March 29 to April 4

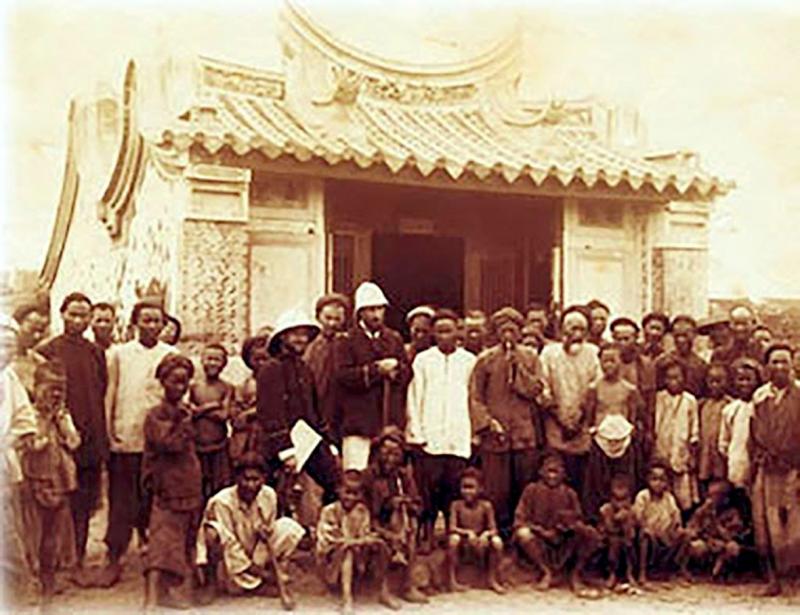

All Rene Coppin could see were burnt, collapsed and cannonfire-riddled houses when he landed in Magong (馬公, then spelled 媽宮), the main settlement of Penghu on April 24, 1885.

