The first thing you need to know about Green Island is the 60 minute boat ride over. Only experience prepares you for it — and even then, you are going to suffer.

“Okay, time to go to sleep,” one of my traveling companions tells me, as the packed ferry pulls out of the Taitung City port.

Yeah, that’s a good one. Minutes out, the waves are smashing the boat with such fury that I fear the creaking hull isn’t going to fulfill its engineered purpose.

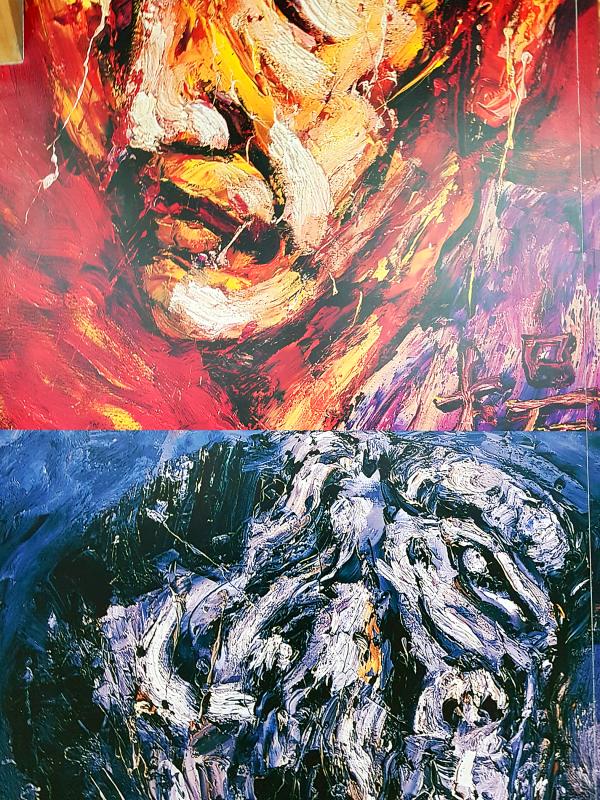

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

As the ferry violently heaves up and down, the rustle of plastic bags, which hang from red poles like limp bodies, becomes unmistakable. And then it begins, the discordant symphony of sick.

I had imagined that sea legs are something you know you have within a few minutes of hitting the water. They are not. It’s cumulative. You may arrogantly think that 15 minutes into the sail that you are home free. You are not. A passenger sitting close to me seemed to have that in mind as he scrolled through his mobile phone. After 30 minutes, he was barfing in his bag.

I was fortunate. Partly, I suspect, because I have a natural disposition to not getting motion sickness on a boat. More likely, however, it’s because a colleague spent a great deal of time a week before the trip scaring the hell out of me about how bad it can be.

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

Take motion sickness medication, he said. Eat as little as possible in the hours before departure. Avoid alcohol on the day and night before. Sit as far to the back of the boat as you can. Close your eyes and, like my fellow traveler next to me said, try to sleep — or at least relax. I felt kind of foolish that I hadn’t thought of this myself. But it turns out few people prepare. Of the five of us who traveled down from Taipei, I was the only one who had bothered to buy sea sickness medication. Thankfully, the package contained 10 tablets.

For such a torturous trip (and the Taitung government should really subsidize larger ferries), why do so many people bother to visit Green Island? In addition to the hot springs dating back to the Japanese colonial era and extensive water sports, the White Terror Memorial Park and Green Island Human Rights Memorial Park are certainly worth the ferry trip over (you can fly there, but it’s difficult to book a seat).

DARK TOURISM

Photo: Hsu lee-chuan, Taipei Times

It seems appropriate that we should suffer on the journey over. It put us in the proper state of mind to understand, if only slightly, the suffering of the estimated 20,000 political prisoners who were sent to Green Island for the majority of the White Terror era (1949 to 1992) under the rule of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) regime.

Between 140,000 to 200,000 people — many of whom were from the intellectual and social elite — were imprisoned throughout Taiwan after the KMT lost the Chinese Civil War and fled here in 1949.

To consolidate its authoritarian rule, the government rounded up suspected “communist sympathizers” and others seen as a threat to the regime, disappearing them in prisons throughout the nation. Those imprisoned on Green Island found themselves either at the New Life Correction Center (新生訓導處) from 1951 to 1965, or the Reform and Education Prison (感訓監獄), also known euphemistically as Oasis Village (綠洲山莊), from 1972 to 1987.

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

Inmates experienced torture, beatings and forced labor in a system that political prisoner Huang Kuang-hai (黃廣海) described as “a concentration camp.”

