Red brick has been a key feature of Taiwan’s built environment since the 1895-1945 period of Japanese rule. The elegance of several colonial-era landmarks — including the Red House (西門紅樓) in Taipei’s Ximending and Kaohsiung’s Wude Hall (高雄武德殿), also known as Takao Butokuden — derives in large part from the use of red bricks in conjunction with concrete.

Possibly the oldest red-brick building standing in Taiwan is Oxford College (牛津學堂). Commissioned by George Mackay, a Presbyterian missionary from Canada, it was completed in 1882. It’s now a museum on the campus of Aletheia University (真理大學), in a neighborhood dotted with century-old red-brick structures in New Taipei City’s Tamsui District (淡水).

During the Japanese era and for some years afterward, few people could afford to build a house entirely of bricks. Even now, in the countryside it isn’t difficult to find single-storey abodes where the external walls are brick from ground level to waist height only. The upper section is sometimes wood, but more often wattle (a woven lattice of bamboo slats) and daub (a mixture of mud, rice husks, and pig dung).

Photo: Steven Crook

By the time central Taiwan was ravaged by catastrophic floods in August 1959, the country had become somewhat more prosperous. Rebuilding efforts began as soon as the waters receded, but were stymied by a shortage of bricks.

Even though the authorities urged brickworks to step up production, huge demand caused brick prices to rise. Seeing an opportunity, the founders of what’s now called Jinshuncheng Bagua Kiln (金順成八卦窯) in Changhua County’s Huatan Township (花壇) established a new brickworks on a plot of land 1.5km east of Huatan Railway Station.

The Huatan area has the right kind of clay for making bricks, and Jinshuncheng Bagua Kiln was neither the first nor the last brickworks to operate in the township. The “bagua” in its name comes from its shape, which is said to resemble the common octagonal depiction of the Eight Trigrams (symbols used in Taoist cosmology).

Photo: Steven Crook

NOTABLE LANDMARK

As far as industrial-heritage enthusiasts are concerned, this landmark is notable because it’s the last remaining Hoffmann-type kiln in central Taiwan.

This design, patented by Friedrich Hoffmann of Germany in 1858, makes it possible to fire bricks nonstop. For this reason, these brickworks are sometimes called “Hoffmann continuous kilns.”

Photo: Steven Crook

Previously, an entrepreneur operating a traditional kiln had to waste several days loading it with unfired bricks before the firing process could begin. Loading can never be rushed, as ware has to be stacked in a way that makes efficient use of the available space, yet not so tightly that hot air can’t circulate.

In a Hoffmann-type brickworks, a fire is kept burning in the central oblong bunker, fuel being added through hatches on the roof. Jinshuncheng Bagua Kiln ran mainly on timber from the forests in Taiwan’s interior. Wood scraps and rice chaff were secondary fuels.

Heat was directed to whichever part of the tunnel-like wraparound chamber needed it. Partitions weren’t necessary: When full heat was being applied to one batch of bricks (typically 1,700 to 1,800 for this kiln), heat escaping to one side ensured that a just-fired batch didn’t cool too quickly, while hot air drifting to the other side slowly preheated the next batch.

Photo: Steven Crook

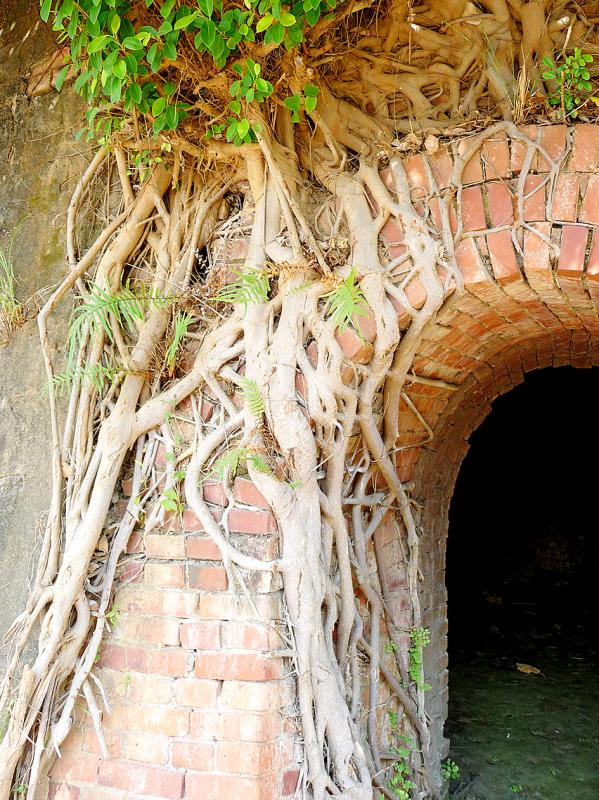

Bricks were loaded and removed through 22 arched apertures on the sides. Most are intact, and through them explorers can access the kiln’s interior.

The interplay of light and shadow inside attracts photography enthusiasts. Do tread carefully: The floor is littered with brick fragments, there’s some trash, and it can get muddy after rain.

The top of the smokestack (which bears the date “1961”) broke off at some point in the past, and steel buttresses hold up sagging sections of roof. Overall, however, the kiln looks as if it’ll survive for a good while yet.

Despite reinforced concrete now being the preferred construction material, considerable numbers of bricks are still made in Taiwan. In the last decade, annual production averaged more than 700 million. The great majority were fired in electric kilns.

As the government took steps to protect the country’s forests, procuring sufficient wood to fuel Jinshuncheng Bagua Kiln became more difficult. The kiln fired its last bricks sometime in the 1980s — no one seems to know the precise date.

The kiln has been listed as heritage site by Changhua County Government since 2010, yet little has been done to present it as a tourist attraction. The only information board isn’t very legible, let alone informative, even if you can read Chinese. There are no set opening hours, and when I visited it looked as if the surrounding weeds hadn’t been trimmed for a long time.

If you’re seeking a more touristy experience in Huatan, you can also visit Shunda Brick Kiln (順達窯業). Originally a conventional manufacturer of bricks and tiles established in 1965, this business converted itself into a teaching/DIY-art activity facility after the demand for bricks slumped. To find out more, or to contact them before going, visit: www.facebook.com/sdyourbrick/.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

With over 80 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual