Dec. 21 to Dec. 27

A historic decision was made on Dec. 19, 1986 when the National Taiwan University (NTU) student council voted 83-0 to abolish school censorship of student publications.

The publications’ faculty advisers still had to inspect the contents and were allowed to attach any conflicting opinions at the end of each article, but the school could no longer stop the students or punish them for publishing content that they, and by extension the government, didn’t approve of.

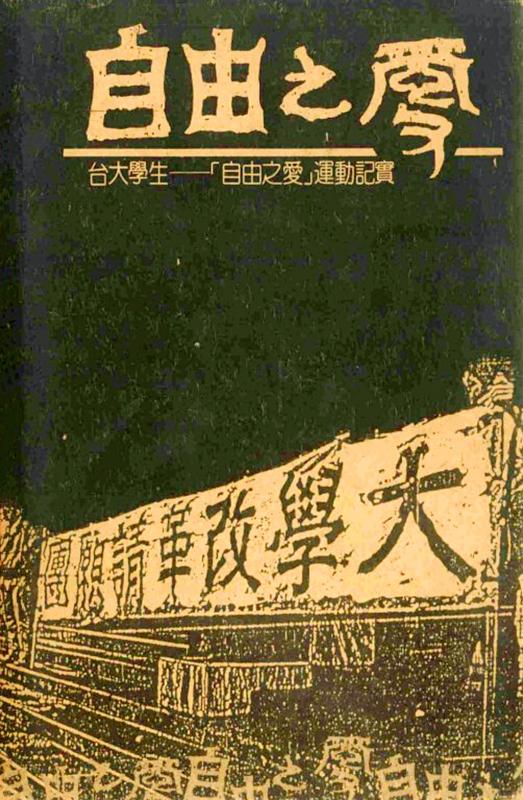

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The months-long struggle, dubbed the Love of Freedom Movement (自由之愛運動), didn’t end there. On Dec. 22, the second issue of the Love of Freedom campus publication called for complete reform of the university system, including freedom of assembly, academic freedom, university autonomy for professors and students and for complete government withdrawal from school affairs.

It was a bold statement given that martial law was still in effect, and the students put on seven public speeches over the following 10 days while government agents watched carefully. By the final event, 1,865 students had signed the university reform declaration.

Although the government shot down Love of Freedom’s demands when about 50 members marched to the Legislative Yuan on March 24, it was a significant milestone that foreshadowed the vibrant student movements of the 1990s.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

Teng Pi-yun (鄧丕雲) writes in his book, A History of Taiwan Student Movements in the 80s (80年代台灣學生運動史) that although student groups began campaigning for their rights as well as other social issues at the turn of the decade, the Love of Freedom movement was the first large-scale student protest that caught the public’s attention.

“In that era, it was ‘Love of Freedom’ that made the public realize, ‘Taiwan also has student movements now!’” Teng writes, adding that the spirit of the movement “fit in with the public image of students as idealistic, passionate and brave young people.”

GROWING UNREST

Taipei Times File Photo

Campus voices were silenced for decades after student protests over police brutality on April 6, 1949 led to mass arrests and several alleged executions. But as the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) iron grip on the country loosened and the political situation shifted in the late 1970s, students began speaking out again.

During the early 1980s, campus activism was limited to unorganized small groups who called for more freedom of expression through underground posters, graffiti and campus rallies and speeches. But publications were still subject to censorship by school officials, and offenders could be suspended and even shut down.

The call for direct student elections began in 1982 and came to a head on May 11, 1985, when students staged a march and engaged in a shouting match with school officials at the campus entrance. The school denied their request, but unrest exploded again exactly a year later when Lee Wen-chung (李文忠), one of the leaders of the march, was expelled. The school insisted that it was over poor grades but the students were unconvinced. They staged protests — including hunger strikes under the iconic Fu Bell — for over a week, culminating in violent clashes with campus police. The school refused to rescind its decision, and protest leaders were placed on probation.

Photo: Liao Chen-huei, Taipei Times

The Lee Wen-chung Incident, as it is now known, was an important watershed for NTU’s student movement, as the students gained a clearer picture of the consequences of their actions and how far they could push things. Not only did it embolden more students — including those in other schools — to participate, it also showed that the officials were not willing to negotiate.

Just four months later, NTU suspended the school’s journalism club for including in the school paper discussions on the Lee Wen-chung Incident and criticizing government interference in campus elections. The students refused to accept this, and this time even more groups chimed in on the outcry. Twelve major campus publications, including prestigious academic ones, issued a joint declaration of campus freedom of speech on Oct. 12 to show their support.

On Oct. 24, the journalism club held a farewell ceremony at the main gate of NTU titled, “Speeches on the Love of Freedom: We Want Freedom of Speech on Campus” despite government and school objections, disseminating the message through clandestine fliers. Around 5pm, members tied yellow ribbons on coconut trees lining the entrance and people slowly gathered to the protest songs of Joan Baez.

Campus officials watched warily, but allowed the event to continue in peace.

FINAL SHOWDOWN

The voices of dissent grew louder over the following month. More than 50 student groups signed a freedom of speech declaration, and 128 graduate students issued a separate declaration shortly afterward.

On Human Rights Day, Dec. 10, the protesters released the underground publication Freedom of Love and put on a series of speeches. The school tried to stop them by blocking the grounds with a garbage truck, but with nearly 800 students on scene, there was little they could do.

Although the students rode the momentum after defeating school censorship and marched to the Legislative Yuan on March 24 to deliver their petition, the government promptly said no. According to Teng, then-education minister Lee Huan (李煥) told legislators that afternoon he was saddened by the petition and suggested that NTU communicate with the students about their behavior instead.

Dejected, Love of Freedom leaders retreated back to campus, refocusing on gaining more clout with the student association. Teng writes that despite the government’s stance, things were changing on campus as KMT influence waned. The school’s party office moved off campus, and its student KMT organization, which had dominated the student association for over a decade, was in turmoil and announced that they would not run a candidate for association head. The school seemed to relax some of its rules, allocating space for public speeches and enacting rules on marches and gatherings, but Teng doubts the sincerity of these moves since the conditions were stringent and unrealistic.

On May 11, 1987, exactly two years after the march for direct student elections and a year after a mass sit-in over the Lee Wen-chung Incident, Love of Freedom held its final parade. About 60 students marched through campus singing songs such as Formosa (美麗島) and Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風) while chanting the 1985 slogans of “direct elections” and “I love NTU!” They then held a series of speeches while handing out fliers espousing their ideals. May 11 is now observed as NTU Student Day (台大學生日).

The school was angry and planned to severely punish the participating students, but under immense social pressure, only seven students received minor demerits. In June, the new student association, now led by those advocating reform, held its first assembly to continue the mission of obtaining student autonomy — and Love of Freedom quietly faded into history.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,