In the winter and early spring of 1940, Nazi Germany found itself facing a problem that had plagued Germany in World War I: growing food problems and lack of access to raw materials. The conquests of 1939-40, while bringing in much valuable booty, simply added millions more mouths to feed. Europe, as the Germans came to realize, had no spare food capacity.

England had refused to either make peace or ally with Germany as Hitler had expected, and its blockade meant that Germany was absolutely dependent on imports of food and war materials from Soviet Russia to stay in the war. Indeed, the longer the war went on, the greater the implications of this dependency: Germany’s demand for Russian supplies could only grow. Stalin demonstrated his power over Germany by temporarily suspending oil and grain exports to Germany shortly before the offensive in the west.

Faced with this dependency on imports from Russia, and haunted by the fears of food shortages that had broken Germany in the World War I, Hitler and his top officials accelerated their plans to attack Russia and seize its resources and agricultural lands. This policy became ever more urgent since Germany would never be able to face the US and the UK without them, German planners felt.

Photo: Bloomberg

The policy of attacking Russia was pursued despite warnings from military staff studies and high-ranking officers that Germany could not win a war against Russia (eventually planners began shading their conclusions to please Hitler) and even if it did, the short-term gains would not justify the costs of war, while Germany lacked the requisite capital and machinery to develop Russian agricultural lands. It would be years before they would become productive. Hitler’s obsessive desire to obtain those resources and stave off food shortages overruled reality. Thus, instead of protecting Russia, Germany’s dependency on Soviet grain ultimately helped condemn the USSR to invasion from Germany.

Across the earth Japan, buried up to its waist in China, faced a similar problem. Japan was completely dependent on imports of oil, metals and advanced machine tools from the US to make and operate the weapons it needed to conquer China. It also drew on raw materials from the eastern colonies of the European powers. This dependency meant that the western powers had a veto over its war in China: it could continue only as long as the US supplied the oil (metals and machine tools were cut off by 1940). Japan thus looked with longing at the colonies of European nations in Asia, rich in oil, food and other materials of war. The hold that Europe and the US held over the flow of raw materials to Japan simply increased the urgency of war for Japanese planners.

HIGH STAKES GAMBLE

Photo: Reuters

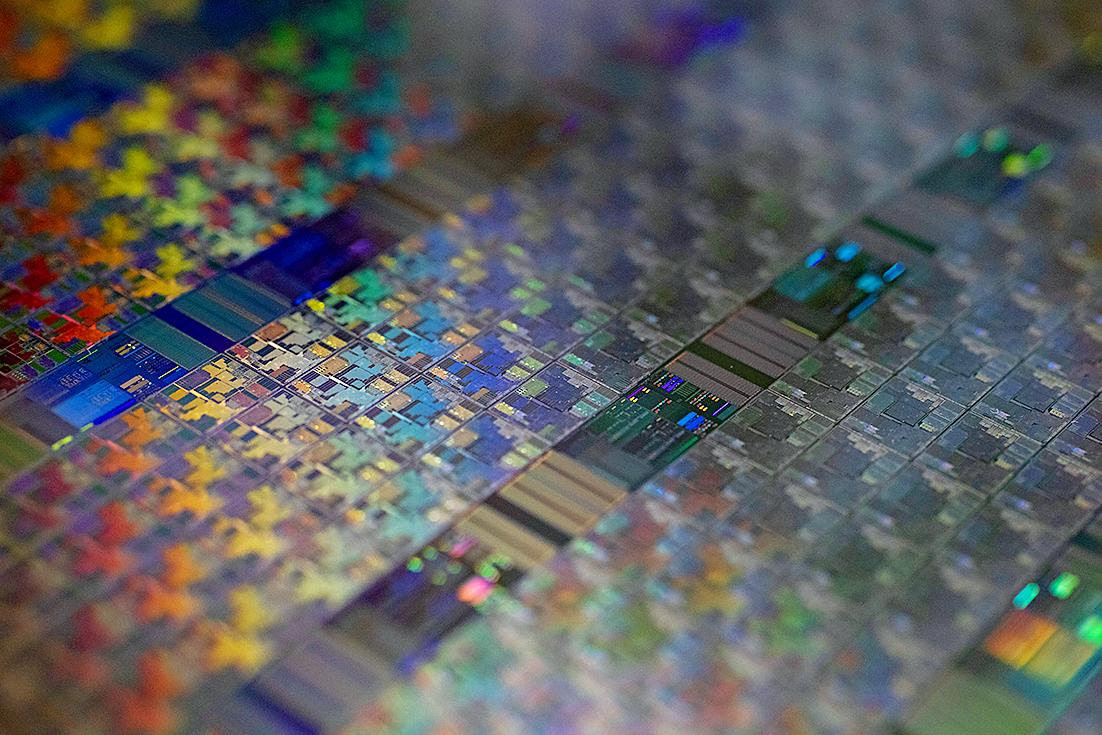

These cases are rather dramatic, but they illustrate a key point: an economic dependency on states that expansionist nations already covet simply exacerbates their desire to grab its territories. Writers and thinkers on Taiwan-China issues have been floating the idea that China’s dependency on semiconductor giant Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation (TSMC) can prevent it from attacking Taiwan. History implies the opposite: dependency will only make Beijing’s desire for Taiwan stronger and its problems appear more urgent, inviting high stakes gambles to solve them.

