Harboring an unrequited love for someone is one thing; following them, secretly taking pictures of them and visiting them at work every day is stalking. Chasing down and confronting their new boyfriend (even though he is a horrible person) in the name of justice, is stalking. There’s not really an excuse, no matter how well-intentioned one is.

Such behavior features heavily in My Missing Valentine (消失的情人節), which is available on Netflix after bagging five trophies during last year’s Golden Horse awards, including best feature and best director. It’s a skillfully edited and philosophical tale with a sweet and endearing protagonist portrayed by Patty Lee (李霈瑜). But what happens to her just doesn’t feel right.

An interesting device is that characters in the film each experience time differently. Lee’s character, Hsiao-chi, has been a step faster than others since birth. For example, she starts running in a race before the whistle is blown, and laughs during a movie before the punchline. The film begins with Hsiao-chi reporting to the police that she had lost a day — Valentine’s Day — with no memories of what happened.

Photo courtesy of Activator Marketing Company

Hsiao-chi is a shy yet personable 30-year-old post office worker who has never celebrated Valentine’s Day. She is cheerful and imaginative, and her quirky mannerisms and expressions grow on the audience and eventually carry the film.

Opposite Hsiao-chi is A-tai (Liu Kuan-ting, 劉冠廷), who is also shy and is always a step slower. Liu’s childlike and whimsical personality may serve to soften his otherwise creepy behavior. Of course, he’s a good person who doesn’t actually do Hsiao-chi any harm, but what’s shown is uncomfortable enough.

Without revealing the plot, the story becomes increasingly disturbing after the second half, and this reviewer cringed throughout the unsettling “romantic moments.” Yes, the film is meant to be surreal and not to be taken at face value, and this sort of story would be dark comedy gold if the screenwriters amped up the absurdity to the point that nobody could take it seriously (think Weekend at Bernie’s). But it doesn’t really work in a love story that’s supposed to be cute and heartwarming.

The idea that it’s not okay to stalk people is especially relevant in Taiwan today, given the reactions in April to the anti-stalking law that took years for the government to approve. The misogynistic comments displayed a grave misunderstanding of appropriate ways for men to interact with women, but Taiwanese movies and dramas still continue to perpetuate the unrequited stalker stereotype as a viable way to win someone’s heart.

During the bill’s latest discussion, lawyer and commentator Lu Chiu-yuan (呂秋遠) panned My Missing Valentine as a “horror film” and that the proper action for Hsiao-chi to do in real life is to call the police. Lu is quite right, and those who say “it’s just a movie” should look at the statistics and speak to those who have been stalked in the past.

Hsiao-chi is fortunate that A-tai is just a bit strange and silly, but the real world is not that kind. Perhaps the director wants to highlight how some people just can’t reach out or connect to others and resort to odd behavior, but it’s still not justifiable.

With the idea of respect and consent thrown out the window by the end of the film, it’s just hard to enjoy the good parts, which include some genuinely captivating moments, clever editing and wonderful dream sequences.

Lee, who is better known as a TV show host, should have won some sort of award for her acting, though, and hopefully we’ll see her in more productions in the future.

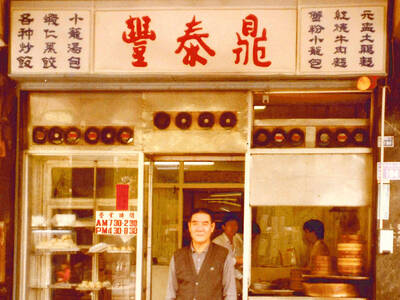

March 24 to March 30 When Yang Bing-yi (楊秉彝) needed a name for his new cooking oil shop in 1958, he first thought of honoring his previous employer, Heng Tai Fung (恆泰豐). The owner, Wang Yi-fu (王伊夫), had taken care of him over the previous 10 years, shortly after the native of Shanxi Province arrived in Taiwan in 1948 as a penniless 21 year old. His oil supplier was called Din Mei (鼎美), so he simply combined the names. Over the next decade, Yang and his wife Lai Pen-mei (賴盆妹) built up a booming business delivering oil to shops and

Indigenous Truku doctor Yuci (Bokeh Kosang), who resents his father for forcing him to learn their traditional way of life, clashes head to head in this film with his younger brother Siring (Umin Boya), who just wants to live off the land like his ancestors did. Hunter Brothers (獵人兄弟) opens with Yuci as the man of the hour as the village celebrates him getting into medical school, but then his father (Nolay Piho) wakes the brothers up in the middle of the night to go hunting. Siring is eager, but Yuci isn’t. Their mother (Ibix Buyang) begs her husband to let

The Taipei Times last week reported that the Control Yuan said it had been “left with no choice” but to ask the Constitutional Court to rule on the constitutionality of the central government budget, which left it without a budget. Lost in the outrage over the cuts to defense and to the Constitutional Court were the cuts to the Control Yuan, whose operating budget was slashed by 96 percent. It is unable even to pay its utility bills, and in the press conference it convened on the issue, said that its department directors were paying out of pocket for gasoline

On March 13 President William Lai (賴清德) gave a national security speech noting the 20th year since the passing of China’s Anti-Secession Law (反分裂國家法) in March 2005 that laid the legal groundwork for an invasion of Taiwan. That law, and other subsequent ones, are merely political theater created by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to have something to point to so they can claim “we have to do it, it is the law.” The president’s speech was somber and said: “By its actions, China already satisfies the definition of a ‘foreign hostile force’ as provided in the Anti-Infiltration Act, which unlike