We’ve wrapped up our interview and are walking to get coffee when Mucahid Bayrak points to a People’s Republic of China flag. It hangs from an apartment balcony near National Taiwan Normal University (NTNU), where Bayrak is an assistant professor in the Department of Geography.

“In Taiwan, you can do something like that, unlike in much of Asia,” he says, underscoring a point he’d made during our conversation.

I reached out to Bayrak late last year, after coming across a paper he’d recently lead-authored, titled “The effect of cultural practices and perceptions on global climate change response among Indigenous peoples: a case study on the [At]ayal people in northern Taiwan” and published in Environmental Research Letters.

Photo courtesy of Mucahid Bayrak

The Atayal (泰雅) are one of 16 Aboriginal communities recognized by the government. Aboriginal people account for 2.4 percent of the country’s population.

The first sentence of the paper, which Bayrak wrote with two NTNU colleagues, acknowledges that Aboriginal peoples “are disproportionately affected by climate change.”

Given his non-Han name, I wondered if Bayrak was himself Aboriginal. He isn’t, it turns out.

Photo courtesy of Mucahid Bayrak

A Dutchman with Turkish ancestry, Bayrak did research among Vietnam’s indigenous people (the so-called Montagnards) for his PhD studies at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He describes himself as “passionate about forest dependent communities, conservation initiatives and sustainable livelihood development.”

Bayrak, who joined NTNU’s faculty in 2018, has conducted extensive surveys and interviews among Atayal residents (and some of their Han-Taiwanese neighbors) in Taoyuan’s Fusing District (復興) and Yilan County’s Nanao Township (南澳) to understand their attitudes towards climate change.

“Cultural dimensions and perceptions certainly matter,” he says. “If you talk to indigenous people — and not only in Taiwan — there’s a divide between the climate-change discourses they get from the media or their government, and their own observations,” he says.

Photo courtesy of Mucahid Bayrak

Bayrak says one reason why there isn’t always a strong link between what Aboriginal people report seeing with their own eyes and the picture of global climate change they get from TV or the Internet is that local observations often go beyond the lifetime of the interviewee.

He’s noticed that, when discussing current conditions, it isn’t uncommon for Aboriginal people to reference what happened in their parents’ or grandparents’ time.

“Indigenous knowledge is often communicated through songs, stories and rituals,” says Bayrak. “Compared to science, the way in which cultures generate, disseminate and perceive knowledge is broader.”

TRADITION VS MODERNITY

It’s important to recognize the contrast between traditional Aboriginal beliefs and what’s variously called modern, industrialized or Western thinking, he argues.

The latter, influenced by Western ontologies of nature, “includes elements of ‘God created this world for you, so go ahead and take what’s yours,’ whereas non-monotheistic or indigenous worldviews often teach: ‘You’re not the center of the world, you’re part of it. If you take care of this environment, it’ll take care of you,’” he says.

To stress the relationship Taiwan’s Aboriginal people have traditionally had with their land, some Aboriginal scholars have imported the Australian Aboriginal concept of “country.” This doesn’t refer to the modern state, but rather the terrain, the living things and spirits which inhabit it, its as well as its myths and seasons.

Bayrak describes this as “a very valuable idea.”

“When you can understand what environmental change means for people’s worldviews, you put indigenous people on a more equal footing, because you’re not taking ‘Western’ science as your point of departure, but rather indigenous knowledge is your point of departure,” he says.

“We should treasure these different forms of knowledge. They might conflict at times, but we should acknowledge that there are multiple ways of looking at the environment. At the same time, saying ‘indigenous people are at one with nature’ is too simplistic.”

Bayrak stresses that many indigenous communities have great flexibility when it comes to dealing with change. Many Atayal perceive dramatic climate-related events not necessarily as disasters, but rather as natural — and sometimes even desirable — phenomena, he says.

The “Cultural practices and perceptions” paper quotes an Atayal farmer as asserting that if typhoons don’t strike the mountains, the problem of bees attacking people becomes more serious.

When Aboriginal peoples engage in commercial agriculture, they lose some of their flexibility.

“I’ve seen that with indigenous farmers growing rubber or coffee in Vietnam, and with fruit farmers in Fusing,” says Bayrak.

