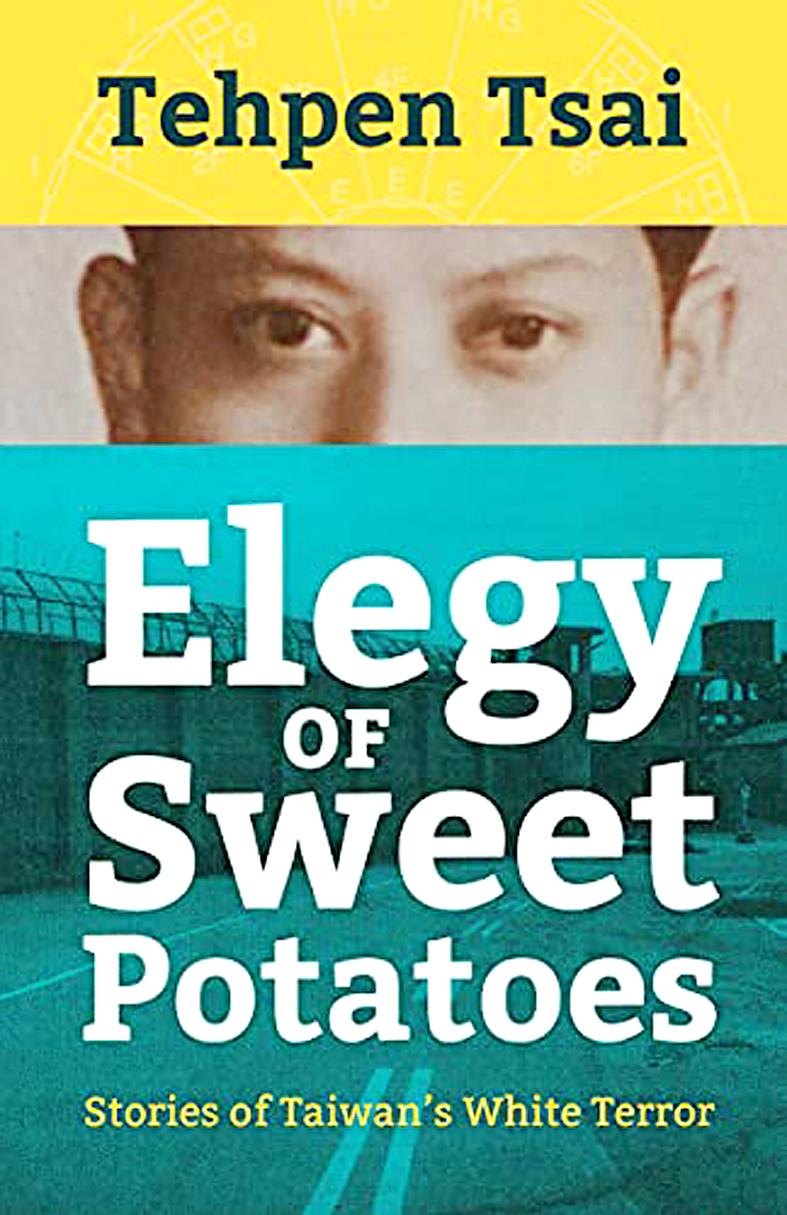

Prison books are a semi-major literary genre. Works such as Solzhenitsyn’s The First Circle, flanked by One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, are classics, with Dickens, Genet and Nelson Mandela also featuring. Most of them are at least partly autobiographical, and Tehpen Tsai’s (蔡德本) Taiwan White Terror novel, Elegy of Sweet Potatoes, is no exception.

It was originally written in Japanese (Tsai was brought up during Japan’s occupation of Taiwan), then translated into Chinese. An English version, finely crafted by Grace Tsai Hatch, appeared in 1995 and now re-appears from Taiwan’s Camphor Press. The author, who helped with the translation, was her uncle.

Initially set in 1954, it’s the story of Youde, a middle-school teacher in Chiayi, who is arrested and, on the evidence of alledgedly having a book written by Mao Zedong (毛澤東), is accused of being a Communist. He is held for over a year, in Chiayi, Taipei and elsewhere.

Youde was born in 1925 in Chiayi County’s Putzu City (朴子). He went, as did Tsai, to the US for a year on a scholarship after graduating from university, and returned to teach in his home town.

The least that could happen to him, a fellow prisoner thought, was that he would be sentenced to three years of “re-education without crime,” though a “workplace guarantee” was also possible, whereby an employer would guarantee his good-conduct, while his behavior was scrutinized. But the terrifying dictum of then-president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) was generally observed: Do not let one escape even if 100 are mistakenly killed.

In Chapter 39, Tsai writes that when Taiwan was first placed under Chinese rule in 1945, only Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) members were permitted to move here. Some Communists nonetheless joined the KMT as a cover and proceeded to infiltrate schools and offices and recruit for the Party. If discovered — and eight or nine out of 10, the author estimates, were — they were invariably sentenced to death. He adds that, contrary to popular belief, many former Mainlanders were arrested for political crimes, possibly more than local Taiwanese.

