Jan. 18 to Jan. 24

Viewers couldn’t believe their eyes when the Taipei First Girls’ Senior High School marching band appeared on television in 1981.

None of the girls were sporting the government-mandated hairstyle for female secondary school students, which forbade their hair from going past their neck. Some even had perms.

Photo courtesy of Yang Lien-fu

The students had been invited to perform in the US, which the government saw as an important affair since the US had severed official ties two years earlier. The idea was that sending a group of girls with the same permitted hairstyle would appear contradictory to the “free and democratic” values of the US as well as the image Taiwan was trying to promote, to distinguish it from Communist China.

It caused quite a stir, and newspapers ran editorials wondering if other students would begin to wear their hair long, and even if such restrictions were necessary. Responding to the voices of the students, Guting Girls’ Junior High School (古亭女中) was the first to repeal the restrictions, but the Ministry of Education forced them to reinstate it.

It wasn’t until Jan. 20, 1987, that the government officially removed its restrictions on hairstyles for all secondary school students. However, almost all schools continued to impose their own rules on students’ hair, and punished them for violations.

Photo: Wang Min-wei, Taipei TImes

THE QUEUE QUESTION

Government control over citizen hairstyles had long been a form of social control. The Manchu-style queue, for example, was a symbol of submission to the Qing Empire. Cheng Ke-shuang (鄭克塽), the grandson of Ming Dynasty loyalist Koxinga, was forced to adopt the hairstyle in 1683 when the Qing vanquished his Tainan-based Kingdom of Tungning (東寧), and when peasant Chu Yi-kuei (朱一貴), led a revolt against the Qing in 1721, his men cut off their queues.

When the Qing ceded Taiwan to Japan in 1895, the new colonial masters announced the wearing of a queue as one of “three major Taiwanese backward practices,” along with foot-binding and opium smoking, that needed to be stamped out.

Photo: Shen Hui-yuan, Taipei Times

When prominent tea merchant Lee Chun-sheng (李春生) visited Japan in 1896, locals mocked him as a “pig-tailed slave,” prompting him to become one of the first notable Taiwanese to cut off his queue, lamenting that he had been abandoned by his motherland anyway.

Similarly, other Taiwanese were reluctant to cut off their queue because this symbolized their status as a conquered people.

Writer Chang Shen-chie (張深切) lamented: “Our entire family wept in front of the family altar when we cut our queue. We were deeply ashamed ... that we cut our hair, accepted Japanese education and have become Japanese citizens. I pray that once we chase the Japanese devils out, we can grow our hair back to repay our ancestral spirits.”

By 1915, only about 80,000 men in Taiwan retained queues — mostly old people who were allowed to keep them. For women, the focus was on foot-binding.

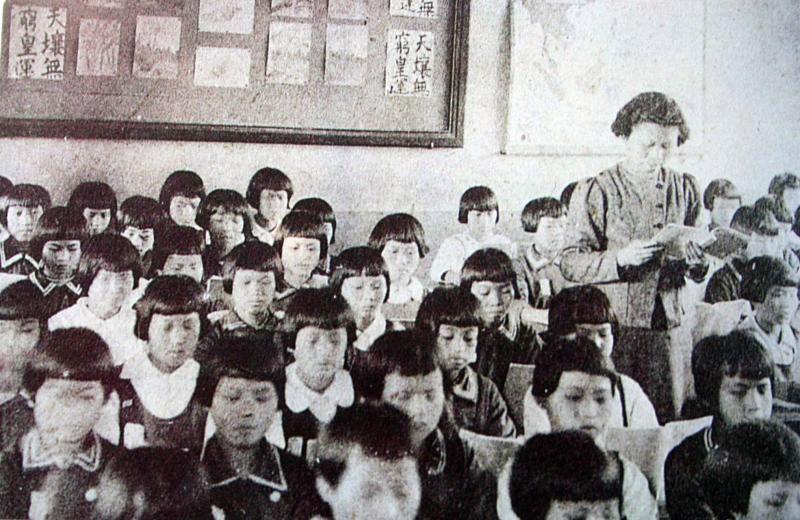

As for schools, students began wearing Western-style uniforms starting around 1920, and a great deal of importance was put on students’ appearance, which presumably included hair. There doesn’t seem to be any specific or unified guidelines, but most boys shaved their heads and girls either wore it short or in braids.

NO HIPPIES ALLOWED

Hair restrictions returned during the Martial Law era — men were forbidden to wear their hair too long, for example. There didn’t seem to be hair rules for women in general (presumably it couldn’t be too outrageous); the authorities were more concerned about them showing too much skin. A 1971 Taiwan TV (台視) clip shows over 100 men who were taken to the police station to be forcefully given haircuts. Curiously, the hair of the men shown in the video can barely be considered “long” by today’s standards.

