OCT. 5 to OCT. 11

After obtaining permission from the Japanese colonizers, the Paiwan Aborigines of Dralegedreg set out for one final hunting trip on the morning of Oct. 9, 1914. Once they caught a “mighty beast,” they promised to surrender their firearms in accordance with the government’s colony-wide policy to “govern the savages” (理蕃).

Around 10am, about 150 Paiwan fighters instead attacked the local police station, killing 11 Japanese officers and members of their families. Only one escaped to report the news to the authorities. Several more Paiwan groups rose up against the colonizers in the following days, with at least three more police stations being attacked. This series of uprisings came to be known as the “Southern Barbarian Incident” (南蕃事件), with fighting continuing until the Japanese crushed the last Paiwan resistance by March of the following year.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

On Oct. 11, the Rukai Aborigines of nearby Vudai (today’s Wutai Township, 霧台, in Pingtung County) also refused to hand over their arms, killing numerous police and torching the local station. Fighting went on for two months before the rebels buckled under heavy cannon fire and massive destruction of their villages.

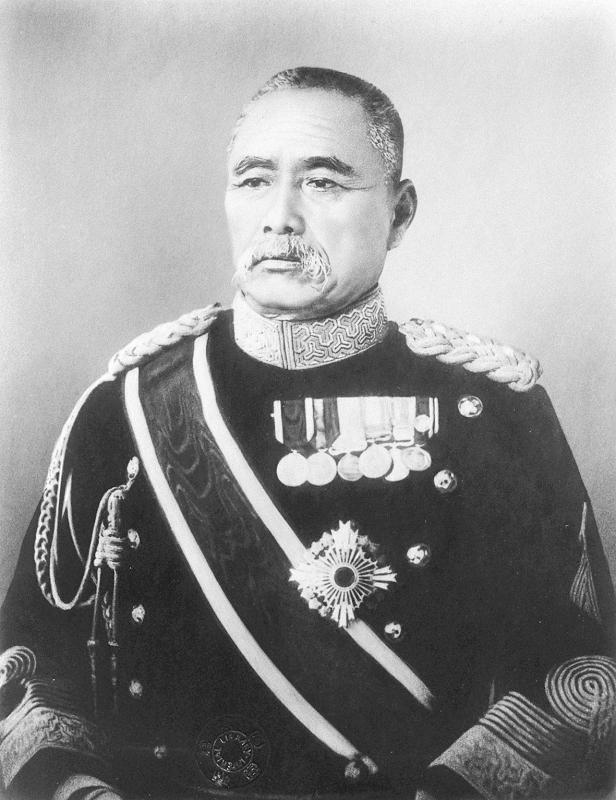

When the Japanese emerged victorious in the Truku War in August 1914, they declared their five-year plan to subdue the Aborigines by force a smashing success. They were confident that the remaining Paiwan, Bunun and Rukai would willingly hand over their firearms. But they were wrong.

The Japanese eventually prevailed, and about 6,000 guns were seized from the Paiwan and Rukai by the end of 1914. Despite scattered resistance, the colonizers by then had the situation under enough control that they shifted gears from military conquest to forced assimilation and collectivization.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“To the Japanese, their five-year plan was a great success, but to the Aborigines, it was nothing but unbearable hardship and sorrow,” writes author Gustave Cheng (鄭順聰) in the book Governing the Savages: 1895-1915 (理蕃政策 : 1895-1915). “The bloody, repressive subjugation of the ‘savages’ allowed the Japanese to finally colonize and economically exploit the Aborigines … The ‘plan’ led to the collapse of Aboriginal society, culture and pride.”

THE FIREARM PROBLEM

As early as 1903, Aborigines who accepted Japanese rule were required to give up their guns.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“The firearms are their only means of acting violently, and we should gradually confiscate them in order to weaken them and stop them from causing trouble,” a police report stated.

Forced confiscation reached its peak in 1914, and by the following year the Japanese had control over most Aboriginal land.

Between 1910 and 1915, a total of 25,700 weapons were taken from Aborigines across Taiwan. A 1921 government report comments on the significance of gun confiscation toward the governing of the Aborigines, noting the difficulty of dealing with “other” ethnic groups by comparing the situation to the Ainu in Japan and the Miao in China.