After the prisons shut down in the late 1980s, it wasn’t clear what would happen to these symbols of repression. As late as 1999, human rights activists were lamenting that the government was refusing to remove the padlocks and open up the doors on this dark side of Taiwan history.

Shih Ming-teh (施明德), a democracy activist who was imprisoned on Green Island at the age of 21 for almost a quarter century, echoed in November 1999 the sentiment of many when he said of Oasis Village that “preserving [it is] very important. Whether you like it or not, it is a part of our history and should not be forgotten.”

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

Two decades later, Green Island White Terror Memorial Park (白色恐怖綠島紀念園區) opened the doors to a dark chapter in Taiwan’s authoritarian past.

Those who passed through the Green Island, as well as the Jing-Mei White Terror Memorial Park (白色恐怖景美紀念園區) in New Taipei City, reads like a who’s who of Taiwan’s democracy and human rights activists. Prominent human rights author Bo Yang (柏楊), democracy pioneers Peng Ming-min (彭明敏) and Huang Hsin-chieh (黃信介) and former vice president Annette Lu (呂秀蓮) were all imprisoned for their activism.*

PENAL COLONY

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

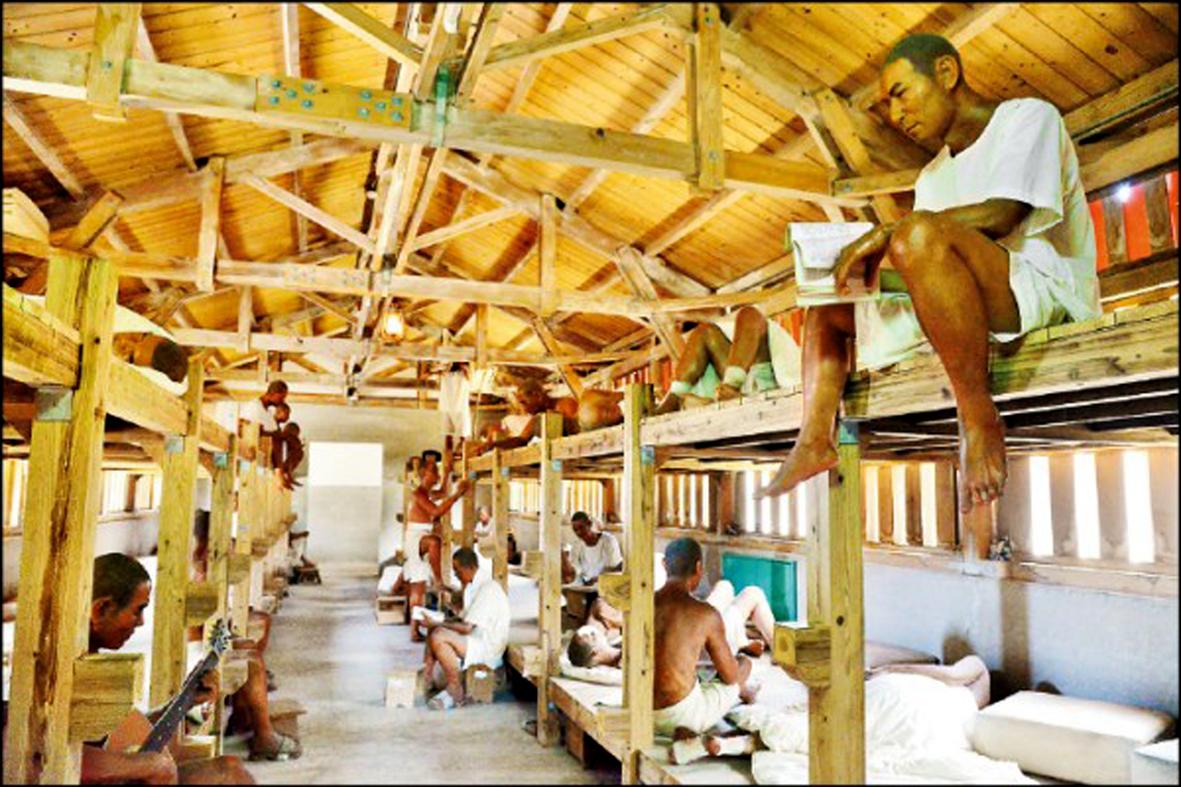

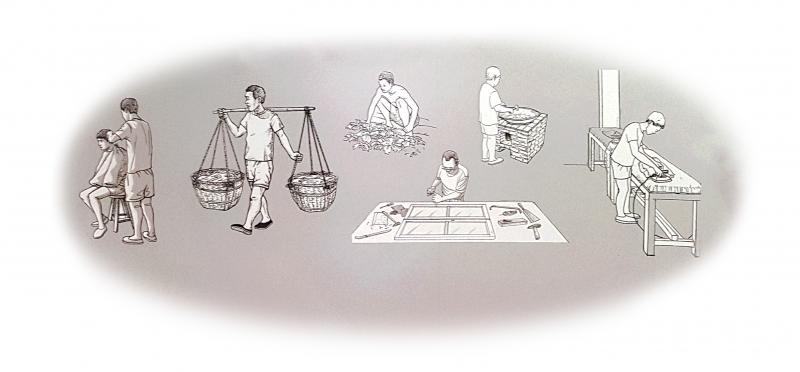

Life in the penal colony is depicted by life-like wax figures displayed at New Life Correction Center. The four bungalows that make up the nucleus of New Life have today been turned into exhibition halls, each containing superb thematic exhibits that are remarkable in their detail and nuanced in their depiction.

Expect to spend several hours here viewing the many exhibits of prison life, watching the documentaries of those who were executed and examining documents and pictures of the inmates and black-and-white photos of female prisoners — known as the “women’s squad” — and the parade grounds.

We are not only shown how these prisoners were dehumanized, but also how they retained their humanity. One building, themed “thought and labor reform,” brings to life the ways authorities exhausted prisoners through hard labor to make them mentally pliable. One scene shows men using sledge hammers to smash up rock that would be used in construction projects; another depicts a group of men receiving ideological training, while a third shows a man beneath a thatched roof surrounded by chickens and pigs that he is in the process of feeding (inmates were allowed to raise animals and grow vegetables).

Photo: Hsu lee-chuan, Taipei Times

Another building freezes in time the dorm cells where “New Lifers” lived when not doing back-breaking work or forced to learn about the revolution against communism. One wax mannequin shows a man, dressed in a loincloth, moving a chess piece; another plays a violin; others are sitting reading or writing. The exhibition makes clear that the one hour they are given before lights out is the only time they have to regain some semblance of their humanity.

Before heading to Oasis Village, be sure to visit the monument at the Human Rights Memorial Park with its unobstructed views of the ocean. It features the engraved names of political prisoners and the dates that the victim was executed or to the years of imprisonment.