Of a doctor recently returned to Taiwan, Youde (i.e. Tsai) comments that “he had mistaken the foreign regime” — i.e. the KMT — “that landed on Taiwan’s shore as the government of his country.”

This doctor was also noted as having been away from Taiwan during the 228 Incident and its aftermath, and consequently “did not get the immunization shots against the reign of the White Terror.”

We learn that back in the 1950s the White Terror was never reported on in the local newspapers, which were all KMT-owned. Nor was it mentioned in letters; people knew too well the likely consequences of that.

There are many memorable prisoners in this book, almost all sympathetically portrayed. The teenager Ah-fu, for example, is presented as a delightful soul, even though he killed two gambling mates. The characters of the various interrogators are also presented with considerable subtlety. Some are not unkind (one is called “gentlemanly”) and are themselves “sweet potatoes,” a term meaning Hoklo-speaking Taiwanese.

Many impressions linger in the mind from this exceptional book. Horrific torture on Green Island, singing prisoners, thumbprints placed at the end of reports on interrogations and two men kneeling in the sand of the execution yard at Hsintien, are just a few. No female prisoners are depicted.

It’s also noted that public servants at the time were organized in groups of three or five with everyone in the group responsible for the conformity of the others. This, the author states, is similar to the “mutual responsibility law” in 16th century China. And so it is you come to understand that instruments of government control have a long history, and even governments are careful to comply with what they see as the law. In Shakespeare’s day, anyone charged in England had to make a plea, and thereby recognize the authority of the court. Torture, notably the rack, would be used to produce a plea if necessary.

Youde is next taken from Chiayi to what he describes as “the Devil’s Palace of Chingtao East Road” in Taipei, a court from which prisoners condemned to death (many thousands of them) were taken direct to the execution ground. Fresh air, sunshine and cold water became the best things in life for all prisoners — that, and the food they receive.

Taken almost at random, we learn of one fellow prisoner who was arrested on account of five words he wrote on a slip of paper. Another is charged because he tried to mend a cracked pane of glass with stickers in the shape of a star, perceived as being a reference to the Chinese Communist Party. For this “crime” he received 10 years’ imprisonment.

All death sentences for political crimes required the president’s signature, and Youde contemplates the fact that from 1949 onwards Chiang must have signed up to 10 such documents every day.

We learn alot about the White Terror — the various charges that were brought against suspects, conditions in the different security-related prisons and the slang terms used by prisoners for implicating others as a way of, hopefully, getting one’s own sentence reduced.

Death looms large. When special guards arrive at a prison to take away some inmates for execution, the prisoners immediately know how many of their number will be taken as the ratio of two guards per condemned man is invariably observed.

All in all, this is the best book of any kind, fiction or non-fiction, that I’ve ever come across on the White Terror. Nobody reading it could possibly come away unmoved or anything but better informed. Of course, we know from the start that Youde/Tsai will eventually be released because how else could a book like this have been written? But there are plenty of other memorable characters whose fates hang in the balance.

Tehpen Tsai doesn’t go out of his way to depict himself as a truthful and congenial character, but that’s what he undoubtedly was. Sadly, he died in 2015, in Tainan, aged 89. In this slightly fictionalized account Youde is portrayed as starting to write his book in 1991, at 66 years of age.

Most heroes are remembered for the battles they fought. Taiwan’s Black Bat Squadron is remembered for flying into Chinese airspace 838 times between 1953 and 1967, and for the 148 men whose sacrifice bought the intelligence that kept Taiwan secure. Two-thirds of the squadron died carrying out missions most people wouldn’t learn about for another 40 years. The squadron lost 15 aircraft and 148 crew members over those 14 years, making it the deadliest unit in Taiwan’s military history by casualty rate. They flew at night, often at low altitudes, straight into some of the most heavily defended airspace in Asia.

Beijing’s ironic, abusive tantrums aimed at Japan since Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi publicly stated that a Taiwan contingency would be an existential crisis for Japan, have revealed for all the world to see that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) lusts after Okinawa. We all owe Takaichi a debt of thanks for getting the PRC to make that public. The PRC and its netizens, taking their cue from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), are presenting Okinawa by mirroring the claims about Taiwan. Official PRC propaganda organs began to wax lyrical about Okinawa’s “unsettled status” beginning last month. A Global

Taiwan’s democracy is at risk. Be very alarmed. This is not a drill. The current constitutional crisis progressed slowly, then suddenly. Political tensions, partisan hostility and emotions are all running high right when cool heads and calm negotiation are most needed. Oxford defines brinkmanship as: “The art or practice of pursuing a dangerous policy to the limits of safety before stopping, especially in politics.” It says the term comes from a quote from a 1956 Cold War interview with then-American Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, when he said: ‘The ability to get to the verge without getting into the war is

Like much in the world today, theater has experienced major disruptions over the six years since COVID-19. The pandemic, the war in Ukraine and social media have created a new normal of geopolitical and information uncertainty, and the performing arts are not immune to these effects. “Ten years ago people wanted to come to the theater to engage with important issues, but now the Internet allows them to engage with those issues powerfully and immediately,” said Faith Tan, programming director of the Esplanade in Singapore, speaking last week in Japan. “One reaction to unpredictability has been a renewed emphasis on