanently leased it as their consulate until Chinese pressure forced them to remove all official representation in Taiwan in 1972. The fort then briefly served as the Austrian embassy, but that country broke ties with Taiwan for China within a few months.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The events caused an uproar among Taiwanese, and calls for the government to reclaim the fort began around then. But instead the British transferred it to the Americans, who continued to administer the structure after they, too, severed relations with Taiwan in 1979.

Writer and academic Lee Li-kuo (李利國) published several articles in 1977 about the fort’s ownership in Cactus Magazine (仙人掌雜誌). Author and popular hiking blogger Tony Huang (黃育智) writes that he learned about the fort for the first time through Lee’s work: “Few of us had any idea that there was still a foreign concession in Taiwan, and that our own citizens were not allowed to set foot in it. I was young, passionate and full of patriotism back then, and the truth made my blood boil.”

On June 30, 1980, the government finally took possession of the fort. The handover ceremony can be seen on a Chinese TV System (華視) clip on YouTube, which concludes with the Republic of China (ROC) flag being raised on the top of the fort. It was opened to the public four years later.

Photo courtesy of Academia Sinica

PERMANENT LEASE

The Spanish, who colonized parts of northern Taiwan during the 1620s, built the original wooden Fort San Domingo in 1629. They razed the fort in 1642 before they were expelled by the Dutch, who built a new structure in 1644. It was named Fort San Antonio.

For many years, people believed that the current structure was the original Fort San Domingo, and even today it still retains the name. Historian Tsao Yung-ho (曹永和) is often credited for confirming in 2005 that the structure is in fact Fort San Antonio.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

The Qing Dynasty took possession of the fort when it control of Taiwan in 1683, and renovated it in 1724. They were forced to open Tamsui to foreign traders per the 1858 Treaty of Tianjin, leading to the need for a British consulate. This consulate initially operated out of a rented private residence, but in 1867 the British signed an agreement to permanently lease what was then-called the Helanlou (荷蘭樓), or “Dutch Fort.”

“It is agreed that so long as Her Majesty’s government continues to pay the above stipulated lease for the said land they shall be allowed to rent the same and the Chinese government shall not be empowered to refuse to continue the lease,” the agreement read.

The British made many repairs and additions to the structure, painting it red and adding a two-story brick building in 1891 to serve as the consulate.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

After Qing ceded Taiwan to Japan in 1895, the British offered to sell the fort to the new colonizers and move their consulate to Dadaocheng (大稻埕). But the deal fell through as the Japanese were not willing to pay the asking price. In 1909, the British signed a new perpetual lease for the property with the Japanese.

The consulate closed in 1941 as the two sides fought during World War II, and the British returned to the fort under the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1946.

BROKEN TIES

At this point, the permanent lease appeared to still be in effect as the ROC had decided to honor the agreements that the Qing had signed with foreigners before its establishment in 1912.

To the dismay of the new government, the UK in January 1950 decided to recognize the People’s Republic of China and break ties with Taiwan. Yet it maintained the consulate in Tamsui, creating a curious situation where it had official representation in a country it didn’t recognize. The government didn’t seem to mind; it was beneficial to them to keep relations with the British.

This lasted until March 1972, shortly after China replaced Taiwan in the UN. In adherence to the “one-China” policy, the UK announced that it would remove its consulate from Taiwan. It wanted to completely cut official relations with Taiwan, with visas being handled through designated airlines and commerce conducted through businesses in Taipei.

Despite public furor, the government was reluctant to ask for the fort back. While they owned the land the fort stood on, the consulate building was built by the British, who wanted compensation for it. Also, they were wary of antagonizing the British since they had many interests in Hong Kong.

Nearby Aletheia University, which is affiliated with the Taiwan Presbytarian Church, was one of several parties hoping to use the building. They negotiated with the British from 1972 to 1978, and although nothing came from it, they’re credited for tackling the issue long before the government took action.

Negotiations dragged on until February 1980, when the government terminated the lease and gave a deadline of June 30 to the British to work out a deal. By then, relations between the two sides had stabilized with the establishment of the Anglo-Taiwan Trade Committee in 1976.

Working with National Taiwan University’s civil engineering and urban planning experts, they renovated the property and designated it a first-grade historic site. On Christmas Day, 1984, tens of thousands of people made their way to Tamsui to finally get a look at the enigmatic fort they had been hearing so much about.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

For many centuries from the medieval to the early modern era, the island port of Hirado on the northwestern tip of Kyushu in Japan was the epicenter of piracy in East Asia. From bases in Hirado the notorious wokou (倭寇) terrorized Korea and China. They raided coastal towns, carrying off people into slavery and looting everything from grain to porcelain to bells in Buddhist temples. Kyushu itself operated a thriving trade with China in sulfur, a necessary ingredient of the gunpowder that powered militaries from Europe to Japan. Over time Hirado developed into a full service stop for pirates. Booty could

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them

Politically charged thriller One Battle After Another won six prizes, including best picture, at the British Academy Film Awards on Sunday, building momentum ahead of Hollywood’s Academy Awards next month. Blues-steeped vampire epic Sinners and gothic horror story Frankenstein won three awards each, while Shakespearean family tragedy Hamnet won two including best British film. One Battle After Another, Paul Thomas Anderson’s explosive film about a group of revolutionaries in chaotic conflict with the state, won awards for directing, adapted screenplay, cinematography and editing, as well as for Sean Penn’s supporting performance as an obsessed military officer. “This is very overwhelming and wonderful,” Anderson