A friend of mine, Katy Hui-wen Hung (洪惠文), who comes from an old, prominent family and has an abiding and deeply knowledgeable interest in Taiwan history, observed that one of the words for tomato in Hoklo (more commonly known as Taiwanese) is kamadi which appears to be taken from Tagalog, kamatis. She speculated that it moved up along the trade routes from Manila, an old trading town.

Small things like imported words signal an old, deep relationship between what is now the Philippines and this place we call Taiwan. Beginning in 1968, archaeological work at Baxian cave in Taitung County’s Changbin Township (長濱) has brought to light a culture labeled Changbin Culture (長濱文化),including a grave site and 40,000 tools and tool fragments made of stone, shell and bone. Often said to be 30,000 or even 50,000 years old, recent redating has made early dates of great antiquity less plausible, and the site appears to be around 10,000 years old.

“It is possible that Changbinhians came to Taiwan from the Southeast China, but also probably from the Phillipines,” observes a 2018 paper.

Photo courtesy of MOFA

AUSTRONESIAN CULTURE

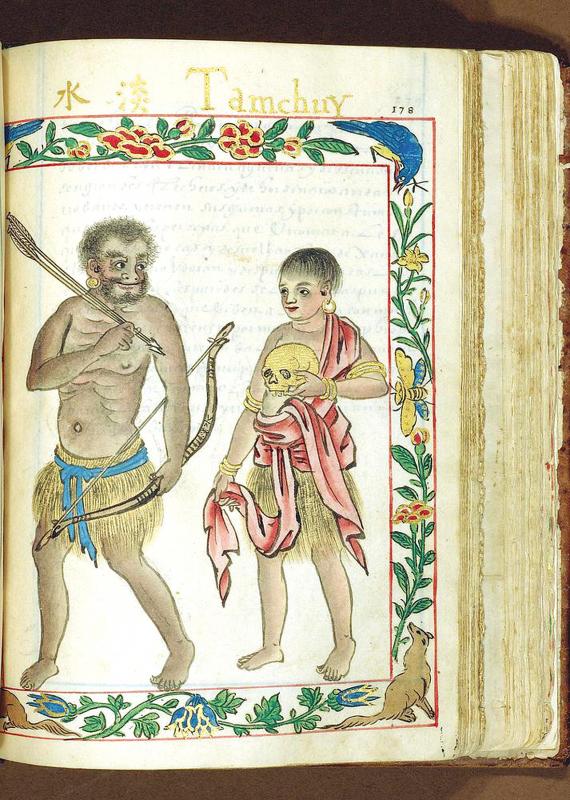

That was prior to the Austronesian settlement of Taiwan. If the Changbin people came up from the Philippines, they were likely Negrito peoples (a category that itself lumps together differing groups). Most readers will be familiar with the Pasta’ay, a famous Saisiyat festival that honors the small, black people who the Saisiyat people say they killed off, but in fact, legends of such people are known among other Aboriginal groups in Taiwan. Some tantalizing genetic evidence suggests DNA signals of these ancient peoples in modern Aboriginal populations in Taiwan, but it is not conclusive.

The Austronesians eventually moved out of Taiwan down to the Philippines, and were mixed with the Negrito populations already present. Some of them back-migrated to Taiwan, further complicating our understanding of the genetic relationships and the flow of peoples.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

In ancient times Taiwan Aborigines shipped unprocessed nephrite jade down to the Philippines (and to what is now Vietnam), where the locals shaped it into lingling-o ornaments, which were exported along the trade routes from Borneo to Vietnam, Cambodia and Peninsular Thailand, routes one scholar has called “one of the most extensive sea-based trade networks of a single geological material in the prehistoric world.”

Export of nephrite from Taiwan to Philippines continued from the settlement of Luzon by Austronesians around 4,000 years ago until the Iron Age began roughly 500 years into the Common Era, around 2,500 years. That stretch of time is hard to grasp — imagine if ancient Greek philosopher Socrates had manufactured a kind of ornament that was still being robustly made and traded today. That’s how long these networks operated.