Oasis Village, located 1km from New Life, offers visitors a different, somewhat more dreary, view of prison life. Whereas the wooden bungalows that make up New Life emphasized the day-to-day tasks of inmates, Oasis confronts the visitor with the drudgery of prison life: towering stone walls emblazoned with slogans and topped with razor wire, the “Eight-Sided Building (watching four corridors),” with its individual cells and solitary confinement, that overlooks a central courtyard.

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

Slogans such as “Love your homeland! Love your country! You must oppose communism!” remind visitors that these prisons were born out of Cold War ideological struggles between Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) and Mao Zedong (毛澤東), North Korea and South Korea, the US and the USSR, the Vietnam War.

The focus at Oasis is on incarceration. How could it not be, when the “Eight-Sided Building” housed hundreds of inmates, the claustrophobia easy enough to image as you wander through the long deserted halls.

I spent a few moments in a building devoted exclusively for cells for solitary confinement, a place where Shih says he would spend a total of thirteen years.

I walked away from the museum impressed in the effort taken to reconstruct its history — a testament to Taiwan’s willingness to scrutinize its past, not as victims but as those trying to come to terms with a dark period in the nation’s history.

It turns out that the boat ride wasn’t so arduous after all.

* An earlier version of this story incorrectly said that Peng, Huang and Lu were imprisoned on Green Island. They were imprisoned in Jing-mei. The Taipei Times regrets the error.

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invaded Vietnam in 1979, following a year of increasingly tense relations between the two states. Beijing viewed Vietnam’s close relations with Soviet Russia as a threat. One of the pretexts it used was the alleged mistreatment of the ethnic Chinese in Vietnam. Tension between the ethnic Chinese and governments in Vietnam had been ongoing for decades. The French used to play off the Vietnamese against the Chinese as a divide-and-rule strategy. The Saigon government in 1956 compelled all Vietnam-born Chinese to adopt Vietnamese citizenship. It also banned them from 11 trades they had previously

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

Jan. 12 to Jan. 18 At the start of an Indigenous heritage tour of Beitou District (北投) in Taipei, I was handed a sheet of paper titled Ritual Song for the Various Peoples of Tamsui (淡水各社祭祀歌). The lyrics were in Chinese with no literal meaning, accompanied by romanized pronunciation that sounded closer to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) than any Indigenous language. The translation explained that the song offered food and drink to one’s ancestors and wished for a bountiful harvest and deer hunting season. The program moved through sites related to the Ketagalan, a collective term for the

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan