Feb. 22 to Feb. 28

For 73 years, an imposing gateway leading to the eastern shore of Makung (馬公) praised the people of Penghu for remaining peaceful during the 228 Incident

According to a plaque on the structure, when Taiwan’s population rose up against the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) on Feb. 28, 1947, “only Penghu remained calm.”

Photo: Chen Chih-chu, Taipei Times

After brutally suppressing the incident, the KMT forbade people from discussing the uprising for decades. As a result, it was the only monument throughout Taiwan that mentioned the 228 Incident until activists put one up in Chiayi in 1989 to commemorate the victims.

“Chairman Chiang [Kai-shek (蔣介石)] of the Nationalist Government deeply thanks the people of Penghu for keeping order during the rebellion,” the plaque on the gateway continues, adding that the government rewarded the archipelago with a significant amount of cash in appreciation. Half of it was given to the residents, while the other half was used for various public works, including the gateway.

Native son Mingdi (鳴鏑, real name Sheng Yi-che 冼義哲), is one of many who will immediately point out that the “peaceful” narrative is false. His historical novel, Xiying Paradise: The Penghu Youth Who Resisted During the 228 Incident (西瀛勝境:那群在22八事件抗爭的澎湖青年), was published in June last year, dramatically uncovering the unrest that was buried for decades.

Photo courtesy of Chao Shou-chung

LAND OF NO UPRISINGS

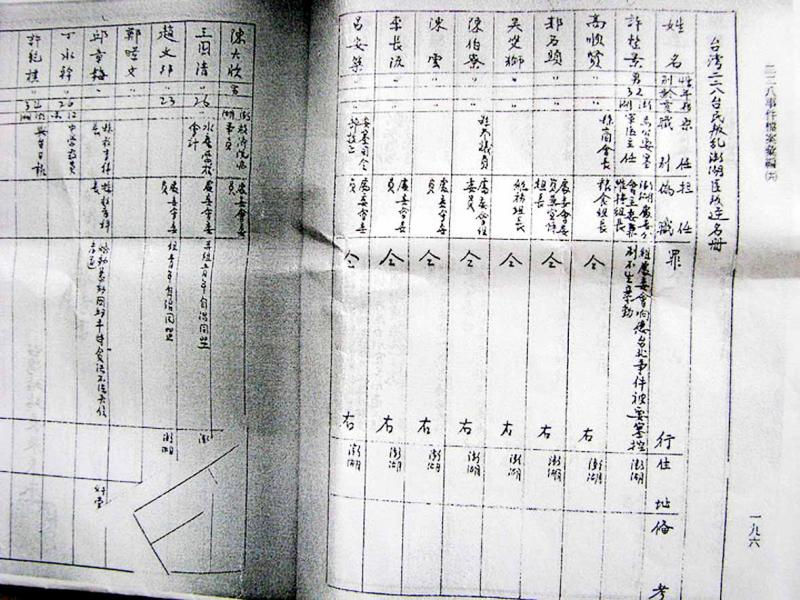

Historian Hsu Hsueh-chi’s (許雪姬) 1996 paper “228 Incident in Penghu” (22八事件在澎湖) is one of the earliest documents to point out that the plaque’s claims were not entirely true.

Historically, Penghu had rarely seen uprisings even during the Qing Dynasty, when there was “one small rebellion every three years, and one large rebellion every five years” in Taiwan. Penghu people rarely participated because it was heavily guarded as a military stronghold, and also because it was too poor and too far from Taiwan to support any major incidents.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

But when the 228 Incident took place, local youth were more than eager to support the cause. The situation was so tense that the Taiwan Garrison Command was afraid to send reinforcements to Taiwan from Penghu out of fear that locals would use the opportunity to rebel, Hsu writes.

Born in 1992, Sheng believed the government narrative about the 228 Incident regarding Penghu until he started doing research on the topic. Most documents simply said that due to the strong military presence and a food shortage, Penghu residents had no choice but to cooperate with the government.

However, one day he found on the Internet a government blacklist of insurgents in Penghu during the 228 Incident — one of them was his granduncle, Chao Wen-pang (趙文邦). He started interviewing local elders, and began his deep dive into the truth.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Like the people in Taiwan, Penghu residents were initially happy to be rid of the Japanese colonizers in 1945, but quickly became disillusioned and resentful under their misrule. After one especially egregious incident, Chao and a few friends spent one night painting anti-KMT slogans around town. Luckily, they were never caught.

Animosity between locals and the government continued to grow in Penghu over inflation, unruly soldiers and other issues before things exploded in Taipei.

TAKING ACTION

News of the uprising quickly spread to Penghu, and Chao and his friends debated what to do.

As the violence spread across Taiwan, governor-general Chen Yi (陳儀) secretly requested help from China while pretending to seek peace. He also ordered the Penghu garrison to send troops and ammunition to suppress the rebels in Kaohsiung.

Penghu remained relatively calm due to the large troop presence. The first bloodshed was when a pregnant woman was accidentally shot as she prepared to head to the hospital. Both she and the baby survived.

The second incident happened when a woman named Chi Shu (紀淑) was shot by troops. Stopped on the street, she didn’t understand what they were asking and ran away, which led to them opening fire. This caused quite a stir as Chi’s father was a respected assemblyman, and coupled with the previous shooting, public anger boiled over.

Thousands surrounded the hospital shouting for justice while Chi underwent surgery. Shih Wen-kuei (史文桂), the military commander on Penghu, personally apologized to the crowd so as to avoid the situation escalating like it had in Taiwan.

But that same day, Chao learned that Shih was ordered to send troops to Kaohsiung, and swore to stop that from happening. Meanwhile, resistance leader Hsieh Hsueh-hung’s (謝雪紅) voice blared through the radio: “The people of Taiwan have risen up against the tyrannical government! Are the people of Penghu still asleep?”

Chao and other young people took action immediately, rushing the police station to steal weapons and ammunition. But the attempt failed. They then turned their attention toward the garrison, but Chi’s father urged the assembled crowd to remain calm as his daughter’s sacrifice was enough.

Sheng writes that Chao’s next step was to stop Shih from sending reinforcements to Kaohsiung. The attempt succeeded, as protesters damage the ship’s propeller, stranding it in Penghu.

In addition to keeping people calm, Shih was also reluctant to send troops to Kaohsiung as it would weaken his forces in Penghu. He convinced Chen Yi that either the ship had malfunctioned or that Penghu was too far to reinforce the violence that was going on across Taiwan, and Chen dropped the matter.

Meanwhile Chao co-formed the Penghu branch of the Taiwan Provincial Self-rule Youth Alliance (台灣省自治青年同盟) to negotiate with the government. At the height of their first rally, gunshots rang out and the crowd quickly dispersed. Over the next two days, Chao and his compatriots were either killed or arrested, Sheng writes.

Curiously, Chao was released after a week, and Shih reported to the central government that the unrest on Penghu was quickly pacified by the help of local elites.

On April 12, Shih gathered the locals and announced that Chiang Kai-shek was rewarding Penghu for their orderly behavior during the incident. Ironically, a portion of the money was used to build a park in honor of Chiang.

Hsu writes that 24 people were implicated in the aftermath, but none were seriously punished.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

With over 80 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of