I didn’t want to carry the regret with me for the rest of my life, so I dug out a few coins and stepped inside the little shop.

Traveling in Indochina years ago, I came across a bottle of “Premium Champagne” in a government-run store. Taking it off the shelf, I saw words that made me chuckle: “Manufactured by the Vietnam Fertilizer Corporation.”

When I got back to Taiwan, I kicked myself for not buying that champagne. Even if I never drank the contents, the bottle and its label would’ve made a great souvenir.

Photo: Steven Crook

This time around, I was standing in Chukuangkeng (出礦坑) in Miaoli County’s Gongguan Township (公館), facing a sign that read: Zhongyou Bingbang (中油冰棒, “CPC popsicles”).

CPC Corporation, Taiwan (台灣中油) is the country’s state-run petroleum and natural gas company. It’s as unlikely to manufacture frozen treats as a fertilizer company is to make booze.

It was also a sweltering afternoon. I needed something to cool me down, so I shelled out for a pineapple-flavored popsicle, and braced myself in case it tasted of gasoline.

Photo: Steven Crook

It turned out to be delicious but ordinary. Refreshed, I marched up the hill for a second time. There was far more to see at Chukuangkeng than I’d expected.

Taiwan has never been an oil-producer of significance, but it does have a long history of oil-and-gas exploration and exploitation. In fact, this corner of the northwest is one of the oldest still-productive oil-drilling sites in the world.

I’d arrived in Chukuangkeng thinking there’d be a museum of sorts and maybe some rusting infrastructure. I had no idea I’d end up spending the entire afternoon tramping around, examining relics and photographing machinery.

Photo: Steven Crook

Chukuangkeng is every bit as engrossing as better-known industrial-heritage destinations like Lintianshan (林田山) in Hualien. If you enjoyed Houtong Coal Mine Ecological Park (猴硐煤礦博物園區) and/or the Gold Ecological Park (黃金博物園區) in Jinguashi (金瓜石), do plan an excursion to Chukuangkeng.

The area’s past is celebrated in the Taiwan Petroleum Exhibition Hall (台灣油礦陳列館, also known as the Taiwan Oil Field Exhibition Hall). It’s by far the biggest building in a little village on the southbank of the Houlong River (後龍溪).

The exhibition hall features two floors of photographs, documents and maps. The first floor covers local history.

Photo: Steven Crook

The second floor, which focuses on the natural processes that create oil and the technologies used to extract it from the Earth, has some excellent models of rigs and derricks. I learned that, until the early 1950s, the drills used around Chukuangkeng were powered by steam engines that burned coal or wood. Later, they were driven by diesel engines.

STRIKING OIL

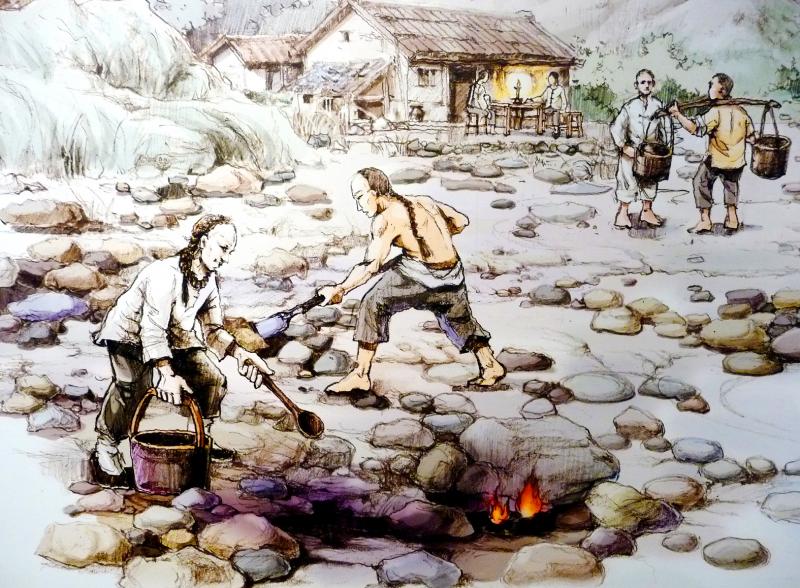

In 1817, a Hakka immigrant surnamed Wu (吳) noticed crude oil seeping into the river hereabouts. However, serious commercial exploitation didn’t begin until 1861, when a Hakka fugitive surnamed Qiu (邱) negotiated a deal with John Dodd, the Tamsui-based Englishman best known for his role in Taiwan’s tea industry.

