As we have come out of an era of silenced voices and confiscated photographs, we know the preciousness of those slivered shards of memory: the pieces of writing that were half-veiled critiques of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) authoritarian regime, trying to hide behind stock phrases that could not be construed as sedition, and yet bite; the faded and poorly-focused photographs were usually taken by amateurs, who yet were driven to capture the fleeting moment when a few foolhardy souls ventured to gather and join in protest.

The negatives and pictures, fading and molding in Taiwan’s humid climate as they lay for years in hidden and forgotten places, fared worse than the written record. For example, Chen Po-wen (陳博文), the main photographer during the 1979 Kaohsiung Incident (美麗島事件), ran an X-ray processing shop in Taichung where he could process his own photographs; as police moved in to arrest him early in the morning in December 1979, Chen hid photo negatives between stacks of large X-rays, not re-discovered until the late 1990’s.

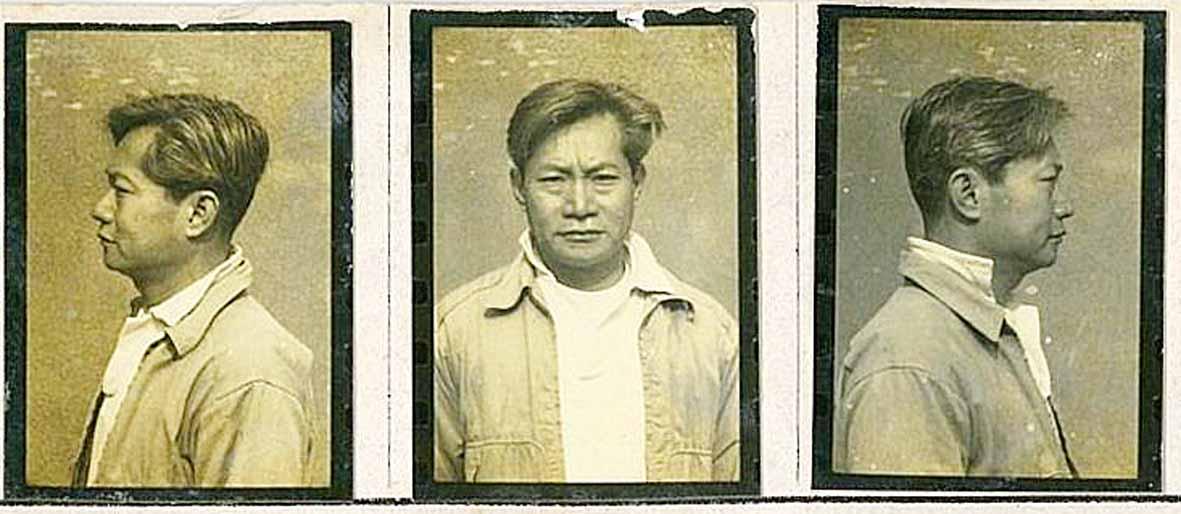

These photographs have since been the basis for several exhibitions. Other photos have been released by the National Archives Administration to relatives of political prisoners, but are not generally available. These early photos are even more precious because of their scarcity, and they tell us more about human nature than words, as we witness, for example, the faint look of bravado on the face of a person facing the firing squad.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Foundation for Democracy

COPYRIGHT RESTRICTIONS

And now as we try to recover and transmit history, we face a new hurdle: copyright restrictions. Aside from the restrictions that claim to protect ownership for private parties, we face exaggerated privacy claims, such that names on documents from the national archives are often blacked out. So those who are motivated to research and write history face an obstacle course of legal, financial and administrative hurdles.

Now let me get specific. The Taiwan Foundation for Democracy (TFD) was founded in 2003 at the request of then-president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁); funding came from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The titular head was the KMT’s Wang Jin-pyng (王金平), the then-speaker of the Legislative Yuan. Kao Ying-mao (高英茂), a professor of political science, was named the director. TFD has been able to promote international recognition for Taiwan’s advance towards democracy, a considerable part of its new legitimation in international society.

Photo courtesy of Vinay Chen

The first activity of the TFD — “The Struggle for Democracy and Human Rights: A Journey of Remembrance and Appreciation”(感恩與巡禮: 國際友人對台灣民主與人權奮鬥的回顧) — was to invite back to Taiwan on Dec. 8 and Dec. 9, 2003, 30 foreign nationals who had been expelled in the period of martial law. The list of invitees was drawn up by Lynn Miles, who knew most of them from his years running an underground human rights network based in Osaka.