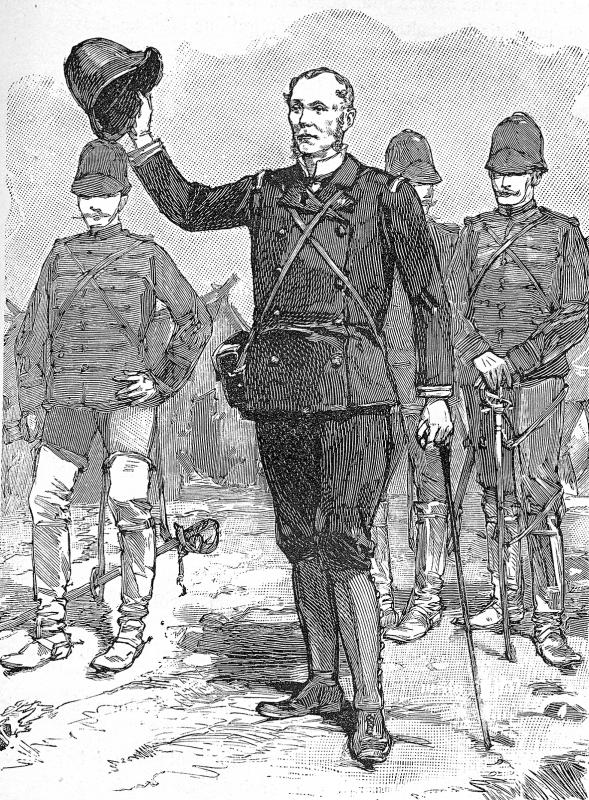

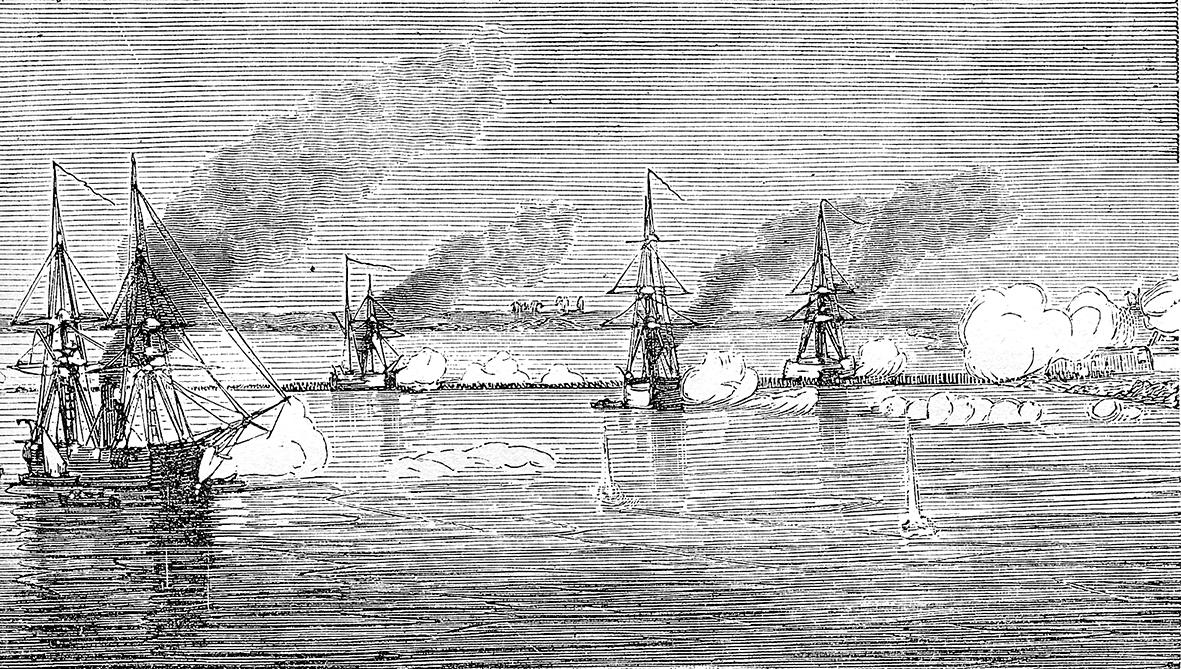

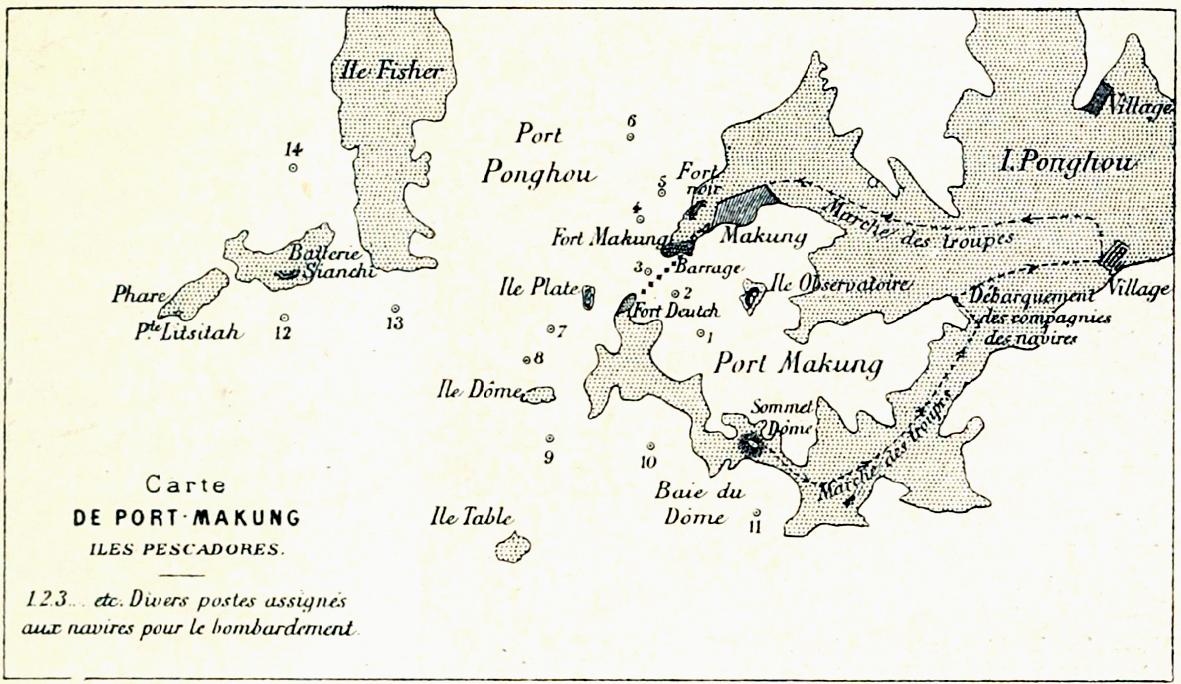

On March 29, French admiral Amedee Courbet led an invasion of the archipelago near the end of the Sino-French War, routing the Qing forces and capturing the town in three days. Coppin was a physician on the cruiser Nielly, and his letters to his mother, translated into Chinese in 2013 by Julie Couderc, provide first-hand information on the condition of Magong under its brief French occupation.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Scottish missionary William Campbell writes in Sketches from Formosa that shortly after the battle, “notifications were issued to inform all who were concerned that what was taking place arose from a quarrel between two nations.”

This would be the third time in history that Penghu got caught up in such a conflict. The Ming Dynasty engaged in a months-long struggle against the Dutch there in 1624, and the Qing Dynasty’s victory over the Tainan-based Kingdom of Tungning in 1683 paved the way for its annexation of Taiwan the following year.

After failing to capture Tamsui and Taipei despite taking Keelung in 1884, the French forces turned to Penghu to prevent the Qing from reinforcing its troops in Taiwan.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The victory probably didn’t affect the outcome of the war much — in fact, Courbet’s feat went largely unnoticed in France as the nation was more concerned about the collapse of then-prime minister Jules Ferry’s government. Peace talks began shortly after, and the French left Penghu in August.

TOWN IN RUINS

In addition to serving as a physician on the cruiser Nielly, Coppin served as assistant to the chief French physician on Courbet’s warship, the Bayard. He found Magong’s harbor to be beautiful, although the town lay in ruins. Much of it was damaged by French shelling, but the retreating Qing soldiers also engaged in looting and destruction.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

He praises Courbet’s campaign, noting that very few Qing soldiers got away. The Qing forts were toppled and all cannons destroyed, and its armory was flattened in an explosion that killed 600 troops.

