Taiwan’s oldest surviving Christian house of worship stands in a village at the base of the Central Mountain Range. Upgraded to a basilica minore by Pope John Paul II in 1984, Wanjin Basilica (萬金聖母聖殿) was established in what’s now Pingtung County’s Wanluan Township (萬巒) in 1863.

The church’s founder, Dominican priest Father Fernando Sainz (郭德剛), was one of the first missionaries to enter Taiwan after the signing in mid-1858 of treaties between Qing China (which ruled the island between 1684 and 1895), France, Great Britain, Russia and the US.

These agreements, collectively known as the Treaty of Tianjin (天津條約), compelled the Qing Dynasty to lift all restrictions on the practice of Catholic, Protestant and Orthodox Christianity. However, it seems this clause wasn’t clearly communicated to every level of the Qing bureaucracy. After Sainz, his fellow Dominican preacher Father Angel Bofurull and four Chinese converts arrived at Takow (today’s Kaohsiung) from the Philippines on May 15, 1859, they were detained by the local magistrate for two days.

Photo: Steven Crook

Once they were freed, things didn’t get much easier. Before the end of the year, illness forced Bofurull to quit the mission, and it’s not clear if the Chinese converts stayed on. At one point Sainz was alone, homeless and having to sleep on a beach.

The Spaniard persisted, and with the help of Matthew Rooney — a Takow-based Irish-American who traded in camphor and opium — he eventually found a place to stay.

Sainz established a church in 1861 in what’s now downtown Kaohsiung. That chapel is long gone, and it’s for his church-planting efforts in the interior that the priest is best remembered.

Photo: Steven Crook

Ordered to search for descendants of Aboriginal people who’d become Christians in the 17th century, when the Protestant Dutch dominated south Taiwan, Sainz ventured across the lowlands where Han settlers were continuing to push the indigenous inhabitants into hillier territory.

Just over 30km due east of his first church, he found a Makatao (馬卡道) community that proved receptive to his message. The Makatao of Wanjin saw Sainz not only as a religious instructor, but also as an outsider whose connection to the Western powers then penetrating East Asia could protect them from the Han majority.

Whether Sainz’s presence helped the Makatao, or actually attracted greater aggression, is moot. The Roman Catholic outpost in Wanjin was the target of repeated attacks by Hakka militia and Paiwan Aboriginal warriors. Sainz himself was kidnapped by Hakka settlers in late 1867, and only released after a ransom of 50 silver dollars was paid. (This was a substantial amount of money; buying the largish plot on which the church stands had cost the priest 62 silver dollars.)

Photo: Steven Crook

The first building, made of adobe and wood, was flattened by an earthquake. Father Francisco Herce (良方濟), who took over as Wanjin’s full-time priest in 1869, oversaw the construction of a larger and more durable “Spanish fortress-style” edifice. If you’ve been to the Philippines, this type of architecture will look familiar.

The basilica is 35m long, 13.7m wide and 7.6m tall. The walls, which in places are 1.3m thick, are made of bricks and stones cemented with a blend of gravel, lime, brown sugar, honey and kapok fiber. Much of the skilled construction work was done by masons and carpenters brought in from Fujian Province, China. Local churchgoers contributed unpaid labor.

The belfry was originally in the center. After it fell down in the 1940s, it was rebuilt on the southern side of the building (on the right as you face the front of the church). The bell was cast in Spain.

Photo: Steven Crook

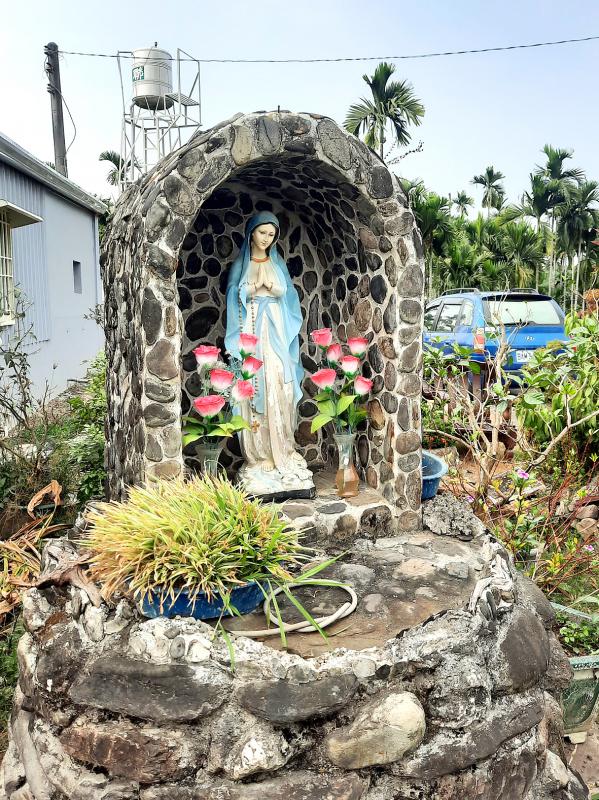

The church continues to play a central role in the life of the village. It’s said that four fifths of Wanjin’s 2,000-plus people are Catholic — a remarkable proportion, given that Catholics are barely one percent of Taiwan’s population. Marian shrines can be found throughout the village.

Every year, on both the Feast of the Immaculate Conception (December 8) and on Christmas Day, thousands of Catholics from other parts of the country converge on Wanjin Basilica.