This program included some KMT-affiliated figures who were willing to come, such as KMT legislator John Chiang (蔣孝嚴), a son of former president Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國). It was an emotional moment when the elder sister of Chen Wen-cheng (陳文成), a mathematics professor from Pittsburgh found dead on July 3, 1981, the day after being taken in for questioning by the security agencies, addressed Chiang as a fellow family member of White Terror victims.

A further highlight was that US missionary Milo Thornberry and his wife Judith Thomas revealed that they had carried out the January 1970 escape of democracy pioneer Peng Ming-min (彭明敏) from house arrest in Taiwan — not the US Central Intelligence Agency, as many had assumed. My significant part was to insist that we make an enduring record of each person’s experience, on videotape.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Foundation for Democracy

Subsequently Lynn Miles and I used these for our 500-page, 2008 book, A Borrowed Voice: Taiwan Human Rights through International Networks, 1960-1980 (我的聲音借你: 台灣人權訴求與國際聯絡網). This book remains the main record of this history, and will be available for free download in English and Chinese next month through the Jing-Mei White Terror Memorial Park (白色恐怖景美紀念園區), under the title International Contributors to Taiwan Human Rights: vr360.nhrm.gov.tw/ftpp/.

HUMAN RIGHTS EXHIBITION

The Jing-mei White Terror Memorial Park last year began to plan an exhibition for December on the overseas contributors to Taiwan human rights, and asked me to be a consultant. Soon, however, the expanding pandemic nixed our plans for inviting the few surviving foreign participants. So I planned a colorful book to accompany the exhibit, and researched their later lives for an updated account. Then the contractor for the exhibit contacted the TFD, and was told none of the 2003 materials could be found; perhaps they were dumped during the Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) presidency (2008-2016), when it was rumored that TFD itself barely survived.

The pictures were all on my computer, but it took considerable searching before I found the 2003 video interviews on CD’s stacked inside plastic crates on my porch — many soaked in a recent typhoon, but fortunately spared. The contractor made copies and gave them to TFD, and requested formal permission to use them.

And then I waited. That was over six months ago. After many internal pass-the-bucks the contractor was told that TFD legal consultants said that it could not provide permission because they do not hold permissions from those in the 2003 activity. But giving this specious excuse, thinking narrowly in terms of commercial copyright, TFD seems, more importantly, to be violating its mission to promote Taiwan’s image of liberty and democracy.

I just heard about this problem with TFD two weeks ago as I am almost finished, after about eight months’ work, putting together a 300-page book with biographies of nearly 90 participants, with most photos taken at the 2003 conference, then still relatively young and active. After consulting with several authors and reporters, I understand that use of pictures taken in public spaces do not require the permission of the persons whose picture is taken. Commercially, they belong to the photographer who has taken the picture, or to the institution that arranged for it.

However, I have learned from another historian that it is indeed very difficult to get any organization to sign off on permission to use photographs, if just perhaps because of bureaucratic inertia. Where the pictures can be paid for commercially, the process still takes considerable administrative time and effort. But government organizations in particular want to cover themselves from any potential indemnity and thus take a narrow interpretation for how written permissions should be provided for their publications with pictures.

Now I want to ask: who has the right to write history? And who is willing to spend the effort and is able to write history, if the doors to sources are closed?

I contend that we cannot treat historical materials like commercial property, in particular those dating from or dealing with Taiwan’s Martial Law era. It is not justified to say that these materials belong even to the leaders of the political movements of that time. Instead, they represent the mass phenomena of mobilization of thousands of people. And they are only meaningful if they are a legacy to the next generation. All institutions and holders should make these photographs open to public use. I intend to put all the photographs I hold onto a Web site with a statement that they can be used as public domain. We must create a rich historical record for future generations to freely read and see, if only they are willing.

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not

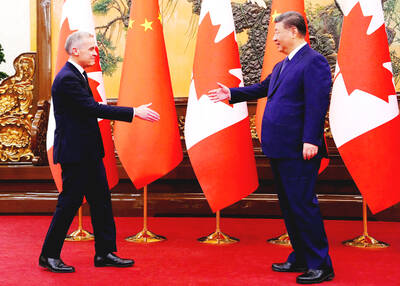

Britain’s Keir Starmer is the latest Western leader to thaw trade ties with China in a shift analysts say is driven by US tariff pressure and unease over US President Donald Trump’s volatile policy playbook. The prime minister’s Beijing visit this week to promote “pragmatic” co-operation comes on the heels of advances from the leaders of Canada, Ireland, France and Finland. Most were making the trip for the first time in years to refresh their partnership with the world’s second-largest economy. “There is a veritable race among European heads of government to meet with (Chinese leader) Xi Jinping (習近平),” said Hosuk Lee-Makiyama, director