March 01 to March 07

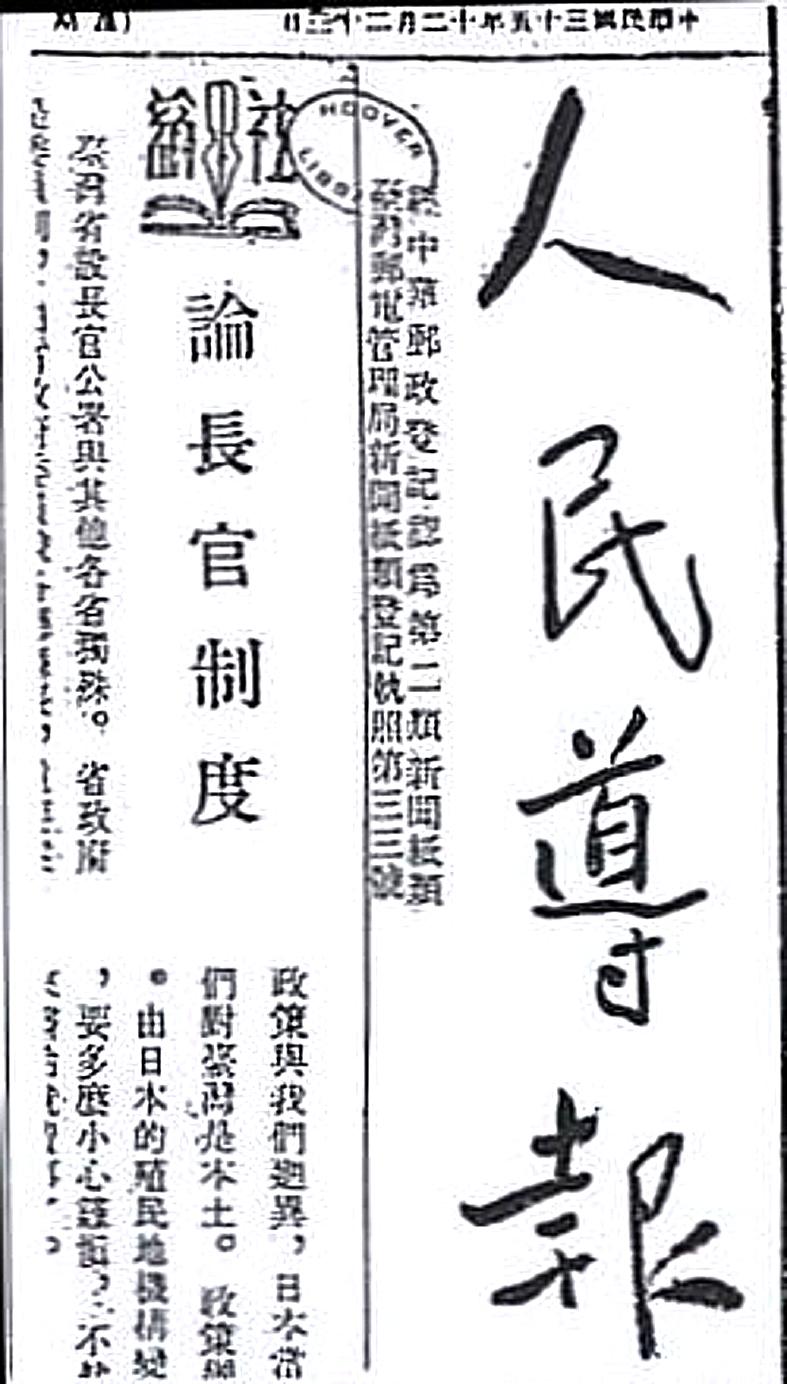

There was only one Taiwanese department head in Taiwan’s first post-World War II provincial government: Sung Fei-ju (宋斐如), who served as deputy director of the department of education. Sung, who lived in China for over two decades, had close ties with the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and was also allowed to start his own newspaper, the People’s News-Leader (人民導報).

Aside from Sung, only a handful of Taiwanese held significant positions in the government, almost all of them banshan (半山, half mountain) like him. The term refers to those who moved to China and returned to Taiwan after World War II.

.jpg)

Photo courtesy of Lin Hsiao-feng

Sung’s standing, however, did not save his neck during the 228 Incident, an anti-government uprising on Feb. 28 1947 that was brutally suppressed. He was dragged away from his home on March 11 and never seen again.

Lin Cheng-te’s (林政德) book Banshan and 228 (半山與二二八) explores the various roles these banshan took up before, during and after the incident. Despite their allegiance to the government, they tried to help their people in their own way, and in Sung’s case, paid the ultimate price for it.

HOPEFUL RETURN

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

As World War II neared its end, the KMT set up a committee led by future governor-general Chen Yi (陳儀) to make plans for the takeover and rule of Taiwan. Several founding members were banshan, and Sung joined the following year. They flew to Taipei on Oct. 5, 1945, set up headquarters and began working with local elites such as Lin Hsien-tang (林獻堂) to prepare for the Japanese governor-general’s formal surrender on Oct. 25.

Sung was one of many Taiwanese who, unsatisfied with Japanese rule, turned to the “motherland” of China. He moved to Beijing in 1922 to attend university, and from 1932 to 1935 served as adviser and tutor to the powerful warlord Feng Yuxiang (馮玉祥) and his family. Sung penned numerous papers and launched a publication to help the government better understand and resist Japanese aggression, and was recognized for his efforts.

