Decapitated and eviscerated, the two frogs lay on their backs in a clear broth. Noticing that other diners didn’t hesitate to pile toothpick-thin bones and bits of mottled skin on their tables, I set to work with chopsticks and spoon.

I was winding up a day trip to Beigang (北港), the religious capital of Yunlin County, when I strolled east onto Minjhu Road (民主路) from Wenhua Road (文化路) and came across this eatery. I’d gone to the intersection to see an obelisk that honors the man regarded as Beigang’s founding father.

The Yan Si-ci Pioneering of Taiwan Monument (顏思齊開拓台灣紀念碑) celebrates the arrival in 1621 — or possibly 1622 or 1624 — of Yan Si-ci (顏思齊), a Chinese trader who’d been living in Japan. Some say he left Japan because he took part in an unsuccessful uprising against the shogunate. Others think that changes to the business environment forced him to seek pastures new.

Photo: Steven Crook

Whatever Yan’s motives, the 13-ship convoy he led dropped anchor here. His followers unloaded their supplies, and did their best to establish themselves in a place that the local Aboriginal people called Ponkan.

The new arrivals recorded this toponym as Bengang (笨港, literally “stupid harbor”). It wasn’t until well into the 19th century that this odd place name was replaced by the insult-free Beigang (“north harbor”).

CHAOTIAN TEMPLE

Photo: Steven Crook

I’d begun the day at the house of worship that gives Beigang its cultural and spiritual significance. Chaotian Temple (朝天宮), founded in 1694, is a key center of the Matsu cult. The pious come from all over southern and central Taiwan to pray to the sea goddess. However, because of a falling out between the leaders of Chaotian Temple and those in charge at Dajia Jenn Lann Temple (大甲鎮瀾宮), the famous annual multi-day pilgrimage that honors Matsu each spring no longer passes through Beigang.

Yet Chaotian Temple has something Jenn Lann Temple lacks: An iron nail embedded in a slab of granite. In the very center of the shrine, steel railings cordon off part of a step. Within, a circle of red paint surrounds the almost-invisible head of a 200-year-old handmade nail.

A Chinese-language panel attached to the railings says that “a native of Quanzhou in Fujian, a filial son surnamed Xiao (蕭),” had sailed to Taiwan with his mother to search for his father. As they disembarked on the shore near Beigang, a freak wave caught the pair. The young man was rescued, but there was no trace of his mother.

Photo: Steven Crook

Xiao prayed to Matsu for her help, saying: “If this nail penetrates the stone, the goddess will protect my parents.” It did, and — the faithful believe — she did. Xiao was soon reunited with his mother, and they eventually tracked down his father.

From Chaotian Temple, I marched north 1.9km to a far newer yet even bigger religious complex.

WUDE TEMPLE

Wude Temple (武德宮) is the legacy of a pious individual named Chen Mao-lin (陳茂霖), who moved to Beigang in 1955 to take over a herbalist’s practice. He prospered until 1963, when his wife fell into a coma. Neither practitioners of traditional Chinese medicine nor doctors trained in “Western” scientific medicine were able to cure her.

Desperate for answers, Chen took a deep dive into popular religion. He offered incense to the gods every morning and evening. (The temple’s Web site notes that Mrs Chen herself came from a Christian family, and “would never have thought of resorting to ghosts and gods.”)

After his wife recovered, Chen became convinced that the supernatural entity who’d helped him was Zhao Gongming (趙公明), a military god of wealth. Zhao is regarded as the “central direction” of the Five Directions Wealth Gods (五路武財神). All five are now enshrined in Wude Temple, alongside Zhao’s parents and three sisters, the Jade Emperor (玉皇大帝) and several other deities.

The first edition of Wude Temple proved too small to accommodate the busloads of faithful who arrived on weekends and holidays, so Chen donated the current site at 330 Huasheng Road (華勝路).

Construction began in 1969, but several parts of the complex are far newer, and fabulously ornate. It’s as if the management committee sought the best temple that money could buy. It’s also unusually clean — only the central chamber displays the layers of soot often seen in popular shrines.

From Wude Temple, I wandered back to the downtown via Beigang Daughters Bridge (北港女兒橋). This curved steel footbridge goes across the Beigang River (北港溪), strangely without providing access to the other side. Even so, it’s a worthwhile detour if you want to see the narrow-gauge railroad that used to carry cane to Beigang’s now-shuttered sugar refinery.

I had one more religious landmark, and some colonial-era infrastructure, to look at before I could sup on frog soup.

YIMIN TEMPLE

Every time I’m in Beigang, I return to Yimin Temple (義民廟) at 20 Jingyi Street (旌義街), which some bilingual signs call the Militia Shrine. It’s far more peaceful than Chaotian Temple, and I’m always wondering when they’ll update the information panel by the entrance and include what is, to my mind, the most interesting aspect of this shrine’s history.

The story begins during the Lin Shuangwen Incident (林爽文事件), a 1786-1788 uprising against Qing Dynasty rule. To resist the rebels, many settlements formed militia units.

Beigang’s defenders fought off several incursions, aided by a brave and vigilant dog, but one night their luck ran out. As well as massacring 108 militiamen (because this number is of great significance in Taoism, it might be a later embellishment, not an accurate tally), Lin’s followers killed the dog.

Community leaders buried the human dead in a common grave, beside which they later established this temple. Another mass grave, on the other side of the building, is the final resting place of militia members killed during the Dai Chaochun Incident (戴潮春事件) of 1862-1864.

