April 26 to May 2

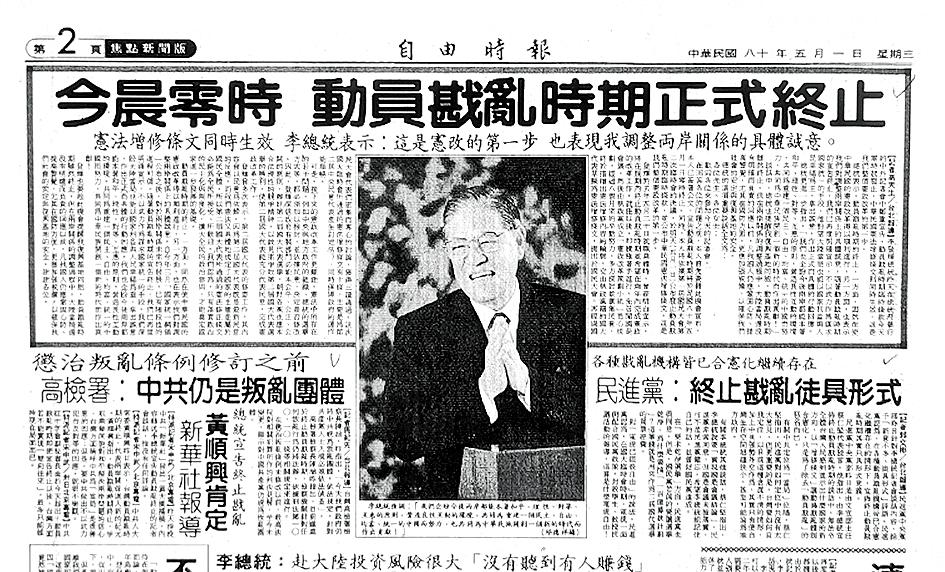

Although the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) had essentially given up retaking China by the late 1960s, they continued to espouse the notion until former president Lee Teng-hui (李登輝) declared in a press conference on April 30, 1991: “We will no longer seek to unify China through force.”