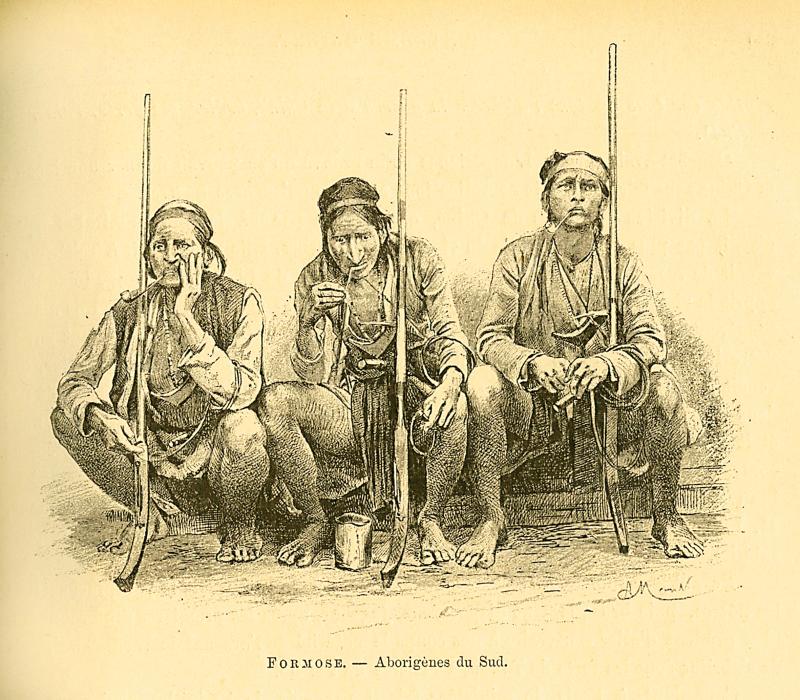

According to “Study of the Southern Barbarian Incident of the Paiwan Tribe During Japanese Colonization” (日本時期排灣族南蕃事件之研究) by Yeh Shen-pao (葉神保), Paiwan Aborigines were already hunting with guns by the mid-17th century, likely obtained from Han migrants.

Although the Qing Empire tried to restrict the importing and manufacturing of guns, possession became increasingly common by the 19th century. The Paiwan also seized firearms during clashes with other groups, and as Qing soldiers fled Taiwan after it was ceded to Japan, the Paiwan scored even more goods by raiding their barracks.

Although guns had only existed in some villages for about 50 years, the Japanese wrote, “The Aborigines see their firearms as extremely important … their attachment toward them is remarkable.”

Like many other Aboriginal groups, firearms became an integral part of Paiwan culture. The weapons served as status symbols, a means to obtain food and played a key role in marriage and religious rituals, Yeh writes. They could also be used as currency to resolve disputes.

In the beginning, the Japanese let the Aborigines keep their weapons as they were busy clearing out Han resistance forces and did not want to cause more discord — although they prohibited the trading of firearms in 1896, a year after they took over rule of Taiwan.

These early efforts were mostly ineffective, as guns continued to flow into Aboriginal areas and were often used in attacks or raids against government or civilian targets. Many villages were heavily armed and remained beyond government control. By 1909, the head of Aboriginal affairs, Rinpei Ootsu, stated, “When gentle methods to restrict and control Aboriginal use of firearms prove ineffective, the only way is to conquer them by force.”