“The fields have turned into graves, and with each step one could find artillery shells on the ground,” Coppin writes.

Coppin mentions the poor sanitary conditions, noting that Penghu was in the midst of a cholera outbreak and that countless French soldiers succumbed to the disease. Only those who mostly stayed on the Bayard avoided getting sick, although that wouldn’t be the case later.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The warship housed many Qing prisoners, who were brutally executed whenever they were caught trying to escape. Coppin witnessed one of these jailbreaks and participated in the operation to catch the escapees. The two survivors were tied to a stake on the beach and shot dead.

“This is my first time taking part in an execution, and I hope it’s my last,” he writes. “I didn’t have a choice as I was ordered to do so, but I could barely sleep the next evening. In my nightmare, I saw the two Qing escapees tied to the stakes. They were brave and their faces didn’t show any sign of fear.”

Despite violence against prisoners, Campbell writes that things were quite peaceful between the French and locals.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“The tumble-down condition of the buildings did not prevent hundreds of those who fled at the commencement of hostilities from returning, nor lessen their eager desire to earn as many as possible of those clean, Mexican dollars which now streamed in upon the place,” he writes.

The residents did all sorts of jobs for the French at reasonable prices, and spoke highly of Courbet when Campbell visited.

NO FINER COLONY

The book Le Mousse De L’amiral Courbet by a young sailor named Jean L. also details the French occupation of Penghu. According to the Academia Sinica-published Chinese version, the account is “neither historic nor fiction, but should be considered literary reportage.”

Jean L. also marveled at the beauty and scale of Magong’s harbor, and unlike Coppin he was overjoyed to stay in the town despite describing it as ugly and unsanitary. The locals were terrified of the French at first, but slowly relaxed their guard.

