Today’s ride is a toughie, whichever way you cut it, clockwise or counterclockwise.

More than 130km in length and with six climbs totaling around 3,200m, there’s no beating around the bush, this is going to hurt. Fortunately, a veritable pantheon of deities are in attendance: ru (儒, Confucian), shi (釋, Buddhist) and dao (道, Daoist), as the Chinese have it. And for good measure, you’ll even pass Baptist and Presbyterian seminaries near the end.

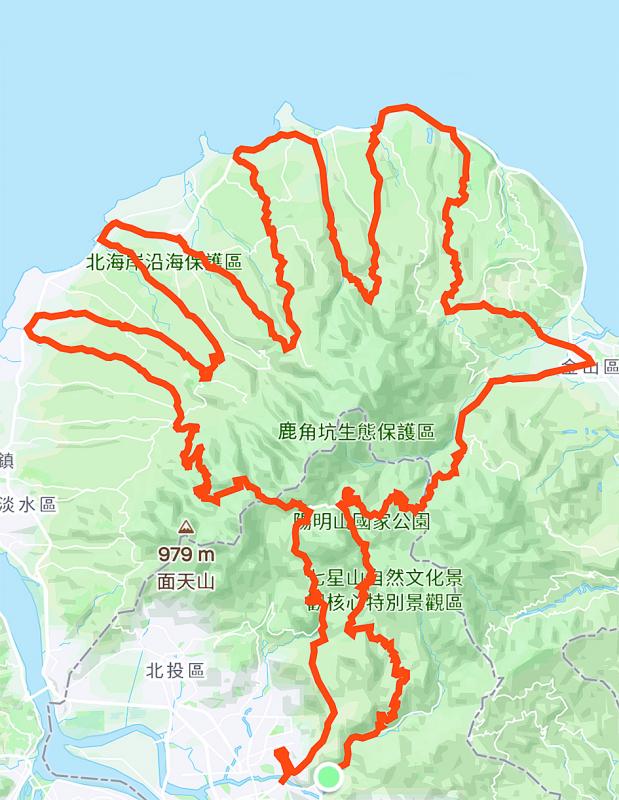

It all started when some wit, who’s name seems forgotten in the mists of two-wheeling history, noticed that, by making multiple ascents into Yangmingshan National Park (陽明山國家公園), you could create a five-fingered hand shape (see map above).

Photo: Mark Caltonhill

He or she baptized this as the Palm of Tathagata (如來神掌) after the 1960s series of Hong Kong martial arts films including The Palm of Tathagata Shatters the Sword Gate (如來神掌怒碎萬劍門; 1965) and The Palm of Tathagata Shows its Power Again (如來神掌再顯神威; 1968).

Tathagata (如來), from the Pali tatha-agata, means something like “one who is thus-come,” that is, someone who, having gone beyond all transitory phenomena, has attained enlightenment. It is how the historical Buddha, Siddhattha Gotama, frequently referred to himself. Maybe completing this ride provides a certain enlightenment.

(There is a more prosaic creation theory: that the route was dreamed up by a convenience store chain’s PR department to get cyclists to visit five of its less-frequented, rural branches.)

Photo: Mark Caltonhill

Enough theory, more practice. You’ll probably want an early start for this one, let’s say 5am or at least 6am, from the “Little 7” (小7; i.e. 7-Eleven) opposite the National Palace Museum in Taipei’s Shilin District (士林區).

Coffeed up, head northeast up Zhishan Road (至善路), then left up its innocuous-enough looking Lane 71 of Section 3. Unless asphalt has been laid recently, a bright yellow hand painted on the road will indicate the way. These should continue for the rest of the way, but downloading a map to your phone is probably recommended too.

Incidentally Zhishan, meaning “supreme good,” comes from the first line of the Confucian text The Great Learning (大學).

Photo: Mark Caltonhill

The lane twists and climbs, takes you through the sleepy village of Pingjing (平菁), which can get a little busy with 4x4s in spring, as families drive up to take selfies against a backdrop of cherry blossom. These date from the park’s original 1937 incarnation as Daiton National Park during the period of Japanese rule.

This was renamed Yangmingshan in 1950 by Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石), when the former Grass Mountain (草山; possibly because grass was all that would grow there after trees were burned down to prevent hiding places for sulfur thieves) was changed to Yangmingshan in honor of Wang Yang-ming (王陽明), 15th-century neo-Confucian philosopher, calligrapher, politician, general and, probably most importantly, fellow native of Chiang’s Zhejiang Province.

Following the golden hands takes you past the International Satellite Communications Center (國際衛星通信中心) with its 30m disc antennae, then up to Lengshueikeng (冷水坑; “Cold Water Hollow”). According to information at the nearby visitor center, this name is due to either hot spring water emerging at “only” 40 degrees Celsius, or that there used to be a cold-water spring here too. Among other interesting and useful information, visitors are also reminded not to tease the cows as they are not pets.