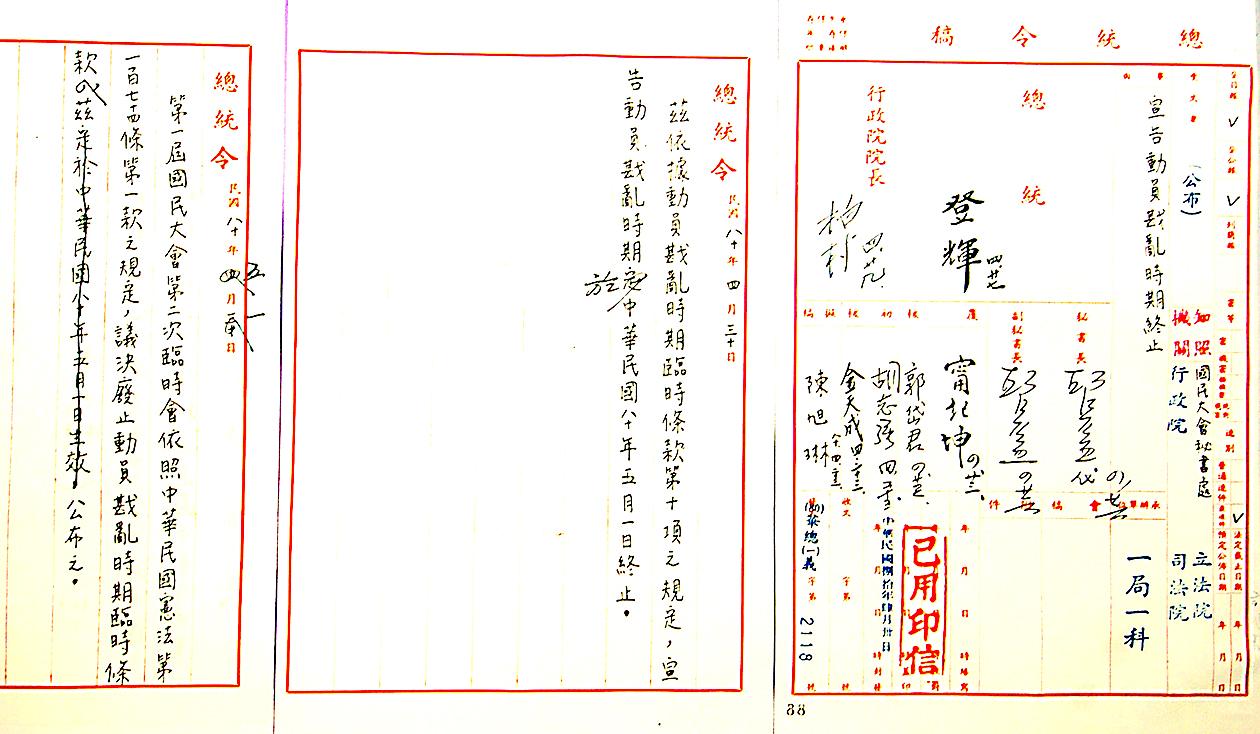

Lee was announcing the repeal of the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of National Mobilization for Suppression of the Communist Rebellion (動員戡亂時期臨時條款, temporary provisions for short), which had allowed the government to rule with an iron fist for nearly 43 years without following the Constitution.

Photo: Tang Chia-ling, Taipei Times

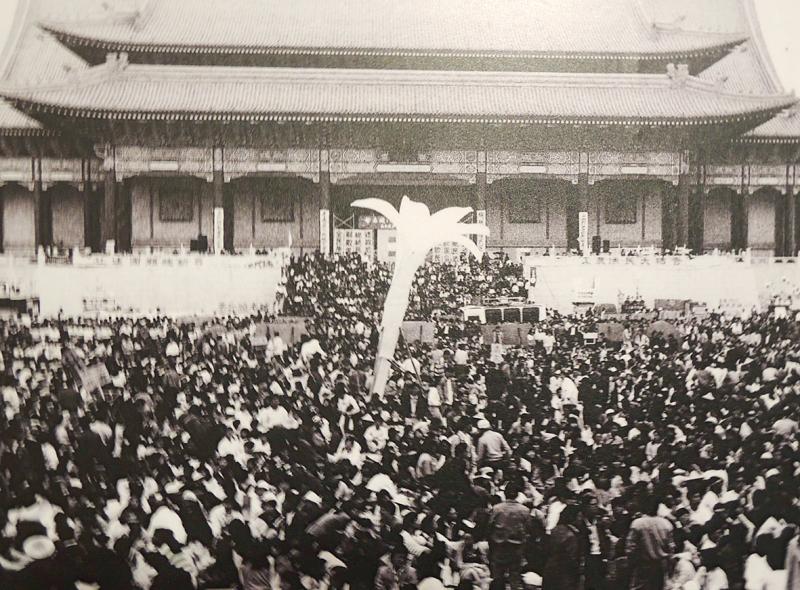

Although martial law was lifted in 1987, the provisions remained in place and their abolishment was one of the main demands for democracy activists, including the thousands of students who gathered in March 1990 at Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall in what would be known as the Wild Lily student movement.

Democracy activist Deng Nan-jung (鄭南榕) wrote in the December 1988 edition of his magazine Freedom Era Weekly that the temporary provisions “suffocated Taiwan’s political system … and is the source of all chaos in Taiwanese politics.”

Deng never got to see the hated law scrapped. The authorities charged him with sedition and he self-immolated on April 7, 1989 when the police came to his office to arrest him. This only showed that, even though martial law had been lifted, the White Terror continued.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

On the sixth day of the student movement, Lee met with the protest leaders and heard their demands. In June, he convened a national affairs conference, where among other items, the representatives decided to put an end to the temporary provisions and return to full constitutional rule.

A Liberty Times (Taipei Times’ sister paper) editorial stated, “It is hard to believe that two-thirds of the 2 million people in Taiwan have lived their entire life under the cloud of the [temporary provisions]. There is no need to celebrate, however. When our descendants ask us how we were able to stand this monster for so long, we can only hang our heads in shame.”

INDEFINITE EMERGENCY

Photo: Liao Chen-hui, Taipei Times

The Chinese Civil War was raging in July 1947 when former president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) announced the Period of Mobilization for the Suppression of Communist Rebellion to “save the people in the liberated areas, ensure the survival of our people, strengthen the unity of our country and suppress the Chinese Communist Party in order to achieve constitutional rule on schedule.”

The Constitution, which was promulgated in January 1947, went into effect on Dec. 25. As the situation worsened, the KMT wanted to expand Chiang’s power but felt that amending the Constitution so quickly would be unpopular. After deliberating, they decided to add the temporary provisions, which were adopted on May 10, 1948 and set to expire two years later.

Wang Shih-chieh (王世杰), one of the National Assembly members who proposed the temporary provisions, wrote, “If the government is bound to the Constitution, it won’t be able to react to the nation’s immediate needs to suppress the rebellion … But if we change the Constitution now, the people will think we are disrespecting the law. Our proposed act is temporary, once the rebellion is suppressed, it will expire.”