“They were no longer afraid of us, they resumed farming and flooded the streets and tried to rip us off whenever they could,” Jean L. writes. “But they’re not bad people, especially compared to those in [Keelung]!”

Apparently, merchants in Keelung gouged the French since they were in a more desperate situation trying to capture Taipei. In another sentence, however, Jean L. calls the people of Penghu “dirty and stupid.”

After almost losing his life to a water buffalo attack, Jean L. befriends a local fisherman, who teaches him about sharks and takes him fishing by moonlight. He tries shark fin, noting that it’s such a prized possession that locals are willing to sell their firstborn son’s inheritance for it. He also writes that the officers enjoyed collecting local arts and crafts, and was especially amused when a French pastor acquired a golden Buddha statue from a Penghu monk.

Jean L. was upset that the French decided to evacuate the archipelago, especially after they spent much effort fixing up the harbor, writing that his country possessed “no finer colony.”

After signing the peace accord, the French began moving their operations from Keelung to Penghu, and the port remained buzzing with foreign activity for the next few months. Courbet tried to persuade his government to keep the archipelago, to no avail.

As evacuation procedures continued, the admiral fell sick and died on June 11. On June 12, all the flags on the Bayard were lowered to half-mast, and Coppin helped preserve his corpse for the journey home. The ship departed Penghu on June 23 to a 19-gun salute, still bearing the scars of its fierce battles against the Qing.

Courbet’s belongings were buried in a gravesite in Magong alongside two French officers. The Japanese hired locals to watch over the site, but it was razed in 1953 to make way for the expansion of Magong High School. A small monument remains today.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Nine Taiwanese nervously stand on an observation platform at Tokyo’s Haneda International Airport. It’s 9:20am on March 27, 1968, and they are awaiting the arrival of Liu Wen-ching (柳文卿), who is about to be deported back to Taiwan where he faces possible execution for his independence activities. As he is removed from a minibus, a tenth activist, Dai Tian-chao (戴天昭), jumps out of his hiding place and attacks the immigration officials — the nine other activists in tow — while urging Liu to make a run for it. But he’s pinned to the ground. Amid the commotion, Liu tries to

A dozen excited 10-year-olds are bouncing in their chairs. The small classroom’s walls are lined with racks of wetsuits and water equipment, and decorated with posters of turtles. But the students’ eyes are trained on their teacher, Tseng Ching-ming, describing the currents and sea conditions at nearby Banana Bay, where they’ll soon be going. “Today you have one mission: to take off your equipment and float in the water,” he says. Some of the kids grin, nervously. They don’t know it, but the students from Kenting-Eluan elementary school on Taiwan’s southernmost point, are rare among their peers and predecessors. Despite most of

A pig’s head sits atop a shelf, tufts of blonde hair sprouting from its taut scalp. Opposite, its chalky, wrinkled heart glows red in a bubbling vat of liquid, locks of thick dark hair and teeth scattered below. A giant screen shows the pig draped in a hospital gown. Is it dead? A surgeon inserts human teeth implants, then hair implants — beautifying the horrifyingly human-like animal. Chang Chen-shen (張辰申) calls Incarnation Project: Deviation Lovers “a satirical self-criticism, a critique on the fact that throughout our lives we’ve been instilled with ideas and things that don’t belong to us.” Chang

Feb. 10 to Feb. 16 More than three decades after penning the iconic High Green Mountains (高山青), a frail Teng Yu-ping (鄧禹平) finally visited the verdant peaks and blue streams of Alishan described in the lyrics. Often mistaken as an indigenous folk song, it was actually created in 1949 by Chinese filmmakers while shooting a scene for the movie Happenings in Alishan (阿里山風雲) in Taipei’s Beitou District (北投), recounts director Chang Ying (張英) in the 1999 book, Chang Ying’s Contributions to Taiwanese Cinema and Theater (打鑼三響包得行: 張英對台灣影劇的貢獻). The team was meant to return to China after filming, but