“You were colonized a long time before us yet the pain never lessens. Even if the methods were just as brutal and last a longer time,” Maori writer Gerry Te Kapa Coates writes to Taiwanese Aborigines in the poem, Walking in Your Shoes — We the Colonised Unite.

The indigenous peoples of Taiwan and New Zealand share a common Austronesian ancestry, and it’s widely believed that the Austronesian migration to New Zealand, Southeast Asia and the Pacific originated in Taiwan. There have been rich exchanges between the two groups in recent years, but Anton Blank, founder of Ora Nui, New Zealand’s only Maori literary journal, says the connection is still seldom discussed in his home country.

That’s why he united the two related peoples with a shared history of colonization in Ora Nui’s fourth issue, following a collaboration with Australian Aborigines in the third.

Photo courtesy of Ora Nui

Published earlier this month, the journal intersperses Maori pieces with works by Taiwanese writers and artists either of Aboriginal heritage or who focus on Aboriginal topics. The entries are divided into three sections: visual arts, poetry and short fiction; Austronesian studies; and creative non-fiction and essays, with authors not separated by country of origin or ethnicity, but organized alphabetically so the readers can make their own connections.

Several big name Aboriginal creatives contributed to the issue, such as Puyuma novelist Badai, “ocean literature” heavyweight Syaman Rapogan of the Tao people, former Council of Indigenous Peoples minister and Control Yuan vice-president Paelabang Danapan, and Paiwan craftsman and artist Sakuliu Pavavaljung, who has been tapped to represent Taiwan at next year’s Venice Bienniale.

But there’s also emerging talent, especially in the visual arts, and fascinating studies on topics such as tracking the Austronesian migration through paper mulberry and translating Native American Chief Seattle’s speech into the Seediq language. It also provides a rich glimpse of Maori writing and how differently from their Taiwanese counterparts do they focus on their identity, deal with colonization and modernization as well as step out of the box to explore diverse topics such as gender and science fiction.

Photo courtesy of Biung Ismahasan

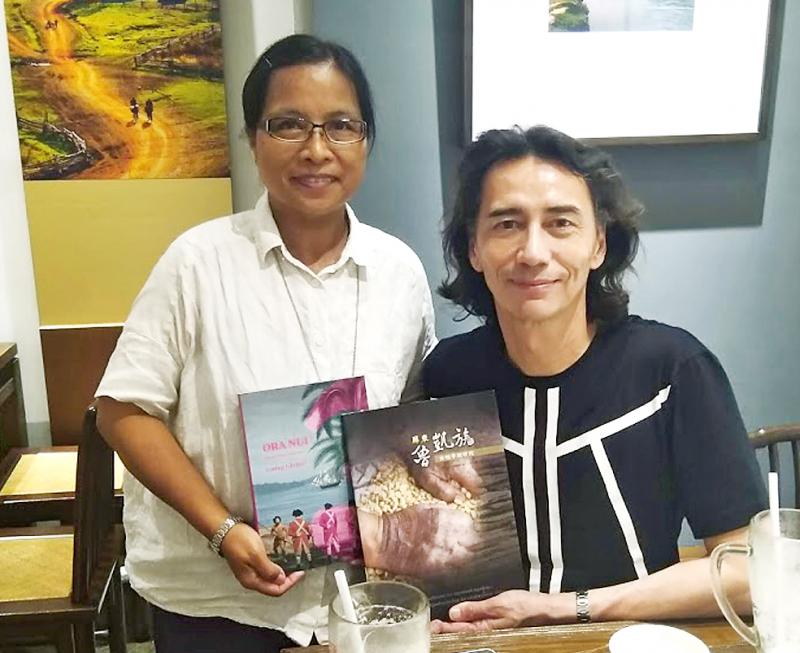

Su Shin (蘇欣), who became interested in the issue after working with Aboriginal artists through her publishing job, met Blank about three or four years ago at the Taipei Book Fair. Blank had been wanting to do a collaborative issue between Taiwan and New Zealand, and Su quickly signed up for the arduous task and obtained support from the Ministry of Culture.

Su was in charge of recruiting and editing work from the Taiwanese side. While the authors were not asked to respond specifically to the Austronesian connection with the Maori, she could see some common themes.

“It wasn’t so much about the direct relationship to the Maori,” she says. “We try to have contributors write whatever they feel like. But when you read a few stories together, this idea of different generations with different beliefs, political and personal ideologies emerges; the fragmentation within a family … is a repetitive theme in general.”

Photo courtesy of Su Shin

The academic section focuses more directly on the connections between the Taiwanese Aborigines and the Maori, from tracing the migration to examining parallels in decolonization to comparing the Maori film Utu with Taiwan’s Seediq Bale, both of which feature indigenous people rising up against the colonizers.

Blank, on the other hand, honed in more on the differences between the two groups.

“That’s what I found working with different indigenous groups — we have the common identity of being indigenous but the context of each situation is so different that we express ourselves very differently,” he says. “We’re concerned about the same issues such as colonization, and New Zealand and Australians write much about it — but it wasn’t as present in the Taiwanese [writing].

With the Australians, for example, Blank noticed a much stronger sense of pain and dislocation in the writing even compared to the Maori pieces, which are becoming increasingly diverse and modern.

