May 17 to May 23

“Who still remembers Chan Yi-hua (詹益樺)?”

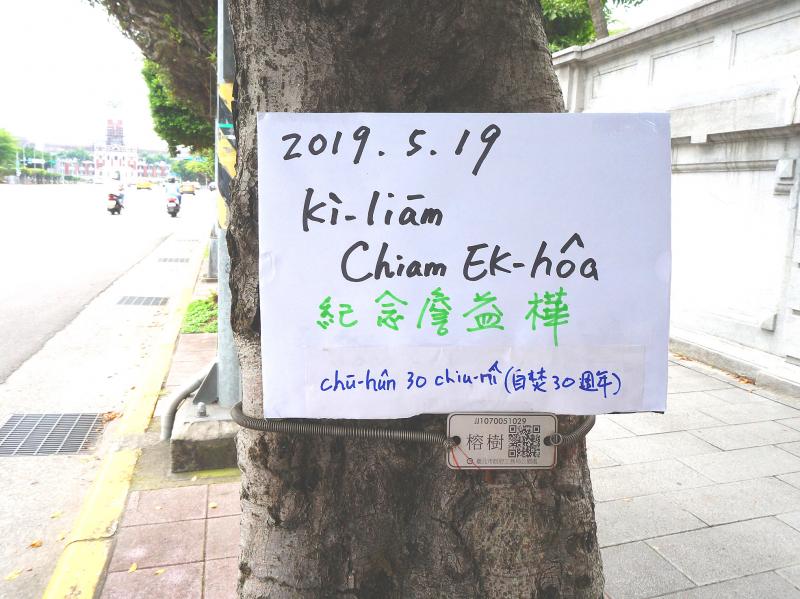

This question has been asked repeatedly over the decades, usually on the anniversary of Chan’s self-immolation on May 19, 1989 at fellow political activist Deng Nan-jung’s (鄭南榕) funeral in front of the Presidential Office.

Photo: Tsai Tsung-hsun, Taipei Times

Deng had committed the same act on April 7 when the police came to his office to arrest him for sedition. That day is now observed as National Freedom of Speech Day, and it would be pretty hard to find someone in Taiwan who doesn’t know Deng today.

The same can’t be said for Chan. His friend Chen Chen (陳真), who witnessed his death, asked the question in 2004 in a China Times Evening News (中時晚報) op-ed. Commentator Chang Chien-wu (張千舞) asked it again via the Liberty Times (自由時報, Taipei Times’ sister paper) in 2007, and both the Liberty Times and Taiwan People News (民報) brought it up again in 2016 on the 25th anniversary of his death.

It’s not that Chan has been completely forgotten — a statue of him has stood since 2007 in his hometown of Jhuci Township (竹崎鄉), Chiayi County, where people gather every May to remember him. His story was also a significant part of last year’s documentary The Price of Democracy (狂飆一夢), which featured his comrade Tseng Hsin-yi (曾心儀).

Photo: Tsai Tsung-hsun, Taipei Times

However, a search for Chan only yields one result in the National Central Library’s database: A-hua (阿樺), a collection of interviews and essays edited by Tseng. Chan’s activist career was brief but eventful. He first took to the streets during an anti-nuke protest in October 1986, and was severely beaten and detained a month later when trying to help the exiled politician Hsu Hsin-liang (許信良) enter the country.

Chan later delved into the farmer’s rights movement, and made a name for himself during a major clash with police on May 20, 1988, by tearing down the Legislative Yuan sign.

Deng’s death greatly affected Chan, who at one point worked for Deng’s publication Freedom Weekly. The day Deng died, Chan wrote in his diary, “I’d rather be with God than lead a life of submission under a pig trough.” It seemed like his mind was set. He was 32 years old.

Photo: Tsai Tsung-hsun, Taipei Times

LIFE-CHANGING EVENTS

Little is written about Chan’s early life. Human rights lawyer Kenneth Chiu (邱晃泉) writes in the Liberty Times in 2005 that he couldn’t find much: “After all, he was so young (when he died), and he wasn’t a well-known figure.”

Born in 1957, Chan never finished vocational school and held a number of odd jobs after he finished his military service. He was working as a deep-sea fisherman in 1985 when he fell overboard in an accident. He was rescued and stranded in Nelson, New Zealand for some time.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Chiu writes that in Nelson, Chan for the first time witnessed people “living with dignity,” a far cry from authoritarian Taiwan that had been under martial law since 1949. Coupled with his near-death experience, Chan began to change.

When he returned to Taiwan, he became involved in the dangwai (黨外, “outside the party”) opposition movement, handing out flyers during You Ching’s (尤清) campaign for Taipei County (today’s New Taipei City) commissioner.

Tsai Hai-pu (蔡海埔) recalls in A-hua Chan’s first protest, when anti-nuke marchers surrounded Taipower Building.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“He was barely noticeable, silently handing out flyers on the street corner. He walked behind the crowd and just sheepishly raised his shoulders when shouting slogans.”

The Democratic Progressive Party was illegally formed in September 1986, and exiled politician Hsu Hsin-liang made several attempts to return to Taiwan in November and December to participate. His supporters protested at the airport several times — and on the third attempt Chan was dragged to a military detention camp and severely tortured for nearly 10 hours before being dumped on the side of a road.

Those who knew Chan say that this incident completely changed his outlook and fully opened his eyes to the brutality of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) rule. He swore to never let this happen again, and wrote a final letter to show his determination.

Photo: Liu Wan-chun, Taipei Times

IN FLAMES

Chan was seen at almost every major protest over the next few years. Besides politics, he also championed labor, Aboriginal and farmer’s rights. He shed his initial timid image and was often seen walking in front of the crowd, yelling into a loudspeaker.

Chan was working with Tai Chen-yao (戴振耀) in organizing grassroots farmer’s movements in rural Kaohsiung when news of Deng’s death broke. He left for Taipei immediately to prepare for the funeral, which would take the form of a massive protest.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The police unleashed water cannons at the crowd when they reached the Presidential Office. At that moment, Chan suddenly doused himself with gasoline, which he had hidden in his jacket. The first lighter didn’t ignite, so he tried a second — and with the flames engulfing his body, he threw himself against the wire barricades the police set up.

“I will never forget those roaring flames,” Chen Chen writes .”He was still holding the lighter, and blood was pouring out of his burning head, which was pierced by razor wire. But his expression was peaceful; it was as if he was just sleeping.”

Those who visit Chan’s memorial every year see him as a great martyr who gave his life for Taiwan and its democracy. But why do people still keep asking, “Who still remembers Chan Yi-hua?”

Chang and others write that compared to Deng, Chan was a “nobody” who came from the bottom rungs of society. He rarely made speeches, and left little writings behind and remained just an everyday grassroots activist until his tragic end.

Nobody should be encouraging the act of self-immolation, but it is important to reflect on the circumstances that would push activists in those days towards such actions, and remember the price these people paid for the democracy we enjoy today.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name

There is no question that Tyrannosaurus rex got big. In fact, this fearsome dinosaur may have been Earth’s most massive land predator of all time. But the question of how quickly T. rex achieved its maximum size has been a matter of debate. A new study examining bone tissue microstructure in the leg bones of 17 fossil specimens concludes that Tyrannosaurus took about 40 years to reach its maximum size of roughly 8 tons, some 15 years more than previously estimated. As part of the study, the researchers identified previously unknown growth marks in these bones that could be seen only