After the 10th century, what is present-day Quanzhou on China’s coast rose as a major port, establishing trade routes that ran through the Penghu islands and along the south side of Taiwan to the Philippines. In the 12th century raiders showed up on the China coast. They are known in Chinese sources as Pisheye (毗舍耶), generally seen as “Visaya,” now a people of southern and central Philippines, but where they sailed from remains debated — the Chinese they raided perceived them as coming from across the Strait. It is easy to imagine them resting in the shallow bays of western Taiwan en route to China, just as later Chinese, Japanese and Dutch traders and pirates did as they moved through those waters. Though they are out of written history, people on Taiwan were still involved in exchanges with their counterparts in the Philippines.

In the sixteenth century Manila was taken by the Spanish, who sailed their galleons up the east side of Taiwan on their way to points north, and set up a little colony in northern Taiwan, which was eventually extinguished by the Dutch. When Ming Dynasty loyalist Koxinga (Cheng Cheng-kung (鄭成功) kicked the Dutch out of Taiwan, his next thought was to occupy the rich trading post of Manila. The connections were obvious to him.

It is interesting to speculate on what might have happened, had the Spanish empire expanded across Taiwan and fought off Koxinga. We are used to thinking of the Philippines and Taiwan as separate entities, but our current separation is an artifact of modern colonialism, Han settlement and historical contingency, a little gap in a long history of links. It could well have gone the other way, and our island would be full of Catholicized Han with Spanish surnames, perhaps struggling for independence from Manila.

Just a few score kilometers separate Taiwan from the Philippines, yet today the distance between them seems somehow vast. The Taiwan Public Opinion Foundation polled Taiwanese in 2019 and found that the Philippines was the second most disliked country, behind North Korea but ahead of China. Despite this, in 2019 the Philippines was the third most popular destination for Taiwanese tourists, behind Thailand and Vietnam.

NEW SOUTHBOUND POLICY

It seems intuitively obvious that Taiwanese investments in our nearest neighbor and longtime trading partner would have risen under the President Tsai Ing-wen’s (蔡英文) New Southbound Policy, yet Taiwanese investment in the Philippines peaked at around US$644 million in 2015 and is less than a fifth of that at present. Today roughly 150,000 workers from the Philippines are caring for our grandparents and working in our factories.

Just this year an agricultural internship program was established as part of Taiwan’s agricultural exchange program with the Philippines. Fifty farmers will learn Mandarin and then come to Taiwan to study Taiwanese agricultural techniques.

So much more could be done.

The Philippines should be the jewel in the crown of the New Southbound Policy. Not only do the islands have links to Taiwan going back millennia, today Manila, like Taipei, is a target of Chinese expansionism. The Bashi Channel between Luzon and the Hengchun Peninsula is periodically the site of displays of Chinese military power, of interest to Beijing because the infamous Nine-Dash Line cuts across it, yet also because it hosts key undersea cables that connect Asian countries.

Taiwan should be pursuing policies to draw the Philippines closer to Taiwan and counteract Chinese influence there. The government should consider expanding money for Mandarin instruction in the Philippines (the first Ministry of Education Mandarin program was only initiated in 2019), and funding a network of Mandarin instructors from Taiwan in exchange for Filipino English and Tagalog instructors.

Neither COVID nor Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte’s arbitrary and contradictory China policies will last forever, even if his daughter, currently favored in some polls to win the presidency, succeeds him. In anticipation of this, Taiwan needs to expand its military exchanges with the Philippines.

The government should also more strongly encourage Taiwanese firms to invest in Philippines. This may seem counterintuitive, but Taiwanese firms specialize in intermediate goods, often shipped to factories elsewhere in Asia for final shipment to Japan, Europe and North America or domestically. The Philippines should be more integrated into Taiwanese supply chains, especially as an alternative to China-based manufacturing. As part of its aid programs, Taiwan should be investing in upgrading the local electricity and Internet networks in the Philippines, to support increased investment and trade between the two nations.

The ghosts of our ancestors, who once traded across the local seas, would be proud.

Notes from Central Taiwan is a column written by long-term resident Michael Turton, who provides incisive commentary informed by three decades of living in and writing about his adoptive country.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the Taipei Times.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

With over 100 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of