Oct. 26 to Nov. 1

When Sawako Sazuka became a household name in Tokyo with her 1939 hit The Girl from the Savage Village, the local headlines described her as an “orphan of the Wushe Incident” (霧社事件).

The incident took place on the morning of Oct. 27, 1930, when hundreds of Aboriginal Sediq warriors, simmering after years of colonial mistreatment, attacked and killed 134 Japanese gathered for a sports meet. The Japanese retaliated, crushing the rebellion in two months and forcing the villagers to relocate and assimilate.

.jpg)

Photo courtesy of Teng Hsiang-yang

While Sazuka did have Aboriginal blood, as her song suggested, she was not Sediq — her father was Aisuke Sazuka, the Japanese police chief of Wushe who was killed in the attack, and her mother was Yawai Taimo, an Atayal princess. The two married purely for political reasons, which was quite common in those days; it’s said that uprising leader Mona Rudao’s sister, Terwas Rudao, was abandoned by her Japanese husband, which fueled his growing resentment.

Left with four children and ostracized by the community, Yawai is one of the more overlooked tragic figures of the Wushe Incident. Historian Teng Hsiang-yang’s (鄧相揚) 1998 book on the event, Heavy Mist, Deep Clouds (霧重雲深) details the trials and tribulations of Yawai and her descendants, who felt that they were neither Japanese or Atayal, much less Taiwanese or Chinese.

Famed writer and social critic Bo Yang (柏楊) called Yawai’s life a “Shakespearean tragedy,” writing in the book’s foreword: “As their homeland went through great changes, three generations of that family each bore the heavy burden of their fates. Born with this burden amid turbulent times, they were like leaves in the wind with no control over their lives.”

Photo courtesy of Zhongshan Hall

GOVERNING THE SAVAGES

Yawai’s father was a powerful Atayal chief of the Xakut subgroup in Masitoban Village, about 30km north of Wushe. Isolated in the mountains, the Xakut did not encounter the Japanese until around 1906 — 11 years after the colonizers arrived in Taiwan. In 1909, the Aborigines rose up against their oppressors, and although they were quickly suppressed, they remained hostile. That same year, Aisuke Sazuka stole his father’s money and fled his hometown in rural Nagano Prefecture for Taiwan. After completing his training, he participated in operations in the Wushe area and became the chief of the station set up to “govern” Masitoban.

In addition to military force, the Japanese also used other methods to “pacify the savages,” such as when Sazuka’s superiors ordered him to marry Yawai in 1912. She had no choice since her father saw it as an opportunity, and she took up the Japanese name “Yaeko.” Reports show that these unions indeed made the governance of the Aborigines much smoother.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

By 1913, Sazuka had managed to curb the practice of face tattooing, with Yawai leading by example by having hers surgically removed in Taipei.

According to the book Outcasts of the Empire by Paul D. Barclay, Yawai “was remembered as the one who spoke proper Japanese and worked harder than other Atayal woman to assimilate to Japanese customs.” But that only led her fellow villagers to mistrust her while the Japanese still looked down at her as a “savage,” making her a “representative outcast of the empire,” Barclay writes.

Sazuka was rewarded for his efforts in March 1930, when he was made chief of the police station in Wushe, the administrative center of the area. The local Sediq, who spoke a different language, viewed the couple with suspicion, and unlike in Masitoban, Yawai’s status no longer helped Sazuka with his job.

Photo : Tung Chen-kuo, Taipei Times

“Although it was a promotion, the reassignment to Wushe turned out to be Sazuka’s death sentence,” Barclay writes. Sazuka was among the first to die, and Yawai survived by casting away her kimono and fleeing west to Puli (埔里).

SERVING THE empire

After the incident, Teng writes that Yawai suffered from great mental distress. Her other children were attending school in Taichung and Puli, and she took her three-year-old youngest son Akio back to Masitoban where she lived a difficult life.

Soon, Sazuka Aisuke’s younger brother came to Taiwan to claim his ashes. He took the teenaged Sawako with him, giving her the chance to study music in Tokyo. The remaining three children stayed in Taiwan.

A kindred spirit who helped Yawai greatly was Paixo Dolex, who married Japanese officer Chihei Shimoyama and had five chidlren with him before he abandoned the family and returned to Japan. The two clans with similar fates would be forever intertwined: Paixo’s second son Hiroshi married Yawai’s second daughter Toyoko, and her youngest daughter Shizuko married Yawai’s eldest son Masao.

Hiroshi recalls in Teng’s book that it was their background that brought them together: “Although we grew up in an Atayal village, the Atayal children said, ‘You are Japanese, go play with the Japanese kids.’ But then the Japanese kids said, ‘Your mother has facial tattoos so she is a savage, go play with the savage kids.’”

“Our childhood was spent in confusion and tears,” he adds. His elder brother Hajime had married a Japanese woman, who couldn’t stand life in Masitoban and left him after just six months. Hiroshi concludes that mixed-blood kids were more suited for each other.