Photo: Steven Crook

In the late 1870s, as the Qing Empire became more serious about governing and developing Taiwan, the provincial authorities hired two American technicians to drill for oil in the area. The results were disappointing and the Americans — whose complaints about lousy conditions and their opinions not being respected were uncannily similar to those of more recent expatriates — left after a year.

The numbers given in the museum aren’t clear, but there’s no doubt that, during the 1895-1945 period of Japanese colonial rule, oil production at Chukuangkeng hugely expanded. After World War II, CPC didn’t find any new oil fields worth developing, but they did come across valuable gas reserves.

As production declined, the number of CPC employees stationed here dwindled. Consequently, many of the facilities built to serve a once-bustling community have fallen into disrepair. Hardly a trace remains of the kindergarten, which once had 79 students. A wooden dormitory is a wreck. But the former clinic has been nicely restored.

Steel and iron are, of course, far more durable than wood. Along the 935m-long trail from the base of the inclined elevator (a funicular-like device that carried personnel and equipment up and down the hill) to the Memorial Stone Plaza (紀念碑廣場), I came across outcroppings of pipes, pressure gauges and gate valves, barnacled with peeling paint and rust.

The plaza is where the 550m-long inclined elevator (dormant since the late 1990s) terminated. The memorial there marks the site of No 33 Oil Well (三十三號油井), 385m above sea level — but it isn’t half as interesting as the winding equipment that remains inside the elevator’s machine room, or the disused derrick towering above the plaza.

Rather than return the same way, I opted to follow a narrow road CPC built to provide better access to No 33 Oil Well and other drilling sites.

I hadn’t gone more than 100m when I spotted a Taiwan Hare loitering ahead of me. These animals aren’t especially rare, but they do keep a low profile. In almost three decades of exploring rural Taiwan, I can count on one hand the number of times I’ve seen one.

Walking back to the Taiwan Petroleum Exhibition Hall took me about 45 minutes, during which I passed three active CPC sites, and saw signs pointing to several others.

Before crossing the river so I could catch a bus and begin the journey home, I spent a few minutes at Chukuangkeng No 1 Ancient Old Well (出礦坑第一號古油井).

A Japanese company began drilling here in September 1903. By the following January oil was flowing, albeit in small quantities.

The “rocking donkey” rig now at this location doesn’t look a century old, and it’s not as impressive as the other machinery that can be seen around Chukuangkeng. But it’s an authentic component of the area’s history — and, even if you’re no fan of fossil fuels, this is a corner of Taiwan you may well find fascinating.

Steven Crook has been writing about travel, culture and business in Taiwan since 1996. He is the author of Taiwan: The Bradt Travel Guide and co-author of A Culinary History of Taipei: Beyond Pork and Ponlai.

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

More than 75 years after the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four, the Orwellian phrase “Big Brother is watching you” has become so familiar to most of the Taiwanese public that even those who haven’t read the novel recognize it. That phrase has now been given a new look by amateur translator Tsiu Ing-sing (周盈成), who recently completed the first full Taiwanese translation of George Orwell’s dystopian classic. Tsiu — who completed the nearly 160,000-word project in his spare time over four years — said his goal was to “prove it possible” that foreign literature could be rendered in Taiwanese. The translation is part of

The other day, a friend decided to playfully name our individual roles within the group: planner, emotional support, and so on. I was the fault-finder — or, as she put it, “the grumpy teenager” — who points out problems, but doesn’t suggest alternatives. She was only kidding around, but she struck at an insecurity I have: that I’m unacceptably, intolerably negative. My first instinct is to stress-test ideas for potential flaws. This critical tendency serves me well professionally, and feels true to who I am. If I don’t enjoy a film, for example, I don’t swallow my opinion. But I sometimes worry

US President Donald Trump’s bid to take back control of the Panama Canal has put his counterpart Jose Raul Mulino in a difficult position and revived fears in the Central American country that US military bases will return. After Trump vowed to reclaim the interoceanic waterway from Chinese influence, US Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth signed an agreement with the Mulino administration last week for the US to deploy troops in areas adjacent to the canal. For more than two decades, after handing over control of the strategically vital waterway to Panama in 1999 and dismantling the bases that protected it, Washington has