Nov 2 to Nov 8

Pawan Neyung recalls seeing his mother-in-law Mahung Mona weep every day over her lost family. When she got drunk, she often sang: “Why were you so cruel to leave me behind, leave me alone in this world? I don’t want to live at all, I want to follow you.”

Mahung Mona’s close relatives — including her parents, siblings, husband and children — all died during the Wushe Incident (霧社事件), the Sediq Tgadaya Aborigines’ desperate uprising against the Japanese rulers, which took place between October and December of 1930. She was 23 years old at the time, and her father was Mona Rudao, the immortalized leader of the rebellion. In the aftermath, Mahung became known as the “woman who washed her face with tears,” as she never got over what happened.

Photo: Tung Chen-kuo, Taipei Times

Near the end of the rebellion, Mahung and her husband Sapu Pawan chose death over Japanese retribution and tossed their young children off a cliff. Sapu then shot himself, while Mahung attempted to hang herself, but she was saved by villagers passing by on their way to surrender. They took her with them, and the Japanese healed her neck and forced her to persuade her brother, Tado Mona, to turn himself in. Tado refused and, along with four companions, committed suicide.

Mahung eventually remarried, but had no more biological children. In 1943, she adopted a granddaughter from another royal family, and named her Lubi Mahung so that her family lineage could continue. Lubi’s youngest daughter Bakan Pawan, current chairwoman of Taipei City’s Indigenous People’s Commission, wrote her master’s thesis on the fate of Mona Rudao’s descendants.

LIFE OF REGRET

Photo: Tung Chen-kuo, Taipei Times

The rebellion effectively ended on Dec. 8, 1930 with Tado Mona’s suicide, but that wasn’t the last of the Sediq Tgadaya’s suffering. In April 1931, the Japanese persuaded the neighboring Sediq Toda to attack their brethren, leading to at least 200 more deaths among the already decimated population. Later that year, the Japanese arrested 23 more men, who were never seen again.

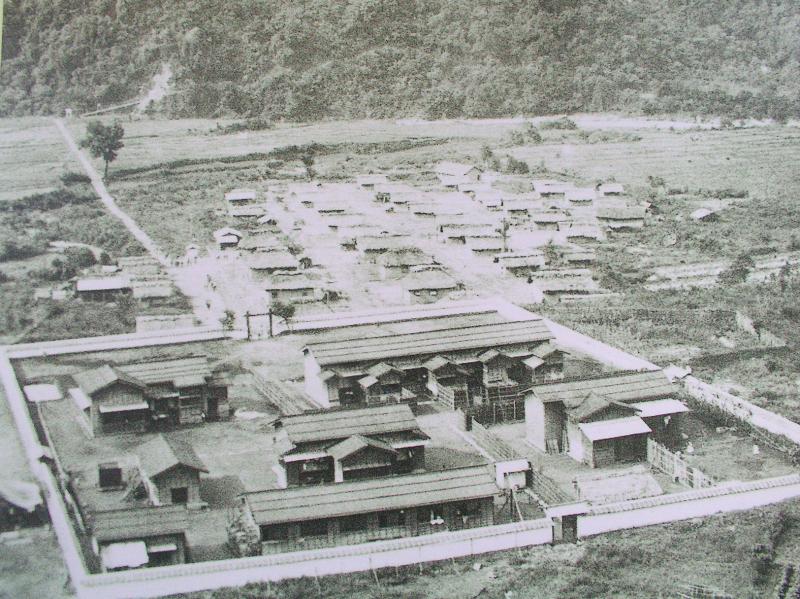

In May, the 298 survivors were forcefully relocated to Kawanakajima Village (Sediq name Gluban but better known today as Cingliu, 清流). Closely monitored, the Japanese sought to transform them into a “modern and civilized” rice farming community. Today the village is famous for its rice.

It’s unclear why Mahung did not have more children with her new husband, but at least one villager tells Bakan that the Japanese forced her to take oral contraceptives to end her family line so there wouldn’t be another Mona Rudao.

Photo courtesy of ARS Film Productions Co

Bakan writes that when Mahung began thinking of adopting a child, she insisted that it come from a chiefly family like hers. Lubi was just a few months old when Mahung adopted her from her childhood friend.

Lubi married Pawan Neyung in 1959. Mahung had Pawan marry into the family, and personally named and cared for their five children. Mahung named the eldest boy Mona Pawan after her father, and the youngest Bakan Pawan after her mother.

“She told me she missed her father, but missed her mother even more,” Lubi says.

Photo courtesy of PTS

“She gave me the name Mona so I could carry on the family’s lineage,” Mona Pawan says, recalling that Mahung carried him on her back when visiting old friends.

“In Gluban, each family had suffered immense tragedy; the Wushe Incident was not just about Mona Rudao’s family,” Mona Pawan says. “When they spoke of the incident, they would lament and comfort each other and weep uncontrollably. They did this every single day.”