As the paper points out, Fusing’s peach farmers lost almost their entire 2019 harvest because of unseasonably warm conditions that February. One interviewee told to researchers that the weather “is becoming more unpredictable each year.”

Bayrak says that when Aboriginal communities are given the right to control their hunting grounds or waterways, they’re often very effective at managing them sustainably.

Danaiku (達娜伊谷) near Alishan (阿里山), where the community has worked together to protect river resources and establish an ecotourism park, is an excellent example, he says.

However, successes like Danaiku or Smangus (司馬庫斯) in Hsinchu County can limit the space for experimentation elsewhere.

“Those two places are often held up as model villages. Other indigenous villages are expected to behave just like them, and replicate the model,” Bayrak says.

If Bayrak is more optimistic than some observers about the future of Taiwan’s Aboriginal minority, in part it’s because of the country’s political plurality.

Several of the resettlement communities where Aboriginal people were encouraged to relocate following 2009’s Typhoon Morakot remind Bayrak of the fake made-for-TV town in the movie The Truman Show.

“But at least they triggered a debate about the cultural aspects of disaster recovery and reconstruction. In some parts of the Asia Pacific, there’s no way a discussion like this could happen. They’d resettle you — and, if you’re critical, they’d lock you up,” he says.

“In liberal democracies, there’s more discussion about indigenous people’s rights, and trying to undo historical injustices. In the Asia-Pacific, Taiwan has been at the forefront of this discussion, on a par with New Zealand,” he says, asking: “Just as marriage equality and the government’s response to COVID-19 have enhanced Taiwan’s reputation, is there a way we can put Taiwan on the global map for indigenous peoples’ rights?”

Steven Crook, the author or co-author of four books about Taiwan, has been following environmental issues since he arrived in the country in 1991. He drives a hybrid and carries his own chopsticks.

In 2020, a labor attache from the Philippines in Taipei sent a letter to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs demanding that a Filipina worker accused of “cyber-libel” against then-president Rodrigo Duterte be deported. A press release from the Philippines office from the attache accused the woman of “using several social media accounts” to “discredit and malign the President and destabilize the government.” The attache also claimed that the woman had broken Taiwan’s laws. The government responded that she had broken no laws, and that all foreign workers were treated the same as Taiwan citizens and that “their rights are protected,

A white horse stark against a black beach. A family pushes a car through floodwaters in Chiayi County. People play on a beach in Pingtung County, as a nuclear power plant looms in the background. These are just some of the powerful images on display as part of Shen Chao-liang’s (沈昭良) Drifting (Overture) exhibition, currently on display at AKI Gallery in Taipei. For the first time in Shen’s decorated career, his photography seeks to speak to broader, multi-layered issues within the fabric of Taiwanese society. The photographs look towards history, national identity, ecological changes and more to create a collection of images

The recent decline in average room rates is undoubtedly bad news for Taiwan’s hoteliers and homestay operators, but this downturn shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone. According to statistics published by the Tourism Administration (TA) on March 3, the average cost of a one-night stay in a hotel last year was NT$2,960, down 1.17 percent compared to 2023. (At more than three quarters of Taiwan’s hotels, the average room rate is even lower, because high-end properties charging NT$10,000-plus skew the data.) Homestay guests paid an average of NT$2,405, a 4.15-percent drop year on year. The countrywide hotel occupancy rate fell from

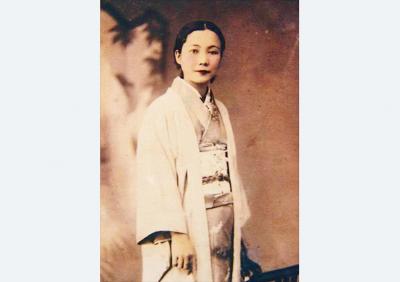

March 16 to March 22 In just a year, Liu Ching-hsiang (劉清香) went from Taiwanese opera performer to arguably Taiwan’s first pop superstar, pumping out hits that captivated the Japanese colony under the moniker Chun-chun (純純). Last week’s Taiwan in Time explored how the Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) theme song for the Chinese silent movie The Peach Girl (桃花泣血記) unexpectedly became the first smash hit after the film’s Taipei premiere in March 1932, in part due to aggressive promotion on the streets. Seeing an opportunity, Columbia Records’ (affiliated with the US entity) Taiwan director Shojiro Kashino asked Liu, who had