“If I had to compare the two, in the [Australian] Aboriginal issue there was a visceral pain of their colonial experience,” Blank says. “I don’t have the same sense of grief in the Taiwanese writing.”

Blank adds that he felt that the Taiwanese writing was quite ethereal, with a heavier dose of magic realism compared to Maori writing. What’s common — and Blank saw this even in the European writing — is the exploration of existential issues and the search for identity and one’s place in the world.

While the Maori are native English speakers, translating the Taiwanese works from Chinese to English was a gargantuan task, Su says.

“With really good literary translations, the translator has to recreate the writing [so it is natural to] the target language,” she says. But because the content is indigenous, when the translator tries to rewrite it, he or she has to “think about whether it gives a colonial perspective.”

“Are you trying to colonize and whitewash it by ignoring the original language and structure?” Su says. “There’s a lot of cultural things you have to think about and discuss with the contributors, but they aren’t all English speakers so they can’t always be relevant in the discussion.”

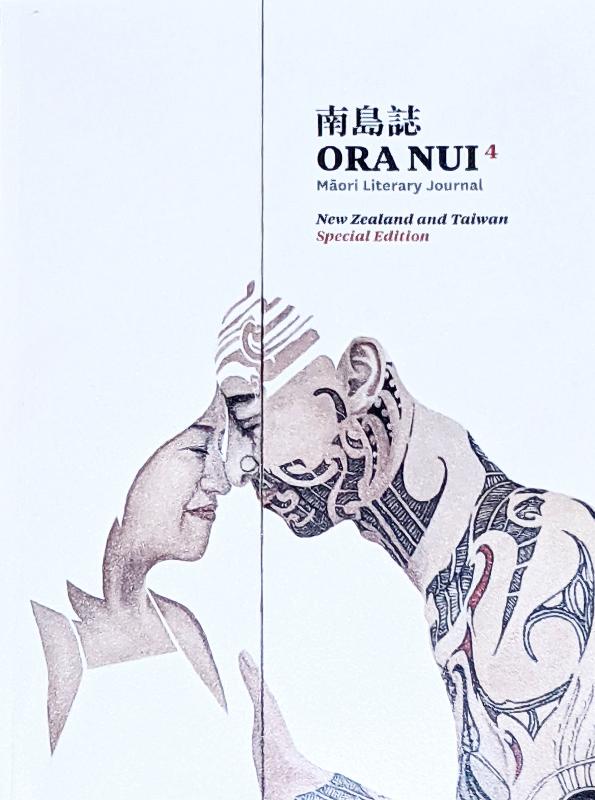

The cover piece by Idas Losin, who is Atayal and Truku, features a fully-tattooed Maori man performing a traditional hongi greeting with an indigenous Taiwanese woman. Atayal and Truku women traditionally tattooed their faces as well, but the last Atayal woman with facial tattoos died last year — whereas the Maori ta moko tattoos have seen a resurgence since the 1990s.

“Idas met George, a Maori artist, and she thought [his tattoos] were so beautiful and she was so amazed, but she also felt that a part of her culture was lost,” Su says. George also greeted everyone with the hongi and after he did so with Idas, she was moved to create the painting.

“This image is so symbolic of the journal,” Su says.

While global attention is finally being focused on the People’s Republic of China (PRC) gray zone aggression against Philippine territory in the South China Sea, at the other end of the PRC’s infamous 9 dash line map, PRC vessels are conducting an identical campaign against Indonesia, most importantly in the Natuna Islands. The Natunas fall into a gray area: do the dashes at the end of the PRC “cow’s tongue” map include the islands? It’s not clear. Less well known is that they also fall into another gray area. Indonesia’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) claim and continental shelf claim are not

Hourglass-shaped sex toys casually glide along a conveyor belt through an airy new store in Tokyo, the latest attempt by Japanese manufacturer Tenga to sell adult products without the shame that is often attached. At first glance it’s not even obvious that the sleek, colorful products on display are Japan’s favorite sex toys for men, but the store has drawn a stream of couples and tourists since opening this year. “Its openness surprised me,” said customer Masafumi Kawasaki, 45, “and made me a bit embarrassed that I’d had a ‘naughty’ image” of the company. I might have thought this was some kind

“Designed to be deleted” is the tagline of one of the UK’s most popular dating apps. Hinge promises that it is “the dating app for people who want to get off dating apps” — the place to find lasting love. But critics say modern dating is in crisis. They claim that dating apps, which have been downloaded hundreds of millions of times worldwide, are “exploitative” and are designed not to be deleted but to be addictive, to retain users in order to create revenue. An Observer investigation has found that dating apps are increasingly pushing users to buy extras that have been

What first caught my eye when I entered the 921 Earthquake Museum was a yellow band running at an angle across the floor toward a pile of exposed soil. This marks the line where, in the early morning hours of Sept. 21, 1999, a massive magnitude 7.3 earthquake raised the earth over two meters along one side of the Chelungpu Fault (車籠埔斷層). The museum’s first gallery, named after this fault, takes visitors on a journey along its length, from the spot right in front of them, where the uplift is visible in the exposed soil, all the way to the farthest