April 12 to April 18

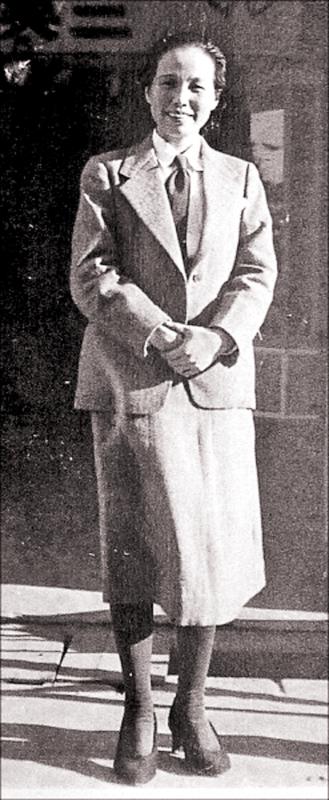

Hsieh Hsueh-hung (謝雪紅) stuffed her suitcase with Japanese toys and celebrity photos as she departed from Tokyo in February 1928. She knew she would be inspected by Japanese custom officials upon arrival in Shanghai, and hoped that the items would distract them from the papers hidden in her clothes.

Penned with invisible ink on thin sheets, it was the charter of the Taiwanese Communist Party (台灣共產黨, TCP), which Hsieh and her companions would launch on April 15 under the directive of the Soviet-led Communist International with the support of their Chinese, Japanese and Korean counterparts.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The ruse worked. The young and homesick Japanese inspector stared longingly at the photos, upon which Hsieh said, “You can have these if you want.” She was cleared immediately.

The short-lived party was ill-fated from the very start. Just 10 days after its formation, the Japanese police raided its headquarters in the French Concession, arresting several members, including Hsieh, and confiscated the charter.

The TCP later regrouped in Taiwan and continued their mission, but it was plagued by factionalism and government suppression. In June 1931, having finally obtained the list of members, the Japanese authorities launched a massive crackdown on the party, essentially destroying it within a few months. A total of 49 people were convicted.

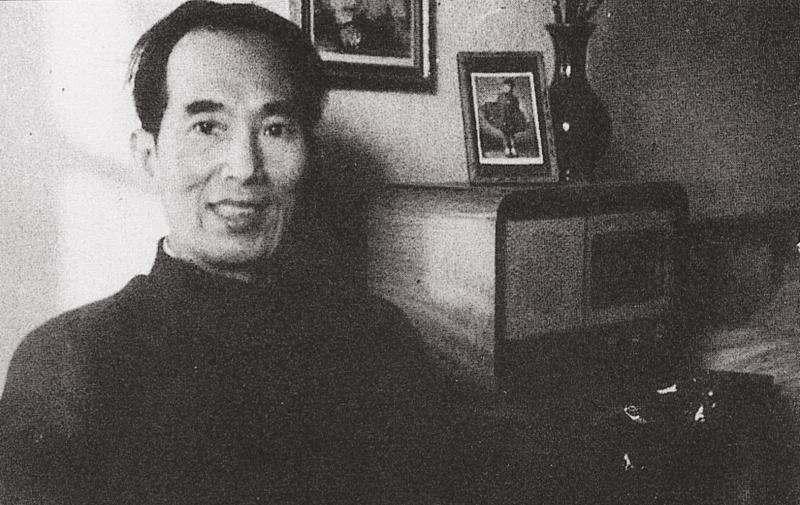

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

IMPORTANT MISSION

After training for nearly two years at the Communist University of the Toilers of the East in Moscow, whose alumni include Deng Xiaoping (鄧小平), Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國) and Ho Chi Minh, Hsieh and classmate Lin Mu-shun (林木順) departed for Shanghai on Nov. 13, 1927 with big plans.

A month earlier, Japanese Communist Party (JCP) cofounder Sen Katayama approached Hsieh and Lin on behalf of the Communist International and tasked them with launching the TCP. Hsieh was to lead the operation with Lin assisting, and the JCP providing guidance. Katayama wanted them to visit Shanghai to contact the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which was being attacked by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), and recruit like-minded Taiwanese to the cause. Then they would head to Tokyo to meet with JCP’s top brass.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Through Lin’s brother, the two met Weng Tze-sheng (翁澤生), a Taiwanese who joined the CCP in 1926 and lost contact with the organization after the KMT’s communist purge in 1927. Weng remained in contact with a number of Taiwanese leftists and launched a youth reading group on behalf of Communist International while Hsieh and Lin went on to Japan.

The JCP was outlawed in Japan in 1925, and Hsieh and Lin secretly met with its members while making contact with Taiwanese. With the help of JCP officials, they drafted their charter, which included Taiwanese independence in the name of anti-imperialism, and returned to Shanghai.

Weng had by then recruited more members from Taiwan and other parts of China, and received assistance from Korean Communist International member Lyuh Woon-hyung. There seems to be much personal drama in the following months, and Hsieh does not speak kindly of Weng in her autobiography. In March 1928, the Japanese police raided the reading group’s headquarters and arrested three members, although they did not find any vital documents.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

On April 13, Hsieh and Lin met with CCP official Peng Jung (彭榮, using a false name with his real identity unclear), who approved their charter.

Peng and Lyuh presided over the founding ceremony, which took place in the morning of April 15 at a mansion in a remote corner of the French Concession. There were 18 founding members. At their first meeting a few days later, they decided that Hsieh and Chen Lai-wang (陳來旺) would head to Japan, Weng would remain in China and the rest would return to Taiwan to carry out the revolution.

ARRESTS AND INFIGHTING

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The plan never came to fruition as the Japanese raided the headquarters and deported the arrested to Taiwan. Six members were jailed, but Hsieh was acquitted due to a lack of evidence. Lin escaped, and continued supporting the TCP from Japan and China.

Hsieh got to work immediately and worked closely with the farmers’ rights movement, earning another brief detainment during a crackdown on the Taiwan Peasants Union on Feb. 12, 1929. Hsieh writes that the TCP was the real target, but the authorities failed to find solid evidence to link the two organizations. Several members fled to China after the incident while several more quit.

By 1931, the party had essentially split into two factions. Hsieh’s group believed in including the middle class (who made up the bulk of anti-Japanese resistance) in the revolution and operating covertly since they were watched by police, while Weng and others wanted her to increase the party’s membership drive and actively launch a public class struggle.

The JCP that supported Hsieh was rendered inactive after the government launched a mass raid against its members in March 1928, while the CCP urged Weng’s faction to convince Hsieh to change her ways.

In May, Weng’s faction ousted Hsieh from the party. But the end was near. Two months earlier, the Japanese arrested two members and finally acquired the vital documents they had been seeking. They now knew exactly who to go after.

Hsieh was nabbed in June. “My job is the communist movement,” she told prosecutors when asked about her profession

At the time, Weng was in China, trying to carry on with party activities. But he was caught by the KMT in Shanghai and handed over to the Japanese in 1933, who took him back to Taiwan to stand trial.

Lin was also in China, but he evaded capture and was never heard from again. Various sources indicate that he died fighting the KMT in the short-lived Chinese Soviet Republic.

A total of 49 people tied to the party were convicted on June 30, 1934 and sentenced to between two and 13 years in jail. After years of torture and mistreatment, both Hsieh and Weng were in bad shape. Weng was released due to illness in March 1939, and died shortly after.

Hsieh was also released early in April 1940, and kept a low profile before leading an armed resistance against the KMT during the aftermath of the 228 Incident, an anti-government uprising that was brutally suppressed. She fled to China afterward and never returned to Taiwan

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.

It’s a bold filmmaking choice to have a countdown clock on the screen for most of your movie. In the best-case scenario for a movie like Mercy, in which a Los Angeles detective has to prove his innocence to an artificial intelligence judge within said time limit, it heightens the tension. Who hasn’t gotten sweaty palms in, say, a Mission: Impossible movie when the bomb is ticking down and Tom Cruise still hasn’t cleared the building? Why not just extend it for the duration? Perhaps in a better movie it might have worked. Sadly in Mercy, it’s an ever-present reminder of just

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of