Sung was in favor of the KMT taking over Taiwan from Japan, and was initially confident that this would liberate Taiwanese from the shackles of colonial oppression. With fellow banshan Lee You-pang (李友邦), Sung formed the Taiwan Revolution Alliance (台灣革命聯盟) in 1941 to promote the idea among Taiwanese in China, many of whom felt discriminated against since they were often treated as Japanese. Until the end of the war, Sung devoted his time to training personnel to help rebuild and govern Taiwan.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Sung continued his mission of education in his new position upon arriving in Taiwan, and his People’s News-Leader aimed to “dispel past misbeliefs, promote the culture of the motherland, communicate both national and international current events and ideas, promulgate government’s policies, report on social issues and help build a new Taiwan based on the Three Principles of the People.”

Disillusion toward the KMT came quickly, and soon the paper was frequently criticizing Chen Yi’s policies and also reporting on sensitive topics regarding the Chinese Civil War. An irate Chen forced Sung to either quit his government job or step down from the paper. Sung chose the latter, but was reinstated a few months later. Nine days before the 228 Incident broke out, Sung was removed from his post on the grounds that public servants could not run a newspaper.

Sung’s colleagues advised him to flee to Hong Kong after the uprising started, but he stayed to help the paper report on the events. On March 8, the authorities shut down the paper.

Sung did not participate in the incident in any other way, so why was he executed? Due to his relentless criticism of the government and some of the paper’s past rhetoric (such as using “communist army” instead of “communist bandits”), secret agents framed Sung as the “Communist Party leader of Taiwan,” which amounted to a death sentence.

The tragedy doesn’t end there. Sung’s wife, Chu Yen-hua (區嚴華), was arrested in September for harboring a wanted couple and helping them escape Taiwan. She was executed in January 1950.

TRAGIC COUPLE

Lee You-pang also hated the Japanese. He fled Taiwan after launching several student attacks on Japanese police stations and continued his anti-Japanese crusade in China after graduating from the Whampoa Military Academy.

He returned home in December 1945 and was appointed as leader of the Taiwan branch of the Three Principles Youth Group (三民主義青年團). But despite his contributions to the war, Chen Yi suddenly disbanded his Taiwan Militia (台灣義勇隊) without discharge orders or pension.

Perhaps Lee was too naive. He once openly stated that he hoped to recruit as many members into the Youth Group to “reform” the KMT, which he thought was too corrupt. This obviously did not sit well with the top brass.

When the 228 Incident broke out, Chen Yi asked Lee to broadcast a plea for the people to stop fighting, but Lee refused and criticized Chen: “I’ve been telling you this whole time to quit being corrupt and rule fairly, as that is the only way to win the support and hearts of the people. You didn’t listen, and now everything has spiraled out of control. How can I stop this chaos by just uttering a few sentences?”

BESEECHING CHIANG CHING-KUO

Lee was arrested on March 10, a day before Sung disappeared. He was taken to Nanjing, where the Three Principles Youth Group was headquartered. Lee’s wife, Yen Hsiu-feng (嚴秀峰), traveled to Nanjing and after a month had an audience with Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國), the son of KMT leader Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) and an officer in the Youth Group’s central command.

Chiang told her Lee was charged with inciting Taiwan’s Youth Group members to riot and harboring communists. Yen pleaded her case, and a subsequent government investigation showed her versions of the events to be true. Lee was released a few months later, narrowly escaping death.

Lin writes that this showed that despite just holding a minor position, Chiang already wielded considerable influence, and also that he was less stubborn than his father.

However, trouble didn’t end for the family there. In February 1950, Yen was sentenced to 15 years in prison for failing to report a communist, while Lee was arrested the following year and charged with harboring communists and attempting to overthrow the government. He was executed on April 22, 1952.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Most heroes are remembered for the battles they fought. Taiwan’s Black Bat Squadron is remembered for flying into Chinese airspace 838 times between 1953 and 1967, and for the 148 men whose sacrifice bought the intelligence that kept Taiwan secure. Two-thirds of the squadron died carrying out missions most people wouldn’t learn about for another 40 years. The squadron lost 15 aircraft and 148 crew members over those 14 years, making it the deadliest unit in Taiwan’s military history by casualty rate. They flew at night, often at low altitudes, straight into some of the most heavily defended airspace in Asia.

Beijing’s ironic, abusive tantrums aimed at Japan since Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi publicly stated that a Taiwan contingency would be an existential crisis for Japan, have revealed for all the world to see that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) lusts after Okinawa. We all owe Takaichi a debt of thanks for getting the PRC to make that public. The PRC and its netizens, taking their cue from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), are presenting Okinawa by mirroring the claims about Taiwan. Official PRC propaganda organs began to wax lyrical about Okinawa’s “unsettled status” beginning last month. A Global

Taiwan’s democracy is at risk. Be very alarmed. This is not a drill. The current constitutional crisis progressed slowly, then suddenly. Political tensions, partisan hostility and emotions are all running high right when cool heads and calm negotiation are most needed. Oxford defines brinkmanship as: “The art or practice of pursuing a dangerous policy to the limits of safety before stopping, especially in politics.” It says the term comes from a quote from a 1956 Cold War interview with then-American Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, when he said: ‘The ability to get to the verge without getting into the war is

Like much in the world today, theater has experienced major disruptions over the six years since COVID-19. The pandemic, the war in Ukraine and social media have created a new normal of geopolitical and information uncertainty, and the performing arts are not immune to these effects. “Ten years ago people wanted to come to the theater to engage with important issues, but now the Internet allows them to engage with those issues powerfully and immediately,” said Faith Tan, programming director of the Esplanade in Singapore, speaking last week in Japan. “One reaction to unpredictability has been a renewed emphasis on