AFP, PARIS

Carbon-polluting corporations and their investors face a rising tide of climate litigation, according to a report released Friday, two days after a Dutch court ordered oil giant Shell to slash its greenhouse gas emissions.

Companies operating in rich economies — Britain, the EU, Australia and especially the US, which accounts for the vast majority of cases to date — are most vulnerable to future legal action, business risk analysts Verisk Maplecroft found.

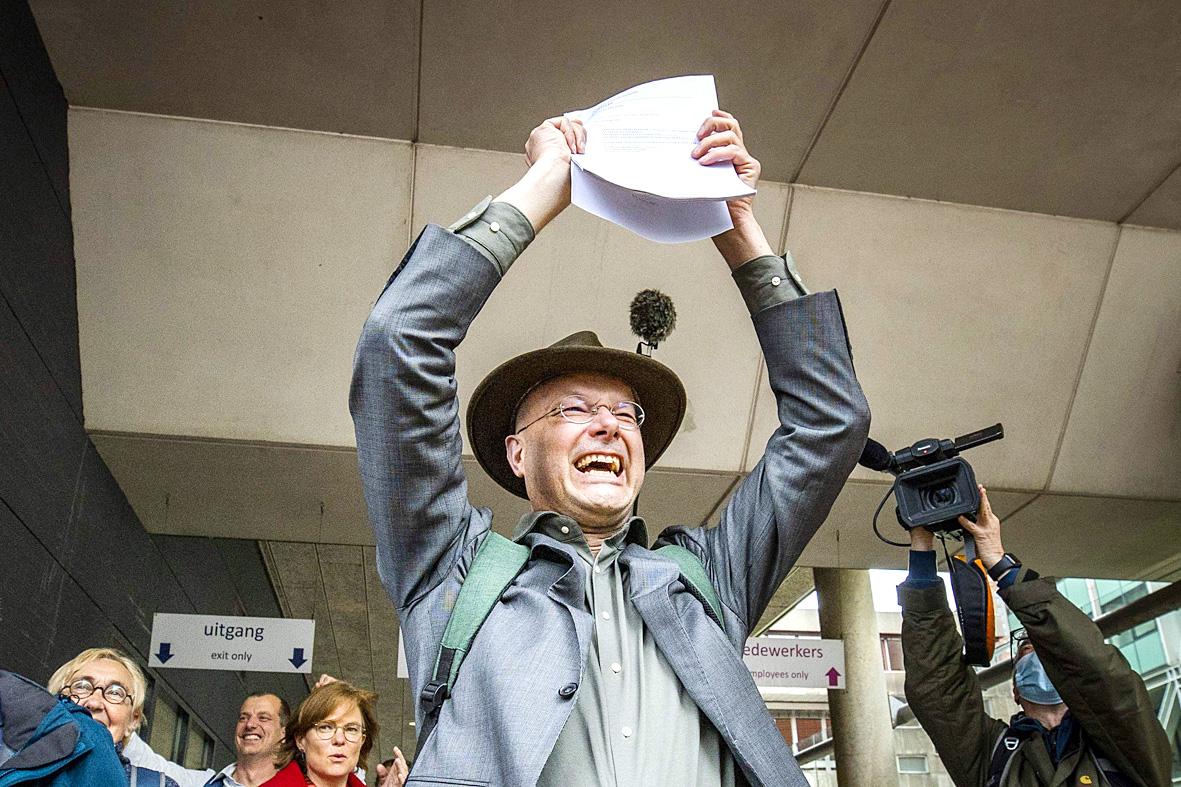

Photo: AFP

But the report also highlights a growing number of cases in developing countries despite more limited civil rights and a weaker rule of law.

“Our data points to a shift in major emerging economies, which might not bode well for the carbon-intensive companies operating there,” said Liz Hypes, Verisk Maplecroft’s senior environment and climate change analyst. “We are seeing climate litigation expand into countries where climate activism is lower but the threat of climate change is more significant.”

So far, most cases suing for strong climate action have been filed against governments.

But the Shell ruling, which ordered the Anglo-Dutch company to cut carbon emissions 45 percent by 2030, and other recent challenges to fossil fuel companies suggest the corporate world could see a crescendo of lawsuits.