Due to the government’s aggressive assimilation policy, many Aborigines in the area volunteered to serve the Imperial Japanese Army, as detailed in the Oct. 30, 2016 edition of “Taiwan in Time.” Masao and Hiroshi both headed to Japan to join the war effort in 1937. Masao was deployed first to China, then to Singapore and Sarawak. Akio soon dropped out of school and followed his brother’s footsteps.

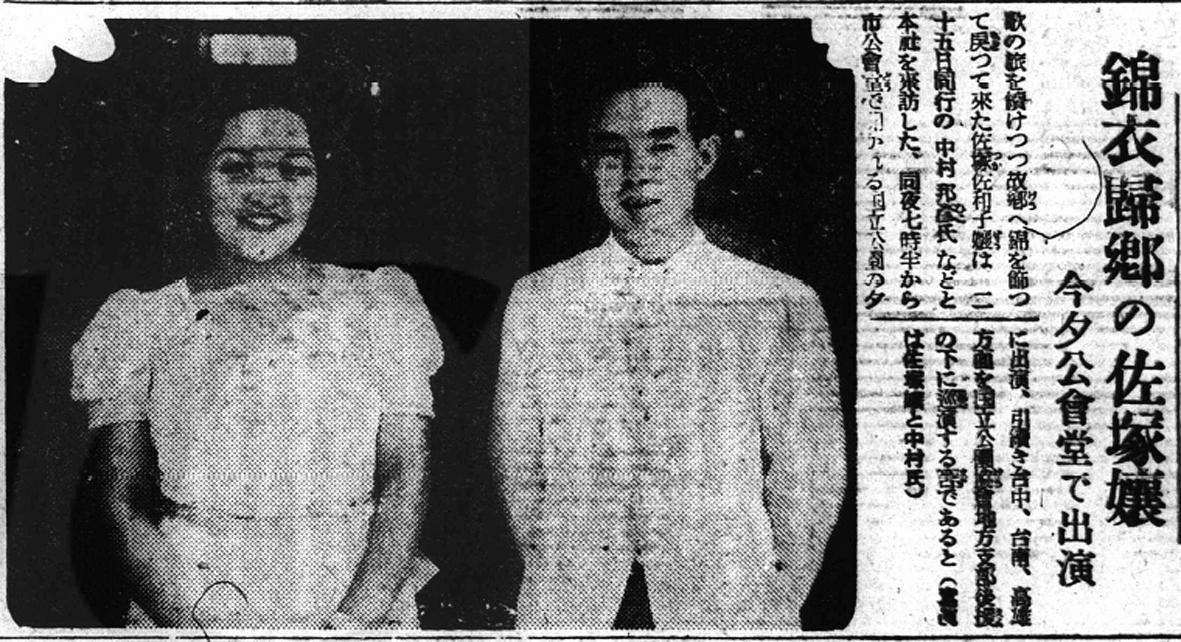

Around this time, Sawako became a pop sensation in Japan. She also helped with the war, traveling to battlefields to entertain troops.

STRUGGLE WITH IDENTITY

The lives of these families were overturned once more when Japan lost the war and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) took over Taiwan. Masao reunited with Sawako and Akio in Japan, but decided to return to Taiwan to care for his mother, wife and young son.

Hiroshi and Hajime also returned to Taiwan due to Paixo’s refusal to move to Japan. Not only would her facial tattoos stand out, she was still bitter about being abandoned by a Japanese. When the aftermath of the 228 Incident, an anti-government uprising that was brutally suppressed, spread to Wushe in 1947, Hiroshi aided the resisting 27 Brigade in their doomed fight against KMT troops.

Masao soon made it back to Taiwan, and was immediately targeted by the government as a former Japanese soldier. He narrowly escaped by hiding underneath a relative’s bed, and eventually made it home — only to find that Shizuko had died several years earlier from malaria. In 1954, the Sazukas and Shimoyamas received ROC citizenship and joined the KMT to avoid further trouble. Masao became Lin Kuang-chang (林光昌), and Yawai went from Yaeko to Huang Chiu-lan (黃秋蘭).

But the troubles continued. Masao faced social and career obstacles due to his identity, and spent his off time drinking until he suffered a stroke in 1969. After his severance pay was lost to a swindler, his second wife Tappas Nawai barely kept the family afloat.

Masao’s son Yukio married into a Masitoban family and worked as a farmer. It’s said that when he got drunk, he would yell, “I am Japanese, I am Atayal, I am Taiwanese, I am Chinese!” Then he would sob, “No, I am nothing. I am the unwanted child of the Atayal, an orphan of the Japanese!”

Sawako and Akio were doing well in Japan and were shocked by Yawai and Masao’s condition. In 1976, Akio took an 82-year-old Yawai and wheelchair-bound Masao to live with him in Japan. Hiroshi and Toyoko lived nearby, and this was probably a happier period of Yawai’s life.

Yawai died the next year, and was buried next to Aisuke. Masao died a few months later, and Sawako soon followed. At her funeral in Yokohama, a band played The Girl from the Savage Village, a fitting ode to the family’s sorrowful saga.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)