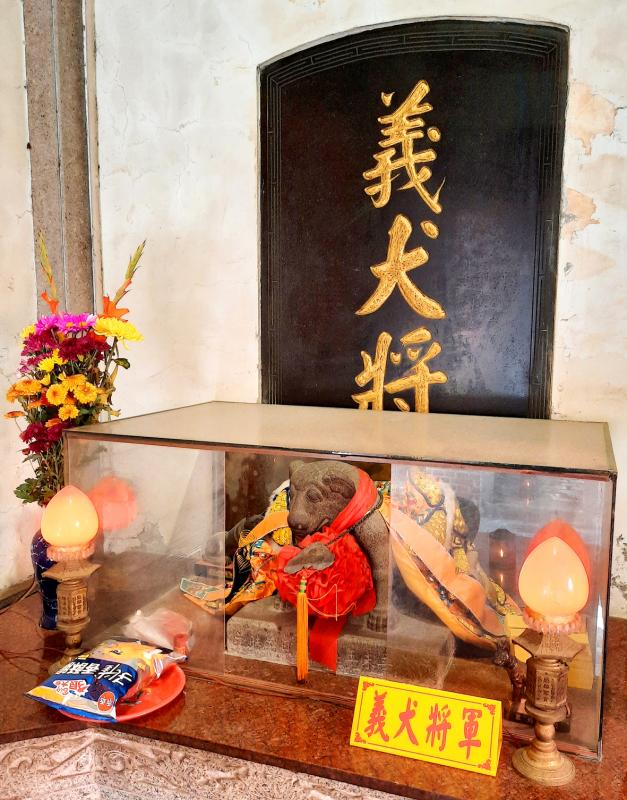

Strangely, the bilingual introduction visitors pass as they enter the temple’s grounds makes no mention of the canine, that it’s entombed at the back of the shrine and that it’s worshipped here as the Righteous Dog General (義犬將軍). A small statue of the dog is honored in a rear chamber. Like many temple effigies, it wears an embroidered cape.

Walking from Yimin Temple to Beigang Water Cultural Park (北港水道頭文化園區), on the corner of Minsheng Road (民生路) and Shueiyuan Street (水源街), took me through the oldest part of Beigang.

This neighborhood doesn’t quite match Anping (安平) in Tainan or Lukang (鹿港) in terms of visible antiquity, but it’s not without points of interest. One is the 19th-century Jar Wall (甕牆), a remnant of the home of a merchant who shipped rice and sesame oil to Fujian. Vessels returning empty to Taiwan often carried bricks or wine jars as ballast, and the merchant decided to use some as building materials, apparently to remind the younger generation that the family’s wealth was a result of astute trading.

I prefer the functional elegance of the 18.2m-tall water tower in Beigang Water Cultural Park. Unusually, the lower section is decagonal, while the upper part is cylindrical.

AND THE FROGS?

If you’ve read this far because you want to know how the frogs tasted, your wait is over. They were edible yet not delicious. The meat was slightly greasy, but the hot liquid, flavored with ginger and basil, washed the lingering pungency of incense from my mouth and throat. Just the thing after a temple tour.

Steven Crook has been writing about travel, culture and business in Taiwan since 1996. He is the author of Taiwan: The Bradt Travel Guide and co-author of A Culinary History of Taipei: Beyond Pork and Ponlai.

Feb. 17 to Feb. 23 “Japanese city is bombed,” screamed the banner in bold capital letters spanning the front page of the US daily New Castle News on Feb. 24, 1938. This was big news across the globe, as Japan had not been bombarded since Western forces attacked Shimonoseki in 1864. “Numerous Japanese citizens were killed and injured today when eight Chinese planes bombed Taihoku, capital of Formosa, and other nearby cities in the first Chinese air raid anywhere in the Japanese empire,” the subhead clarified. The target was the Matsuyama Airfield (today’s Songshan Airport in Taipei), which

China has begun recruiting for a planetary defense force after risk assessments determined that an asteroid could conceivably hit Earth in 2032. Job ads posted online by China’s State Administration of Science, Technology and Industry for National Defence (SASTIND) this week, sought young loyal graduates focused on aerospace engineering, international cooperation and asteroid detection. The recruitment drive comes amid increasing focus on an asteroid with a low — but growing — likelihood of hitting earth in seven years. The 2024 YR4 asteroid is at the top of the European and US space agencies’ risk lists, and last week analysts increased their probability

For decades, Taiwan Railway trains were built and serviced at the Taipei Railway Workshop, originally built on a flat piece of land far from the city center. As the city grew up around it, however, space became limited, flooding became more commonplace and the noise and air pollution from the workshop started to affect more and more people. Between 2011 and 2013, the workshop was moved to Taoyuan and the Taipei location was retired. Work on preserving this cultural asset began immediately and we now have a unique opportunity to see the birth of a museum. The Preparatory Office of National

On Jan. 17, Beijing announced that it would allow residents of Shanghai and Fujian Province to visit Taiwan. The two sides are still working out the details. President William Lai (賴清德) has been promoting cross-strait tourism, perhaps to soften the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) attitudes, perhaps as a sop to international and local opinion leaders. Likely the latter, since many observers understand that the twin drivers of cross-strait tourism — the belief that Chinese tourists will bring money into Taiwan, and the belief that tourism will create better relations — are both false. CHINESE TOURISM PIPE DREAM Back in July