Last month, New York City sued ExxonMobil and two other oil giants for greenwashing their products and intentionally misleading consumers about the extent to which they contribute to climate change.

An earlier bid by the Big Apple to hold five major gas and oil companies liable for damages caused by global warming was rejected weeks before by a federal court, but still inflicted reputational harm, Hypes said.

Also this week, investors brushed aside resistance from the company to install two activists board members at ExxonMobil, and at another annual investor meeting directed Chevron to deepen its emissions cuts.

More than 1,800 climate change-related cases have been filed in courts around the world in the last 25 years, most of them since 2010, according to a database maintained by the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School.

A “climate litigation index” in the new report assesses the likelihood of climate lawsuits in nearly 200 countries, based on prior litigation, public awareness, climate activism, and the strength of judicial systems. Not surprisingly, the US tops the risk ranking, followed by the UK, Australia, France and Germany. The next 17 countries on the list are all European, with the exception of Canada (10th) and Japan (18th).

But Mexico, Colombia, South Africa, Brazil and the Philippines are all in the top 50, with Indonesia, Pakistan and India just behind, the index showed.

As governments reacts to public pressure for faster climate action, corporations may run afoul of rapidly shifting regulatory environment.

Failure to curb emissions, and lack of transparency about business exposure to climate risk, can also damage brand reputation, even when courts rule in a company’s favour, as has happened in several US cases involving oil and gas majors.

Risk can also comes in the form of financial penalties as the scope of nature and climate litigation expands.

Companies, and their financial backers, “are facing genuine legal risks from which the repercussions may be significant,” Hypes said.

With fossil fuels generating 80 percent greenhouse gas emissions, oil and gas companies, and coal-powered electric utilities, are especially vulnerable to climate liability lawsuits.

That US assistance was a model for Taiwan’s spectacular development success was early recognized by policymakers and analysts. In a report to the US Congress for the fiscal year 1962, former President John F. Kennedy noted Taiwan’s “rapid economic growth,” was “producing a substantial net gain in living.” Kennedy had a stake in Taiwan’s achievements and the US’ official development assistance (ODA) in general: In September 1961, his entreaty to make the 1960s a “decade of development,” and an accompanying proposal for dedicated legislation to this end, had been formalized by congressional passage of the Foreign Assistance Act. Two

Despite the intense sunshine, we were hardly breaking a sweat as we cruised along the flat, dedicated bike lane, well protected from the heat by a canopy of trees. The electric assist on the bikes likely made a difference, too. Far removed from the bustle and noise of the Taichung traffic, we admired the serene rural scenery, making our way over rivers, alongside rice paddies and through pear orchards. Our route for the day covered two bike paths that connect in Fengyuan District (豐原) and are best done together. The Hou-Feng Bike Path (后豐鐵馬道) runs southward from Houli District (后里) while the

March 31 to April 6 On May 13, 1950, National Taiwan University Hospital otolaryngologist Su You-peng (蘇友鵬) was summoned to the director’s office. He thought someone had complained about him practicing the violin at night, but when he entered the room, he knew something was terribly wrong. He saw several burly men who appeared to be government secret agents, and three other resident doctors: internist Hsu Chiang (許強), dermatologist Hu Pao-chen (胡寶珍) and ophthalmologist Hu Hsin-lin (胡鑫麟). They were handcuffed, herded onto two jeeps and taken to the Secrecy Bureau (保密局) for questioning. Su was still in his doctor’s robes at

Mirror mirror on the wall, what’s the fairest Disney live-action remake of them all? Wait, mirror. Hold on a second. Maybe choosing from the likes of Alice in Wonderland (2010), Mulan (2020) and The Lion King (2019) isn’t such a good idea. Mirror, on second thought, what’s on Netflix? Even the most devoted fans would have to acknowledge that these have not been the most illustrious illustrations of Disney magic. At their best (Pete’s Dragon? Cinderella?) they breathe life into old classics that could use a little updating. At their worst, well, blue Will Smith. Given the rapacious rate of remakes in modern