Today TSMC makes 70 percent or so of the world’s high-grade semiconductors, used in millions of different products. For example, a modern car might have around 3,000 semiconductors aboard. Thus, the current semiconductor famine is so severe it has forced global carmakers to idle or shut down factories. The ceaseless growth in the demand for semiconductors may be a boon to makers, but what does it mean for Taiwan-China relations?

Fundamentally, a nation facing a dependency on another nation for a critical good has only a few choices. It can alter its economy so the good is no longer critical, it can develop new sources, it can manufacture the good itself or it can conquer the holder of the resource. China is pursuing both the latter two approaches through its Vision 2035 strategy, which calls for semiconductor manufacturing, and its plans to annex Taiwan.

Photo: Reuters

That last approach is as old as geostrategy. Recall that the Romans, dependent on grain imports, stripped Carthage of its grain-producing territories of Sardinia, Sicily and finally North Africa itself in successive victories in the Punic Wars. Thousands of Romans were then settled in North Africa to produce grain.

Dependence on Ottoman middlemen, after all, drove the Europeans around Africa and into the Pacific, searching for a way to bypass the Islamic states to obtain the riches of the East via colonization. Trade may make for friendly relations according to political scientists, but history teaches that dependency drives desire.

China’s dependency will only grow since it needs semiconductors for an endless range of applications, from smart appliances to its growing military. That will merely make taking Taiwan more important. There is even a sweetener: if TSMC’s production were destroyed, that would affect China’s rivals, the EU and the US, just as much, if not more, than China. Further, when production finally resumed, China would control it all.

Photo: Bloomberg

IRRATIONALITY

Bound up with the whole dependency issue is the idea of human rationality. Arguments that Beijing will recognize its dependencies and refrain from war assume that Beijing will be rational. But that is hardly the case in the real world. China’s desire for Taiwan is entirely irrational: if China treated Taiwan as just another nation instead of irrationally demanding to annex Taiwan and plunge Asia into war, it could have all the semiconductors it wanted from Taiwan.

Even in the case of successful conquest of Taiwan, Beijing will face the same problem Germany did with Russia: Taiwan imports most of its food, including almost all its edible oils. China itself is already a major importer of food and energy. Taking Taiwan will not solve China’s problems of food and energy imports. It will add another restive possession to the empire that requires immense investments in security and population control, while worsening China’s food and energy dependence problems, which China will have to deal with even as submarines of the US and its allies are hunting down Chinese merchant ships.

Chinese planners, of course, are well aware of these things. Just as Imperial Japanese planners were aware of the immense advantages of the US over Japan in a war. Just as Nazi German planners knew the USSR was unconquerable. Just as the Confederacy knew of the North’s great industrial might (British industry’s dependence on southern cotton was countered by its workers’ dependence on northern wheat). Just as the Boers knew they faced the greatest power on earth in 1899.

Rational assessment did not stop these governments, and numerous other leaders, who argued that they had moral or racial superiority that would offset the other side’s material strengths, from entering into armed conflicts that ended in catastrophic defeats.

It will not stop China either.

Notes from Central Taiwan is a column written by long-term resident Michael Turton, who provides incisive commentary informed by three decades of living in and writing about his adoptive country.

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) last week offered us a glimpse of the violence it plans against Taiwan, with two days of blockade drills conducted around the nation and live-fire exercises not far away in the East China Sea. The PRC said it had practiced hitting “simulated targets of key ports and energy facilities.” Taiwan confirmed on Thursday that PRC Coast Guard ships were directed by the its Eastern Theater Command, meaning that they are assumed to be military assets in a confrontation. Because of this, the number of assets available to the PRC navy is far, far bigger

The 1990s were a turbulent time for the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) patronage factions. For a look at how they formed, check out the March 2 “Deep Dives.” In the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s the factions amassed fortunes from corruption, access to the levers of local government and prime access to property. They also moved into industries like construction and the gravel business, devastating river ecosystems while the governments they controlled looked the other way. By this period, the factions had largely carved out geographical feifdoms in the local jurisdictions the national KMT restrained them to. For example,

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of

Shunxian Temple (順賢宮) is luxurious. Massive, exquisitely ornamented, in pristine condition and yet varnished by the passing of time. General manager Huang Wen-jeng (黃文正) points to a ceiling in a little anteroom: a splendid painting of a tiger stares at us from above. Wherever you walk, his eyes seem riveted on you. “When you pray or when you tribute money, he is still there, looking at you,” he says. But the tiger isn’t threatening — indeed, it’s there to protect locals. Not that they may need it because Neimen District (內門) in Kaohsiung has a martial tradition dating back centuries. On