Nov. 16 to Nov. 22

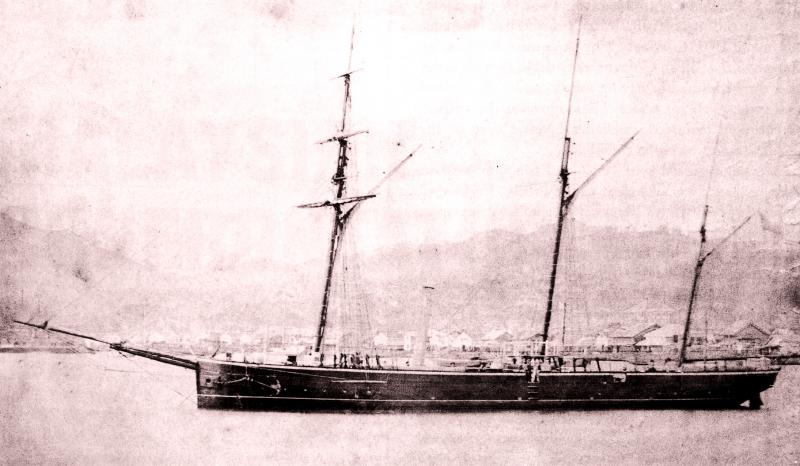

The British gunboats HMS Bustard and HMS Algerine arrived at Anping Port on the morning of Nov. 21, 1868, positioning themselves so the entire area was within firing range.

John Gibson, acting consul on Formosa, and Lieutenant Thornhaugh Philip Gurdon vowed to attack if the British weren’t redressed for the past nine months of grievances under the rule of Taiwan circuit intendant, a position between Governor and Prefect, Liang Yuan-kui (梁元桂). Their primary goal, however, was to coerce the Qing Dynasty government to relinquish control over the lucrative camphor industry and allow for free trade.

Photo courtesy of The British Consulate of Takow

Around 4pm on Nov. 25, the HMS Algerine bombarded Anping with seven massive cannon shots. That night, the British contingent landed and killed 11 Qing soldiers and swiftly occupied the port. The commander, vice-admiral Chiang Kuo-chen (江國珍), committed suicide in shame after the loss, and another six Qing troops died in the final clash. The British suffered no casualties.

The two sides resumed negotiations afterward and signed the “camphor regulations,” where the Qing gave up their monopoly over the trade and agreed to make restitution to the British for previous disputes. Provincial governor Liu Ming-chuan (劉銘傳) would attempt to re-establish the monopoly about two decades later, but that’s a story for another time.

COVETED COMMODITY

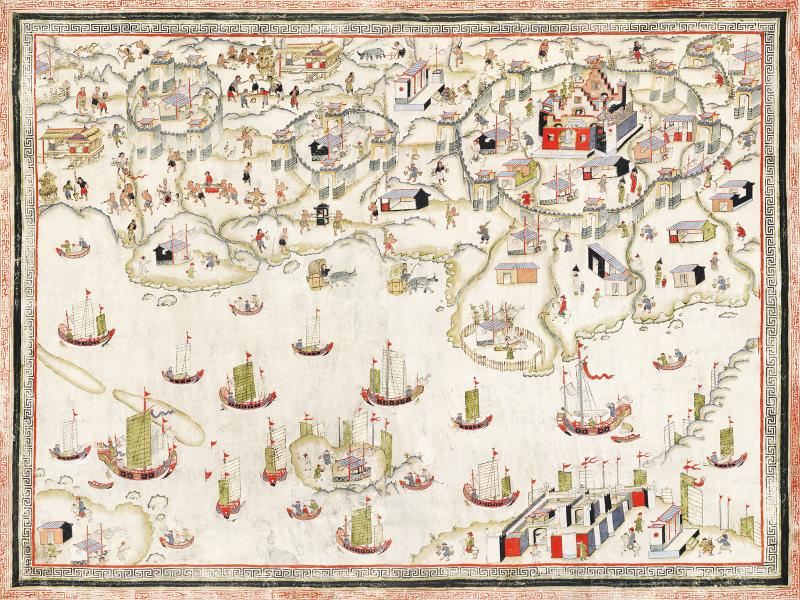

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The ports of Anping and Tamsui were opened up to foreign traders after the Qing Empire signed the Treaty of Tianjin with Russia, the US, the UK and France in June 1858. Takao (today’s Kaohsiung) was also opened in 1864, and the area became a hotbed of activity for foreign traders and missionaries.

At the time, Taiwan’s camphor trade was controlled by the Qing government, as only official warship builders had permission to enter the prohibited Aboriginal areas to obtain timber. As a result, they were the only ones with legal access to camphor, and traded the valuable commodity to fund their operations (and fill their coffers). Of course, illegal private production was also rife.

At the turn of the 19th century, camphor had become one of the empire’s main income sources from Taiwan. China had already depleted much of its own camphor, and Taiwan and Japan were the remaining major producing areas; however records from the 1860s show that Taiwan’s exports far exceeded that of Japan.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

In 1863, the warship timber warehouses were officially converted into camphor producing facilities, with the operations contracted to Han merchants who paid a share to the government. The British saw this as a monopoly that damaged their interests, as they were forced to go through the government to legally trade the product.

In 1867, British representative to Beijing, Rutherford Alcock, lodged a formal complaint to the Qing’s Prince Gong. In addition to blasting the government monopoly as a violation of the trade treaties, Alcock stated that it has also led to rampant illegal trade and armed conflicts between competing merchants.

Chen Te-chih (陳德智) writes in the paper “Tributes and Treaties: Taiwan’s Camphor Dispute as an Example” (羈縻與條約:以臺灣樟腦糾紛為例) that it was a misunderstanding where the British simply wanted free trade of camphor, while the Qing thought that they could reduce the problems by tightening regulations to prevent disputes and illegal behavior, which made the British even angrier. In addition, anti-missionary incidents that year gave the British extra motivation to take action.

Photo courtesy of Rawpixel

SIMMERING TENSIONS

William Pickering left his native England at the age of 16 as a sailor for the British East India Company, arriving in Taiwan in 1863 to work as a customs officer at Takao. In 1868, as Taiwan representative of the British trading firm Messrs Elles & Co, Pickering received orders to “engage in the trade of camphor,” noting in his book, Pioneering in Formosa, that the surging popularity of the product in America had led to a surge in prices and his bosses wanted a piece of the pie.

In February 1868, Pickering made contact with the Tsai (蔡) clan from Wuci (梧棲, location of today’s Port of Taichung), and allegedly with the consul’s approval he acquired a large quantity of camphor and planned to export it directly. But the government caught wind of this, and worked with the local rival Chen (陳) clan to seize the goods.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Pickering personally headed to Wuci, and “with the help of our seven-shooter rifle and two boat guns,” his men and the Tsais drove off the Chens. After two weeks of conflict and negotiation, Pickering appeared to have the upper hand when the consul persuaded him to flee because circuit intendant Liang had put a bounty on Pickering’s head and was planning to kill him.

The case dragged on for months and anti-European sentiment surged. In April, a church in today’s Pingtung County was burned, setting off a series of violent incidents against missionaries and Han converts. And in July, Tait & Co agent J.D. Hardie was stabbed by Qing security guards in a dispute on his way from Takao to Anping.

Relations between the two sides continued to deteriorate, and when talks fell through, acting consul Gibson decided to use military force. The British ended up occupying Anping for two months until the matter was settled.

Although the British finally got their way, Gibson did not benefit from his actions. Pickering writes that the new government in England sent orders to the consulate in Beijing that “in the future, all grievances were to be resolved with diplomacy, and that our vessels of war were not to be used as persuasive methods.” He was removed from his post and died soon afterward.

Things didn’t work out that great for Pickering either. Although he was cleared of his bounty and allowed to legally trade camphor, a bitter Liang tried to sabotage his operations at every opportunity. Frustrated and ill with chronic dysentery, he returned home in August 1870 — but the restless soul soon resumed his adventures in Singapore as its Protector of Chinese.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

The 1990s were a turbulent time for the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) patronage factions. For a look at how they formed, check out the March 2 “Deep Dives.” In the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s the factions amassed fortunes from corruption, access to the levers of local government and prime access to property. They also moved into industries like construction and the gravel business, devastating river ecosystems while the governments they controlled looked the other way. By this period, the factions had largely carved out geographical feifdoms in the local jurisdictions the national KMT restrained them to. For example,

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of

With over 100 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

Ten years ago, English National Ballet (ENB) premiered Akram Khan’s reimagining of Giselle. It quickly became recognized as a 21st-century masterpiece. Next month, local audiences get their chance to experience it when the company embark on a three-week tour of Taiwan. Former ENB artistic director Tamara Rojo, who commissioned the ballet, believes firmly that if ballet is to remain alive, works have to be revisited and made relevant to audiences of today. Even so, Khan was a bold choice of choreographer. While one of Britain’s foremost choreographers, he had never previously tackled a reimagining of a classical ballet, so Giselle was