Photo: Mark Caltonhill

After 14km and over 800m of climbing, you can now enjoy a speedy descent to Jinshan (金山; “Gold Mountain”) on Taiwan’s northern coast. Look out for a family of macaque monkeys on the way down; although fairly tame, like the cows, they should not be approached.

Unlike at “Old Gold Mountain” (舊金山), the Chinese name for San Francisco, it is unlikely that gold was ever panned at Jinshan; the name derives from its Ketagalan Aboriginal name, possibly Ki-ppare meaning “bumper harvest” or Kitapari meaning “place where sulfur is collected.” This was transliterated as Kimpauli (金包里), which Japanese administrators shortened to Kanayama (金山) in 1920.

Today’s tourist-targeting Old Street has reverted to using Jinbaoli (金包里). Its bumper harvest is largely of variously colored sweet potatoes but, since these are somewhat impractical for cyclists with over 2000m of climbing still to do, more realistic might be a meal at the Old Street’s duck meat restaurant (金山鴨肉), which draws visitors from afar, while for vegetarians the Dingxiang restaurant (丁香豆花素食水餃) at 159 Zhongshan Road (中山路) has a wide range of options. Hereafter food choices are limited, with the exception of the above-mentioned convenience stores (other brands are available).

Photo: Mark Caltonhill

Leaving Jinshan you will clearly see the headquarters of Dharma Drum Mountain (法鼓山), one of Taiwan’s top-four Buddhist organizations. Despite its avowed intention of blending into the mountainside and eschewing most of the showy aspects of some other monasteries, its ever-expanding size makes it unmissable.

At around 5-6km long and 300m high, each of the next two climbs is relatively straight-forward. A highlight are the two temples dedicated to the Eighteen Princes (十八王公), one of whom is a dog. According to local legend, sometime in the 1860s 17 people plus one dog were shipwrecked nearby. Only the dog survived, but jumped into the grave of its owner to be buried alongside.

Within Daoist traditions, these temples belongs to the yin (陰; shady) division, consequently worshippers tend to be fewer during daytime than after sunset. The dog must have been a smoker, or took the habit up after death, since many visitors place a lit cigarette on its tomb.

Photo: Mark Caltonhill

Zongzi (粽子; rice tamales) are sold outside the second temple; better ones are found 2.5km down the road in central Shimen (石門), named for its natural, wave-created, stone arch.

The fourth climb, being steeper and longer, will bring you back to reality. The fifth is relatively easy again, and the last feels like two: the first section takes you from the coast up 250m to the police station at Beisinjhuang (北新莊), from where it is another 600m climb over 9.5km up Balaka Road (巴拉卡公路) to the Erzihping car park (二子坪).

This, in itself, is a coming-of-age ascent for many in Taipei’s cycling community; today it is just the last of many. And, if you find yourself cycling here after dark, you may find yourself sharing the road with a variety of snakes, some of which may be venomous.

Photo: Mark Caltonhill

This is not the only reason to insist on that 5am departure, however: even more hazardous after dark is riding back down to Shilin among the numerous boy-racers with their souped-up motorbikes and wannabe dragsters. Perhaps better to make that a 4am start.

Mark Caltonhill bikes, and writes, and writes about bikes.

Photo: Mark Caltonhill

This month the government ordered a one-year block of Xiaohongshu (小紅書) or Rednote, a Chinese social media platform with more than 3 million users in Taiwan. The government pointed to widespread fraud activity on the platform, along with cybersecurity failures. Officials said that they had reached out to the company and asked it to change. However, they received no response. The pro-China parties, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), immediately swung into action, denouncing the ban as an attack on free speech. This “free speech” claim was then echoed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC),

Exceptions to the rule are sometimes revealing. For a brief few years, there was an emerging ideological split between the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) that appeared to be pushing the DPP in a direction that would be considered more liberal, and the KMT more conservative. In the previous column, “The KMT-DPP’s bureaucrat-led developmental state” (Dec. 11, page 12), we examined how Taiwan’s democratic system developed, and how both the two main parties largely accepted a similar consensus on how Taiwan should be run domestically and did not split along the left-right lines more familiar in

Specialty sandwiches loaded with the contents of an entire charcuterie board, overflowing with sauces, creams and all manner of creative add-ons, is perhaps one of the biggest global food trends of this year. From London to New York, lines form down the block for mortadella, burrata, pistachio and more stuffed between slices of fresh sourdough, rye or focaccia. To try the trend in Taipei, Munchies Mafia is for sure the spot — could this be the best sandwich in town? Carlos from Spain and Sergio from Mexico opened this spot just seven months ago. The two met working in the

Many people in Taiwan first learned about universal basic income (UBI) — the idea that the government should provide regular, no-strings-attached payments to each citizen — in 2019. While seeking the Democratic nomination for the 2020 US presidential election, Andrew Yang, a politician of Taiwanese descent, said that, if elected, he’d institute a UBI of US$1,000 per month to “get the economic boot off of people’s throats, allowing them to lift their heads up, breathe, and get excited for the future.” His campaign petered out, but the concept of UBI hasn’t gone away. Throughout the industrialized world, there are fears that