Taipei Times file photo

The KMT retreated to Taiwan in 1949, but they refused to admit defeat and continued to see the CCP as a rebel group. Thus, the temporary provisions remained in place and were extended indefinitely in 1954.

They continued to provide the basis for martial law, White Terror, one-party rule and indefinite presidential terms for Chiang.

It was amended three times over the following decade, with each amendment granting Chiang more privileges under the pretense of wartime emergency.

Chiang’s last serious attempt to invade China failed to materialize in 1965, but he clutched onto his emergency powers until his death in 1975. After the lifting of martial law, protests against the KMT exploded and continued to intensify — two large-scale events rocked the capital in the month leading up to Lee’s announcement.

NEW RELATIONSHIP

Not everybody supported repealing the temporary provisions, especially unificationists. A 1988 article in the magazine Journal of Sunyatsenism (三民主義學報) claims that the laws “contributed invaluably to ensuring the stability of our base to retake China,” and that it has provided flexibility to deal with the “division of the country.”

To them, the war was still going on and repealing the provisions were not suited for these “emergency times” — only that the emergency had lasted for four decades with no resolution in sight. Most importantly, with the repeal of the temporary provisions, the Chinese Communist Party would no longer be seen as a rebel group.

“From now on, we will see the Chinese Communist Party as a political entity that controls the mainland region and we will call them the ‘mainland authorities’ or the ‘Chinese Communist authorities,” Lee said during the press conference, and referred to then-Chinese leader Yang Shangkun (楊尚昆) as “Chairman Yang.” Lee also acknowledged the independence of Mongolia, which the KMT continued to claim over the decades.

Reporters had many questions about this new relationship. Would Lee visit China in the future?

“If they invite me over as the president of the Republic of China, I think I would give it a try,” he replied.

However, Lee spoke against Chinese psychological warfare to “divide the people of Taiwan” and noted that the Straits Exchange Foundation would remain the sole official contact point with Beijing, who continued to threaten Taiwan and marginalize it internationally.

The People’s Daily , the CCP’s main mouthpiece, welcomed the move, calling for both sides to establish direct flights, mail and trade. It would take 12 more years for the first cross-strait charter plane to leave Taiwan.

Another effect of the repeal is that temporary martial law was declared on May 1, 1991 in Kinmen and Matsu, which were administered as war zones. This was lifted, along with the war zone designation, the following November. in January, went into effect on Dec. 25. As the situation worsened, the KMT wanted to expand Chiang’s power but felt that amending the Constitution so quickly would negatively affect popular sentiment. After deliberation, they decided to add the temporary provisions, which were adopted on May 10, 1948 and set to expire after two years.

The KMT lost the war and retreated to Taiwan in 1949, but the provisions remained. They were extended indefinitely in 1954, and continued to provide the basis for martial law, White Terror, one-party rule and indefinite presidential terms for Chiang.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

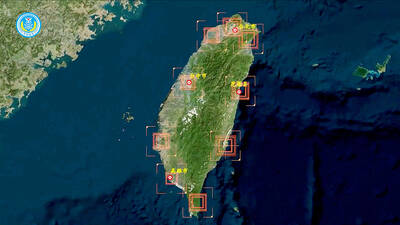

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) last week offered us a glimpse of the violence it plans against Taiwan, with two days of blockade drills conducted around the nation and live-fire exercises not far away in the East China Sea. The PRC said it had practiced hitting “simulated targets of key ports and energy facilities.” Taiwan confirmed on Thursday that PRC Coast Guard ships were directed by the its Eastern Theater Command, meaning that they are assumed to be military assets in a confrontation. Because of this, the number of assets available to the PRC navy is far, far bigger

The 1990s were a turbulent time for the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) patronage factions. For a look at how they formed, check out the March 2 “Deep Dives.” In the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s the factions amassed fortunes from corruption, access to the levers of local government and prime access to property. They also moved into industries like construction and the gravel business, devastating river ecosystems while the governments they controlled looked the other way. By this period, the factions had largely carved out geographical feifdoms in the local jurisdictions the national KMT restrained them to. For example,

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of

Shunxian Temple (順賢宮) is luxurious. Massive, exquisitely ornamented, in pristine condition and yet varnished by the passing of time. General manager Huang Wen-jeng (黃文正) points to a ceiling in a little anteroom: a splendid painting of a tiger stares at us from above. Wherever you walk, his eyes seem riveted on you. “When you pray or when you tribute money, he is still there, looking at you,” he says. But the tiger isn’t threatening — indeed, it’s there to protect locals. Not that they may need it because Neimen District (內門) in Kaohsiung has a martial tradition dating back centuries. On