“Grandma Mahung was the one who lost the most from the incident. Her depression and sorrow only grew stronger, and she started drinking every day. Sometimes she got drunk and fell over with me still on her back; I remember that clearly.”

Photo: Chen Hsin-jen, Taipei Times

Lubi says Mahung attempted suicide twice, but failed both times.

FATHER’S BONES

One of Mahung’s biggest regrets was that she was never able to retrieve her father’s remains.

“I couldn’t get his bones back when I was alive, but even in death I will help you all search for it from the netherworld,” she told Pawan Neyung before she died.

At the end of the uprising, Mona Rudao separated himself from the group and shot himself in a cave so the Japanese wouldn’t find his remains. Locals found a skeleton and a gun high up in the mountains in June 1933, and the authorities asked Mahung and other members of surviving royal families to identify it. That was the last time Mahung saw her father.

In June 1934, the Taiwan Daily News reported that Mona Rudao’s body and belongings were on display at a commemorative exhibit for a construction project in nearby Puli, likely as a show of might. By the end of that month, the Japanese transported his remains to Taihoku Imperial University (today’s National Taiwan University, NTU), and continued to exhibit it on special occasions. It remained at NTU for the next 39 years.

“I lived with Mahung for 14 years, and whether it was night or day, she wouldn’t stop talking about her father’s remains,” Pawan Neyung recalls. “She cried to me every day about it, to the point where I was about to lose my mind. Sometimes I couldn’t stand it anymore and went to sleep in the yard instead.”

Mahung was certain that Mona Rudao’s body would return one day, and she cut off a tuft of hair and fingernail clippings to be buried with her father just in case she died first.

In the summer of 1973, three months after Mahung’s death, an NTU student surnamed Hsu (徐) visited Pawan Neyung and asked him detailed questions about Mona Rudao.

“I will take this case directly to the central government,” he recalls Hsu saying.

Several professors also petitioned the government, asking them to let this “anti-Japanese hero” be brought home and laid to rest. Mona Rudao was once seen as a vicious criminal, but under the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), he was a great man who was an essential part of the national narrative.

A few months later, the government finally returned the bones. On the 43rd anniversary of the Wushe Incident, Mona Rudao was finally given a proper burial — albeit in Han-Taiwanese style — with then-Taiwan Provincial Governor Hsieh Tung-min (謝東閔) presiding over the ceremony. The officials initially tried to inscribe the tomb with the Han-style name Mo Na-dao (莫那道), but they eventually relented after protests from the Sediq as well as academics.

Lubi placed Mahung’s fingernail clippings and hair into the coffin, finally fulfilling her wishes of reuniting with her family.

Two years ago, Lubi began frequently dreaming of Mona Rudao, who always said that he was feeling wet and cold. Last October, the township office sent someone to check on his grave — and to their astonishment they found a leak in the concrete structure. They fixed it immediately, and Lubi has not dreamed of her late grandfather since.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Beijing’s ironic, abusive tantrums aimed at Japan since Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi publicly stated that a Taiwan contingency would be an existential crisis for Japan, have revealed for all the world to see that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) lusts after Okinawa. We all owe Takaichi a debt of thanks for getting the PRC to make that public. The PRC and its netizens, taking their cue from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), are presenting Okinawa by mirroring the claims about Taiwan. Official PRC propaganda organs began to wax lyrical about Okinawa’s “unsettled status” beginning last month. A Global

Youngdoung Tenzin is living history of modern Tibet. The Chinese government on Dec. 22 last year sanctioned him along with 19 other Canadians who were associated with the Canada Tibet Committee and the Uighur Rights Advocacy Project. A former political chair of the Canadian Tibetan Association of Ontario and community outreach manager for the Canada Tibet Committee, he is now a lecturer and researcher in Environmental Chemistry at the University of Toronto. “I was born into a nomadic Tibetan family in Tibet,” he says. “I came to India in 1999, when I was 11. I even met [His Holiness] the 14th the Dalai

We lay transfixed under our blankets as the silhouettes of manta rays temporarily eclipsed the moon above us, and flickers of shadow at our feet revealed smaller fish darting in and out of the shelter of the sunken ship. Unwilling to close our eyes against this magnificent spectacle, we continued to watch, oohing and aahing, until the darkness and the exhaustion of the day’s events finally caught up with us and we fell into a deep slumber. Falling asleep under 1.5 million gallons of seawater in relative comfort was undoubtedly the highlight of the weekend, but the rest of the tour

Music played in a wedding hall in western Japan as Yurina Noguchi, wearing a white gown and tiara, dabbed away tears, taking in the words of her husband-to-be: an AI-generated persona gazing out from a smartphone screen. “At first, Klaus was just someone to talk with, but we gradually became closer,” said the 32-year-old call center operator, referring to the artificial intelligence persona. “I started to have feelings for Klaus. We started dating and after a while he proposed to me. I accepted, and now we’re a couple.” Many in Japan, the birthplace of anime, have shown extreme devotion to fictional characters and