May 10 to May 16

Many elderly people wept as the crowds flooded Raohe Street (饒河街) on May 11, 1987.

It had been over a decade since the street was this busy, the Minsheng Daily (民生報) reported. Locals set up altars along the way, praying that the grand opening of the Raohe Street Night Market would reverse their fortunes.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

It was Taipei’s first night market with government-mandated traffic control hours, banning cars from 5pm to midnight.

“This is a great way to manage a night market, and other locales should follow suit,” the article stated.

There were still some kinks to iron out. Vendors who illegally occupied vehicle lanes near the Songshan Bridge mostly refused to relocate to the night market. The Taipei City Government gave them 15 days to comply.

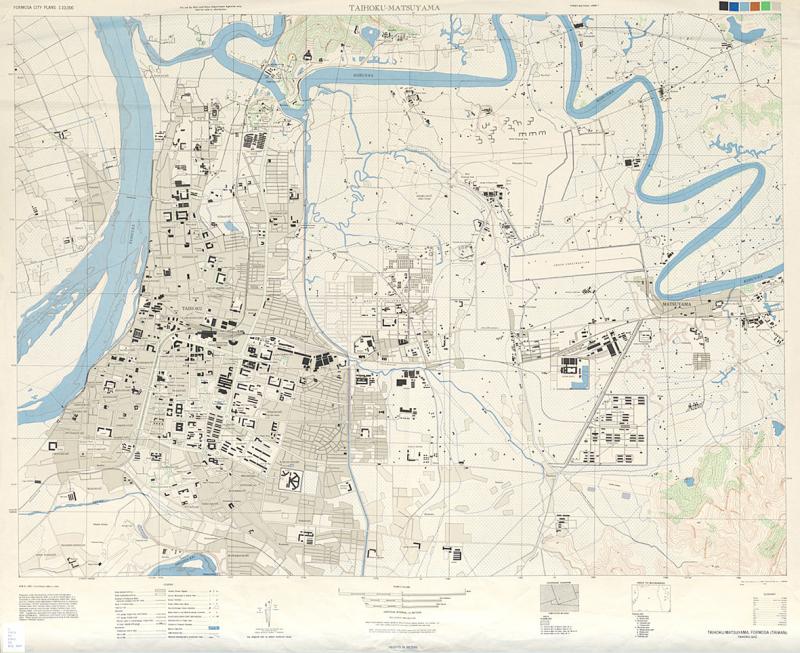

Photo courtesy of Open Museum

Known as Xikou (錫口) during the Qing Dynasty, the area surrounding Raohe Street was one of Taipei’s wealthiest neighborhoods. There was no road to the Dadaocheng (大稻埕) area or Wanhua District (萬華) in the western part of the city, and the only way to get there was to catch a boat from Xikou Wharf. The area lost much of its former glory after the railroad was completed in 1891, but remained a notable business district until a street-widening project in 1975 led to a sharp decline.

The revitalization plan worked, and today Raohe Street Night Market remains one of the most popular of its kind in Taipei. Coupled with the completion of the pedestrian-only Rainbow Bridge and adjacent riverside bikeway, the area is now teeming with activity at night and on the weekends.

PROSPEROUS STREET

Photo courtesy of Cyber Island

According to the book Gazetteer of Old Songshan (古松山方志) by Wang Shou-ning (王受寧), the Xikou area boasted some of the largest Aboriginal settlements in the Taipei basin during the 1600s. The one near Raohe Street was called Malysyakkaw; Han settlers called it Maolixikou (貓裡錫口) and shortened it to Xikou after they displaced the indigenous population in the late 1700s. The area to the south around today’s Songshan Station was part of a vast field where locals hunted deer.

Malysyakkaw residents were among the earliest Catholic converts in Taipei. Spanish missionaries in 1626 passed by their community via the Keelung River on their way to Tamsui and reportedly got along with them well; the Europeans would find much less success in Tamsui, where relations were rocky and often violent.

By the 1700s, Xikou had become a bustling market and port centered around Raohe Street. An old saying reveals that the eastern end of street was Catholic, the western end was Protestant (courtesy of famed Canadian missionary George Leslie Mackay, who built a church there), and the middle was dominated by a local gangster named Chen Chao-ming (陳朝鳴).

Ciyou Temple (慈祐宮) was completed in 1757, and when Chinese traveler Yu Yong-he (郁永河) visited the street that year, he noted that there were both Aboriginal and Han inhabitants. The Aborigines were eventually forced out as Han settlers poured in, many of them moving to today’s Sijhih District (汐止) in New Taipei City.

Those who remained assimilated into Han culture, and by the time the Xikou Courier Station was established in 1815, the area was dominated by the new migrants. Nicknamed “Little Suzhou,” Xikou remained one of Taipei’s most prosperous areas until the mid-1800s, when members of the wealthy Tu (杜) family began moving to Dadaocheng in the west.

In addition to the completion of the railroad, the wharf’s function further declined due to the build up of river sediment.

FALL AND REVIVAL

As a major railroad station, however, Xikou benefited from the gold rush in Jiufen (九份) and Jinguashi (金瓜石) on Taiwan’s northern coast during the 1890s, and there were reportedly 20 gold jewelry shops on Raohe Street alone.

In 1896, a year after Taiwan became a colony of Japan, a local named Chan Chen (詹振) rallied 600 men and rose up against the colonizers, killing 20 Japanese railroad workers, burning a mansion belonging to the Japanese-friendly Chen Chun-kuang (陳春光) and damaging the railroad. Chan was killed, and the Japanese torched nearly two-thirds of the area’s traditional buildings as punishment. Chen was appointed district chief of Xikou in the aftermath.

The area was renamed Matsuyama (Songshan in Chinese) during a rezoning of Taipei in 1920, and Chen Chun-kuang’s nephew Chen Mao-sung (陳茂松) was appointed district chief at the age of 26. It was surprising as the Japanese never appointed anyone under the age of 30 to such positions. Chen Mao-sung reportedly spent more than half of the family fortune renovating the Ciyou Temple.

During the Japanese era, most residents on Raohe Street were regular workers employed at the railroad or the nearby tobacco factory (today’s Songshan Creative and Cultural Park). A notable disaster took place in 1938 when Chinese warplanes attempted to bomb an armory in the area but accidentally struck residences at the corner of Raohe Street and Nanjing E Road (南京東路), killing over 20 Taiwanese.

Xikou Street was renamed Raohe Street after World War II. While still a commercial center in eastern Taipei, it was being increasingly overshadowed by rapid development in nearby areas. Many businesses relocated during a street-widening project in 1975 and never moved back, and soon it could no longer compete with the neighboring Bade Road (八德路), which was also greatly expanded.

The popularity of Ciyou Temple once attracted many street vendors to the area, but an increase in cars due to the newly-widened street led to diminished foot traffic, and even these vendors began moving away. For the next decade, Raohe Street barely saw any commercial activity.

Locals were desperate to revive the street, and the government also wanted to better manage the illegal vendors, who were now scattered around the area and occupying public lanes. Both problems would be solved by establishing a night market in the area, and the two sides began working in the early 1980s to make that happen.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

With over 80 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of