TOTAL DEFEAT

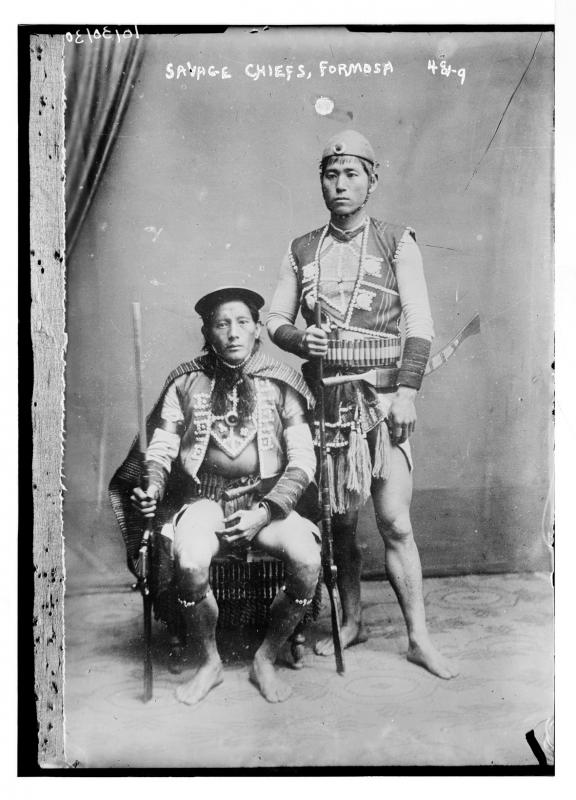

After the Truku War, the Japanese dispatched an expeditionary force comprised mostly of police officers to today’s Pingtung County, hoping to swiftly disarm the remaining Aborigines.

They set out in September 1914, sending out a warning that those who refused would be attacked. Their efforts were successful in most places, but several groups of Paiwan and the Rukai of Vudai decided to make a last stand.

The Japanese captured Vudai in early November, and, after burning the village down, Rukai chiefs began surrendering. By December, they had handed over all of their firearms.

After nine skirmishes over three months, the Paiwan of Dralegedreg had also mostly surrendered, their villages and fields severely damaged by the Japanese.

The Tjakulvulj Paiwan — an alliance of 23 villages — put up the fiercest fight of the incident, using a tactic of feigning to surrender some arms on one day, only to attack again the next day. The Japanese imprisoned the chief to intimidate the warriors, but it only stoked further anger. Over 26 battles, the Japanese attacked with warships, cannons and landmines and burned down entire villages; eventually, on Jan. 2, 1915, the chiefs surrendered one by one and begged for peace.

The last group of Paiwan surrendered in March, drawing the incident to a close. The Japanese then forced them to move to the plains, destroying their social structure and ties to the land.

In Yeh’s study, villagers recall holding a massive ancestral worship ceremony before departing, with all the shamans participating.

“Their calls to our ancestors sounded like demons weeping and spirits howling, fierce and full of anger. The Japanese watched fearfully and carefully, and only then did the villagers depart from the mountains.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

This month the government ordered a one-year block of Xiaohongshu (小紅書) or Rednote, a Chinese social media platform with more than 3 million users in Taiwan. The government pointed to widespread fraud activity on the platform, along with cybersecurity failures. Officials said that they had reached out to the company and asked it to change. However, they received no response. The pro-China parties, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), immediately swung into action, denouncing the ban as an attack on free speech. This “free speech” claim was then echoed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC),

Exceptions to the rule are sometimes revealing. For a brief few years, there was an emerging ideological split between the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) that appeared to be pushing the DPP in a direction that would be considered more liberal, and the KMT more conservative. In the previous column, “The KMT-DPP’s bureaucrat-led developmental state” (Dec. 11, page 12), we examined how Taiwan’s democratic system developed, and how both the two main parties largely accepted a similar consensus on how Taiwan should be run domestically and did not split along the left-right lines more familiar in

Many people in Taiwan first learned about universal basic income (UBI) — the idea that the government should provide regular, no-strings-attached payments to each citizen — in 2019. While seeking the Democratic nomination for the 2020 US presidential election, Andrew Yang, a politician of Taiwanese descent, said that, if elected, he’d institute a UBI of US$1,000 per month to “get the economic boot off of people’s throats, allowing them to lift their heads up, breathe, and get excited for the future.” His campaign petered out, but the concept of UBI hasn’t gone away. Throughout the industrialized world, there are fears that

Most heroes are remembered for the battles they fought. Taiwan’s Black Bat Squadron is remembered for flying into Chinese airspace 838 times between 1953 and 1967, and for the 148 men whose sacrifice bought the intelligence that kept Taiwan secure. Two-thirds of the squadron died carrying out missions most people wouldn’t learn about for another 40 years. The squadron lost 15 aircraft and 148 crew members over those 14 years, making it the deadliest unit in Taiwan’s military history by casualty rate. They flew at night, often at low altitudes, straight into some of the most heavily defended airspace in Asia.