People, of course, didn’t always follow the law. Taiwan Provincial Assemblyman Tu Yen-ching (涂延卿) in 1978 urged the government to firmly clamp down on “unusual clothes and long hair,” adding that Taiwan should even refuse entry to foreigners who looked like “hippies.”

“The [excessive freedom] in Western countries has perverted the minds of their citizens, causing them to become dispirited, hopeless and confused — which has given to the rise of ‘hippies!’” Tu said. “Their bodies are unkempt, their behavior is odd, they have long hair and wear strange clothes; it’s as if they’ve lost their minds. This has spread to Asia in recent years, and has caused the hearts of our youth to waver as they believe that such behavior is fashionable.”

But most notable were the hair restrictions in schools: In 1950, the Ministry of Education sent the following order to all secondary schools: “Inspections of secondary students have found that many have long hair or varied styles. This is unsightly and a waste of time for the students. In order to promote the values of cherishing time, cleanliness and austerity, we mandate that beginning from this semester, all secondary schools should require that their boys shave their heads and all girls cut their hair short.”

These rules were written into law in 1969, and were again reiterated in 1978.

FREEDOM FOR HAIR

Although government-mandated hair restrictions on secondary school students were officially removed in 1987, almost all schools continued to impose their own rules. Most female high school students were allowed to grow their hair to their shoulders — just a few centimeters longer than before, but opening up a whole new world of styling possibilities.

However, student discontent brewed as society became more open in the 1990s, and more schools relaxed their rules. As the protesting voices grew louder, many public figures also joined in, and students formed an anti-hair restriction association to fight the government.

In July 2005, then-education minister Tu Cheng-sheng (杜正勝) announced that all public schools in the nation should remove their hair restrictions, and on July 23, the activists celebrated with a goodbye-to-hair-restrictions bash.

In response to those who opposed the move, Tu famously asked, “Is the hairstyle issue really that important? Does your hairstyle indicate what kind of person you are? Does wearing one’s hair long make them a bad person?”

The effectiveness of the government lifting the restrictions has been repeatedly questioned. As recent as 2019, 77.5 percent of junior high school respondents to a Humanistic Education Foundation (人本教育文教基金會) survey said that their schools still restricted their hairstyles.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Nine Taiwanese nervously stand on an observation platform at Tokyo’s Haneda International Airport. It’s 9:20am on March 27, 1968, and they are awaiting the arrival of Liu Wen-ching (柳文卿), who is about to be deported back to Taiwan where he faces possible execution for his independence activities. As he is removed from a minibus, a tenth activist, Dai Tian-chao (戴天昭), jumps out of his hiding place and attacks the immigration officials — the nine other activists in tow — while urging Liu to make a run for it. But he’s pinned to the ground. Amid the commotion, Liu tries to

A dozen excited 10-year-olds are bouncing in their chairs. The small classroom’s walls are lined with racks of wetsuits and water equipment, and decorated with posters of turtles. But the students’ eyes are trained on their teacher, Tseng Ching-ming, describing the currents and sea conditions at nearby Banana Bay, where they’ll soon be going. “Today you have one mission: to take off your equipment and float in the water,” he says. Some of the kids grin, nervously. They don’t know it, but the students from Kenting-Eluan elementary school on Taiwan’s southernmost point, are rare among their peers and predecessors. Despite most of

A pig’s head sits atop a shelf, tufts of blonde hair sprouting from its taut scalp. Opposite, its chalky, wrinkled heart glows red in a bubbling vat of liquid, locks of thick dark hair and teeth scattered below. A giant screen shows the pig draped in a hospital gown. Is it dead? A surgeon inserts human teeth implants, then hair implants — beautifying the horrifyingly human-like animal. Chang Chen-shen (張辰申) calls Incarnation Project: Deviation Lovers “a satirical self-criticism, a critique on the fact that throughout our lives we’ve been instilled with ideas and things that don’t belong to us.” Chang

Feb. 10 to Feb. 16 More than three decades after penning the iconic High Green Mountains (高山青), a frail Teng Yu-ping (鄧禹平) finally visited the verdant peaks and blue streams of Alishan described in the lyrics. Often mistaken as an indigenous folk song, it was actually created in 1949 by Chinese filmmakers while shooting a scene for the movie Happenings in Alishan (阿里山風雲) in Taipei’s Beitou District (北投), recounts director Chang Ying (張英) in the 1999 book, Chang Ying’s Contributions to Taiwanese Cinema and Theater (打鑼三響包得行: 張英對台灣影劇的貢獻). The team was meant to return to China after filming, but