At other times, the church draws a steady stream of secular tourists. Those who know what to look for scan the facade for an A4-sized slab of granite near the roof, directly below the cross.

Photo: Steven Crook

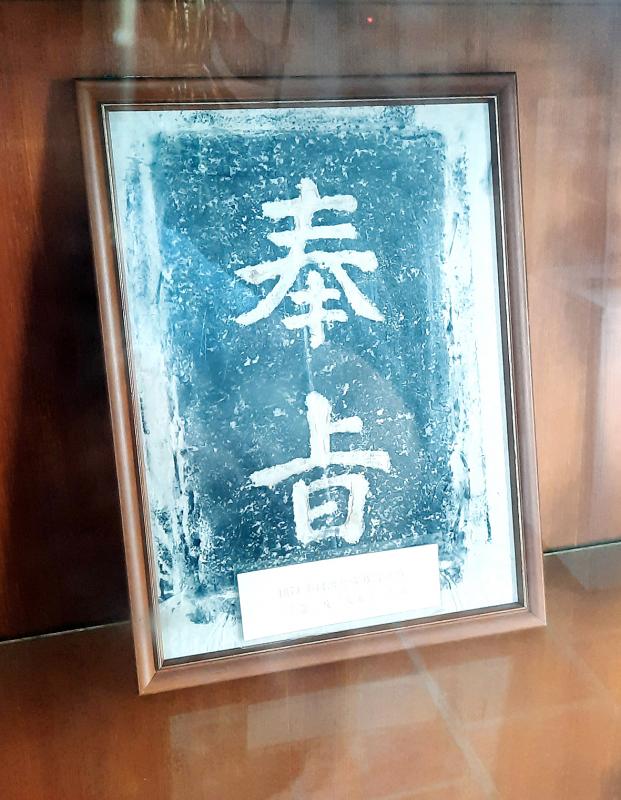

Inscribed with the Chinese characters fengzhi (奉旨, “decreed by the highest authorities”), this stone was issued to the church in 1874 on the orders of Emperor Tongzhi (同治), to show that the mission enjoyed imperial protection. It may have had some effect, as the overt hostility previously shown by neighboring settlements quickly subsided.

The church is very visitor-friendly in the sense its doors and grounds are open to the public all day and every day. However, of the items preserved inside display cabinets, none are labeled in English, and very little Chinese-language information is provided. For Taiwanese who grew up unexposed to Catholicism, these exhibits will likely mean nothing.

In addition to priests’ vestments, there is a chalice, a thurible (a small censer suspended by chains), an oil stock (a vessel for holy anointing oil) and a charcoal rubbing of the 1874 edict.

Non-religious mementos include: an Aboriginal headdress decorated with feathers and white lilies; a blow pipe and darts; a hunting rifle; two old cameras; a pair of spectacles; a pair of binoculars; a saxophone; and antique timepieces.

The interior of the basilica is, by Catholic standards, quite plain. Yet there’s definitely something beguiling about Wanjin, its church, the mission’s history and the mountains which — if you’re blessed with good weather — form a gorgeous backdrop.

Steven Crook has been writing about travel, culture and business in Taiwan since 1996. He is the author of Taiwan: The Bradt Travel Guide and co-author of A Culinary History of Taipei: Beyond Pork and Ponlai.

Most heroes are remembered for the battles they fought. Taiwan’s Black Bat Squadron is remembered for flying into Chinese airspace 838 times between 1953 and 1967, and for the 148 men whose sacrifice bought the intelligence that kept Taiwan secure. Two-thirds of the squadron died carrying out missions most people wouldn’t learn about for another 40 years. The squadron lost 15 aircraft and 148 crew members over those 14 years, making it the deadliest unit in Taiwan’s military history by casualty rate. They flew at night, often at low altitudes, straight into some of the most heavily defended airspace in Asia.

Beijing’s ironic, abusive tantrums aimed at Japan since Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi publicly stated that a Taiwan contingency would be an existential crisis for Japan, have revealed for all the world to see that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) lusts after Okinawa. We all owe Takaichi a debt of thanks for getting the PRC to make that public. The PRC and its netizens, taking their cue from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), are presenting Okinawa by mirroring the claims about Taiwan. Official PRC propaganda organs began to wax lyrical about Okinawa’s “unsettled status” beginning last month. A Global

Taiwan’s democracy is at risk. Be very alarmed. This is not a drill. The current constitutional crisis progressed slowly, then suddenly. Political tensions, partisan hostility and emotions are all running high right when cool heads and calm negotiation are most needed. Oxford defines brinkmanship as: “The art or practice of pursuing a dangerous policy to the limits of safety before stopping, especially in politics.” It says the term comes from a quote from a 1956 Cold War interview with then-American Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, when he said: ‘The ability to get to the verge without getting into the war is

Dec. 22 to Dec. 28 About 200 years ago, a Taoist statue drifted down the Guizikeng River (貴子坑) and was retrieved by a resident of the Indigenous settlement of Kipatauw. Decades later, in the late 1800s, it’s said that a descendant of the original caretaker suddenly entered into a trance and identified the statue as a Wangye (Royal Lord) deity surnamed Chi (池府王爺). Lord Chi is widely revered across Taiwan for his healing powers, and following this revelation, some members of the Pan (潘) family began worshipping the deity. The century that followed was marked by repeated forced displacement and marginalization of