March 22 to March 28

George Wang (王玨) was bewildered when he was asked to play the role of Machete, a Mexican villain in the 1967 Italian spaghetti Western, Taste of Killing. The tall, dark-skinned Wang had portrayed Taiwanese Aborigines, Mongolians, Japanese and Koreans, but this would be his first non-Asian role.

He recalls in his memoir that the film studio agent showed him pictures of various Mexicans and said, “They look more Chinese than you do.”

Photo: Chen Yi-chuan, Taipei Times

They shoved Wang into the audition room, where director Tonino Valerii was more than pleased with his performance. Wang recalls spending the afternoon watching two Mexican films to prepare, and then winging it.

Wang says that he made history as the first Asian actor to play a non-Asian role in a non-Asian country.

“Toshiro Mifune participated in foreign productions, but he always portrayed Japanese characters. Bruce Lee (李小龍) and Jackie Chan (成龍) also appeared in foreign productions, but they never portrayed foreigners. As for me, I’ve portrayed Mexcians, Arabs … I’ve also played a Confederate general in a Civil War film, and a chief from northern Africa.”

Photo: Chen Yi-chuan, Taipei Times

Wang, who led a daring mission in 1949 to transport all of China Motion Picture Studio’s (中國電影製作公司) equipment to Taiwan right before Shanghai fell to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), became one of Taiwan’s top actors before making it big in Italy. He starred in more than 50 Italian productions before returning to Taiwan in 1978.

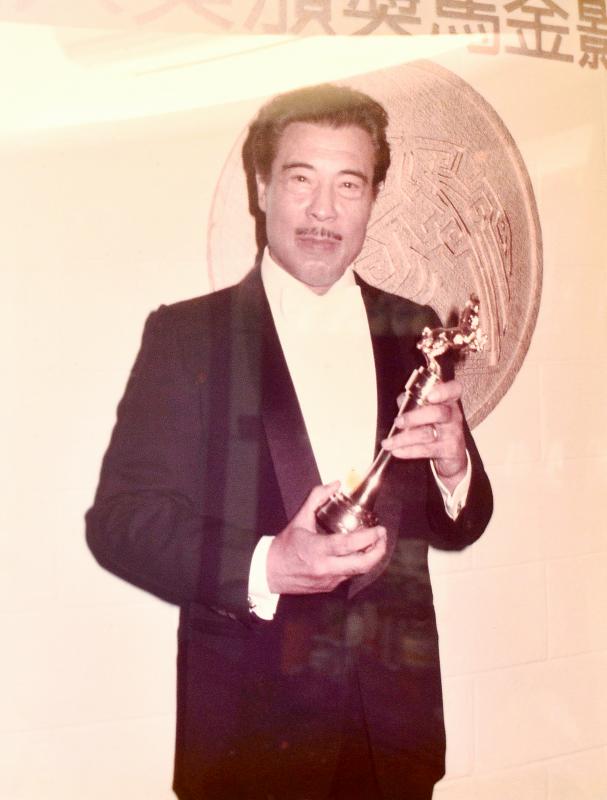

He won a Golden Horse for best supporting actor in the 1980 film The Coldest Winter in Peking (皇天后土), and was given the Special Contribution Award in 2009. At the age of 95, Wang appeared in his final production, Hong Kong director Wong Kar-wai’s (王家衛) The Grandmaster (一代宗師). He died on March 27, 2015.

WARTIME THESPIAN

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Born in 1918 in today’s Liaoning Province, Wang joined the resistance against the Japanese invasion of China as a young man. He had hoped to see combat, but in 1938 the studio recruited him to act in propaganda films. Wang starred in seven patriotic, anti-Japanese productions over the course of the war and also participated in a number of plays.

He came to Taiwan for the first time in July 1947 to shoot Hualien Port (花蓮港), which was helmed by Taiwanese director Ho Fei-kuang (何非光). Ho moved to China in 1930 and joined the studio after studying filmmaking in Japan. He later enlisted in the PLA and remained in China for the rest of his life.

Hualien Port was billed as the “first nationalistic blockbuster featuring Taiwan’s [Aborigines]” and stressed that it included over 800 Aboriginal actors. However, the main cast was almost entirely Chinese. This was just months after the 228 Incident, an anti-government uprising that was violently suppressed by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), and the movie tried to deliver a message of ethnic harmony and “build Taiwan together.”

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Film Institute

Wang seems to have spoken to locals at length about the 228 Incident while in Taiwan and understood the causes. He also took the opportunity to collect material on the Wushe Incident (霧社事件), an 1930 anti-Japanese uprising by the Aboriginal Seediq people, for a future project that never came to fruition.

By early 1949, it was clear that the KMT was about to lose the Chinese Civil War. The Shanghai studio’s top brass had all fled, and Wang was left in charge. He noted during his time in Taiwan the lack of local filmmaking resources, and decided to move all of the studio’s equipment across the Taiwan Strait. With the communists closing in, Wang’s team spent two days packing everything up into 12 trucks — only to be told at the port’s gate that the ships were full.

The slick-talking, well-connected Wang convinced the port’s commander (who was of the same military rank) into letting two of the trucks on, but once the gate opened, all 12 vehicles forced their way through.

According Wang’s memoir, the commander yelled: “Colonel Wang, you didn’t keep your word!” Wang hid in the first truck and kept silent, thinking, “This is wartime and I’m trying to protect national property. I don’t care if I keep my word or not.”

In May 1949, the equipment, along with the film crew, safely arrived in Keelung. The communists overran Shanghai by the end of the month.

HEADING WEST

Wang got to work immediately, staging a well-received, four-hour-long play at Zhongshan Hall about the anti-Japanese effort in the Golden Triangle just three months after arrival. The movie studio resumed production the following year.

Their second film, Never Seperate (永不分離), which was shot in Yilan, was shown in Australia, where the local press dubbed Wang the “Clark Gable of the East.”

In 1959, Italian actor and director Renzo Merusi arrived in Taiwan after being denied entry to China. Merusi had been unsuccessfully looking for two months for someone to play the Chinese Communist villain in The Dam on the Yellow River, and he knew he had his man when he saw Wang.

Merusi flew Wang to Italy to complete the project, and persuaded him to pursue his career there. Wang ended up spending nearly two decades in Italy, where he portrayed all sorts of characters of various ethnicities and won a national acting award in 1975. He recalls portraying a Mexican character in at least 10 spaghetti Western productions.

In 1973, Wang facilitated a collaboration with Hong Kong’s legendary Shaw Brothers studio, This Time I’ll Make You Rich. His one stipulation was that it be partially shot in Taiwan; he had been away for so long and he wanted to see his old friends and colleagues.

Wang opened his own studio in Hong Kong a few years later, and eventually resettled in Taipei. He stayed busy for the next three decades, appearing in numerous films, plays and television dramas. His second son Wang Tao (王道) also became an actor, starring in numerous kung fu flicks in the late 70s and early 80s.

Now 72, the younger Wang remains active in local television productions, most recently appearing in last year’s Here Comes Fortune Star (廢財闖天關) by Sanlih E-Television (三立).

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.