Whether or not the Formosan clouded leopard still exists in some hidden mountain fastness somewhere in Taiwan is a question that has fascinated the scientific community for many years. Taiwanese researchers attempted to put the question to rest a decade ago by scouring the Dawushan Nature Reserve (大武山) in Taitung County, but came back empty-handed.

The survey ran from 1997-2012 and used over a thousand camera traps, but did not turn up a single cat, and the species was declared extinct in 2013. Renowned Taiwanese conservationists Chiang Po-jen (姜博仁) and Kurtis Pei (裴家騏) conducted the field work and published a definitive paper on the failed hunt.

In short, clouded leopards were not found, but prey species abound and, surprisingly, many Taiwanese are supportive of reintroduction. Yet it may still lurk out there, just not where scientists think, and finding it might require a different approach.

Photo courtesy of the National Taiwan Museum

SEARCHING FOR A LEOPARD

Chiang and his team used standard and rigorous scientific methodology, laying out their camera stations in a grid style, which is widely used in conservation today. However, finding a rare and cryptic species might be more of an art than a science.

Chiang, Pei and their colleagues are — unlike myself — trained scientists. Nonetheless, I’ve organized and led wildlife camera trap surveys in Cambodia, Thailand and Indonesia, and we found clouded leopards in all of our study sites, one of which (in Sumatra) is not even a protected area but a leftover land of isolated mountains and gorges.

Photo courtesy of Taipei Zoo

In the challenging terrain of Southeast Asia, and with a very limited number of camera traps, intuition trumped science when choosing camera stations. A study of maps and reconnaissance trips into the deep interior to get a feeling for the place was our basic approach.

We went in search of haunted headwaters where access was difficult and where trails were few, and where animist beliefs trumped Islamic faith. We would explore, and get a feeling. Could tigers roam here? How about clouded leopards? Some places felt magical, and that’s where cameras went.

The surveys turned up: Sumatran tiger and Sunda clouded leopard (in Sumatra); we rediscovered Asian elephants in Virachey National Park in Cambodia in an area that one ranger insisted was a waste of time, and those cameras recorded clouded leopard too; finally, clouded leopards were on most of our camera traps in Thailand.

Photo: Gregory McCann

Taiwan’s Jhiben Gorge (知本) is so vast and so untouched by humans that it is at least possible to imagine that a small population of Formosan clouded leopards persists. This area is upriver from the hot springs, a place the late Lonely Planet Taiwan author Robert Story described as “the closest to Nirvana as you’re likely to get.”

Another Taiwanese conservationist said over coffee a few months back that the Jhiben Gorge of Taitung hadn’t been surveyed in 25 years. Pei told me a few years back that the Jhiben River was the last place otters were found on Taiwan.

And so I headed to Jhiben last month. I hadn’t visited since January 2009, and I heard from multiple sources that Typhoon Morakot of August later that year obliterated sections of the canyon, collapsing entire mountains, as well as hotels. I didn’t know what to expect.

A TUMBLE DOWN

An old friend who I had brought down to Jhiben back in 2003 was already there ahead of me and was in the midst of a 5-day solo river-trace up the canyon. I hoped to find him while conducting day hikes.

I spent the first day getting as far up the river as I could, keeping an eye out for possible camera stations. I only had two camera traps on me and I would only be setting them up for a couple of days as I didn’t have permission. I espied many enticing locales.

The gorge is now much more walkable than it used to be, with narrow sections of warped rock canyon having been blown out by Morakot and turned to rocky beaches. Pausing to look at what appeared to me to be a small game trail near the top of a bulge of rock at the base of a cliff, I took off my bag and clambered up the slippery surface, sliding down more than once, but finally reaching the root of a tree I had in mind as a camera anchor.

Images of pangolin, Siberian weasel, masked palm civet and clouded leopard flashed through my mind. It was not easy to get the camera properly angled down, so I began reaching for sticks to jam behind it, lost my balance and tumbled 20 feet down.

At the bottom, I rolled through underbrush and came upon a serow skull. I eventually got the cam set and later came upon another spot that caught my eye, so I climbed up there and deployed. (In two days, I got a mere three “ghost shots.”)

KEEP ON LOOKING

Cams set, I continued, finding new paradise waterfalls I had never seen before, as well as countless crystal blue pools. At 4pm I stopped, and wrote my name in the sand, hoping my friend would see it whenever he hiked out. Next day, I went back and got the cams and continued tracing the river.

Striated herons, brown dippers, plumbeous redstarts, wagtails, common kingfishers and crested serpent eagles kept us company on our joyful trek out, and macaques and wildlife numerous footprints created the impression of a luxuriously pristine ecosystem.

Having visited Dawushan Nature Reserve several days later on the same trip, there isn’t a doubt in my mind that the Jhiben Gorge has much more of the magical feel that I know from Southeast Asia, and perhaps with a couple dozen camera traps, the clouded leopard can be rediscovered before it is reintroduced.

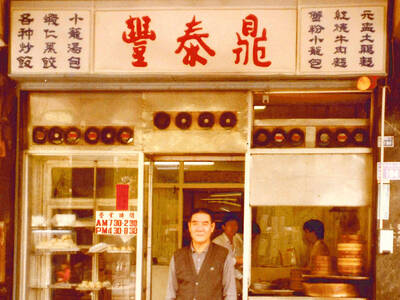

March 24 to March 30 When Yang Bing-yi (楊秉彝) needed a name for his new cooking oil shop in 1958, he first thought of honoring his previous employer, Heng Tai Fung (恆泰豐). The owner, Wang Yi-fu (王伊夫), had taken care of him over the previous 10 years, shortly after the native of Shanxi Province arrived in Taiwan in 1948 as a penniless 21 year old. His oil supplier was called Din Mei (鼎美), so he simply combined the names. Over the next decade, Yang and his wife Lai Pen-mei (賴盆妹) built up a booming business delivering oil to shops and

Indigenous Truku doctor Yuci (Bokeh Kosang), who resents his father for forcing him to learn their traditional way of life, clashes head to head in this film with his younger brother Siring (Umin Boya), who just wants to live off the land like his ancestors did. Hunter Brothers (獵人兄弟) opens with Yuci as the man of the hour as the village celebrates him getting into medical school, but then his father (Nolay Piho) wakes the brothers up in the middle of the night to go hunting. Siring is eager, but Yuci isn’t. Their mother (Ibix Buyang) begs her husband to let

The Taipei Times last week reported that the Control Yuan said it had been “left with no choice” but to ask the Constitutional Court to rule on the constitutionality of the central government budget, which left it without a budget. Lost in the outrage over the cuts to defense and to the Constitutional Court were the cuts to the Control Yuan, whose operating budget was slashed by 96 percent. It is unable even to pay its utility bills, and in the press conference it convened on the issue, said that its department directors were paying out of pocket for gasoline

On March 13 President William Lai (賴清德) gave a national security speech noting the 20th year since the passing of China’s Anti-Secession Law (反分裂國家法) in March 2005 that laid the legal groundwork for an invasion of Taiwan. That law, and other subsequent ones, are merely political theater created by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to have something to point to so they can claim “we have to do it, it is the law.” The president’s speech was somber and said: “By its actions, China already satisfies the definition of a ‘foreign hostile force’ as provided in the Anti-Infiltration Act, which unlike