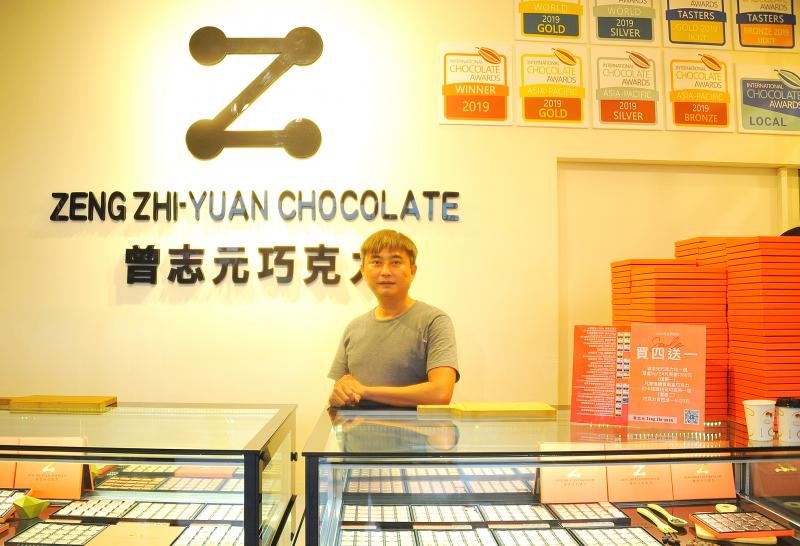

Warren Hsu (許華仁) sees chocolate making as creating art and performing magic. Zeng Zhi-yuan (曾志元) “talks” to his cacao beans and compares the fermenting process to devotedly caring for a child.

Despite their different products and business models, the two helped put Taiwanese chocolate on the map in 2018 at the prestigious International Chocolate Awards’ (ICA) World Finals when Hsu’s Fu Wan Chocolate (福灣) claimed two golds, five silvers and two bronzes, while Zeng took home four golds. That year, Taiwanese chocolatiers burst through the gates with a total of 26 medals, an impressive feat given that many locals don’t even know that the nation produces cacao. The two bagged even more awards at last year’s ceremony. This year’s results will be announced in November.

“I personally believe that my artistic creations are beautiful, flavorful and layered,” Hsu says; some of Fu Wan’s more unusual offerings include zesty white pepper and fleur de sel, as well as sergestid shrimp and almond. “I’m just making something that speaks to me, and I’m fortunate that other people feel the same way too.”

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Virtually all of Taiwan’s cacao is grown in Pingtung County, which now boasts between 200 and 300 hectares of plantations in the heart of betel nut country near the foothills of Dawu Mountain (大武山). When betel nuts started losing value due to their decline in popularity about 10 years ago, some farmers took to growing cacao — an ideal companion crop with betel nut trees because it protects them from the sun — but only in recent years has the chocolate-making side matured.

Unlike their European or US counterparts who import their beans, Taiwan’s chocolatiers employ a tree-to-bar, one-stop-shop system where they either work closely with farmers or grow their own beans. ICA officials noted that Taiwan produces cacao, boasts mature chocolate making abilities and also has a local market with purchasing power, making it unique among cacao-growing nations, most of which are located in Africa and Latin America.

“Taiwan has some of the world’s safest, most convenient and easiest to access cacao farms,” Hsu quips, noting that they can be reached with just a 30 minute car ride after flying into Kaohsiung. While it was just a long and uncomfortable ride to Thailand’s plantations, Hsu says he was robbed when visiting a plantation in Papua New Guinea.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

But unique conditions alone do not win awards. What makes Taiwanese chocolate so special? The Taipei Times visited four chocolate-makers in Pingtung last week to find out.

A TAIWANESE FLAVOR?

The Japanese were the first to plant cacao in Taiwan in the 1930s, but these efforts were discontinued after World War II. There was a brief wave of cacao farming in Pingtung in the 1970s, but it quickly died out because growers lacked the expertise to process the beans.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Around 2002, Chiu Ming-sung (邱銘松), the pioneering “father” of modern Taiwanese chocolate, started growing his crop in Neipu Township (內埔) alongside his betelnut trees with seedlings from Indonesia and Malaysia. Chiu was the first to make his own tree-to-bar chocolate in 2007 through his Choose Chiu’s brand (邱氏咖啡巧克力), years before the Pingtung County Government and other local growers caught on. He estimates that there are over 30 chocolate makers in Pingtung now.

Chiu points to two flavor “miracles” created by the highly hybridized local variants and the area’s microclimate.

“Our cacao beans have a sweet aftertaste,” he says. “They also have a sour quality, and this already defies average cacao stereotypes.”

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Chiu adds that the beans’ low bitterness level has allowed Taiwanese to make 100 percent chocolates that are comparable to 85 percent ones from other countries. But ultimately, he says up to 80 percent of the final product’s flavor profile comes from the fermenting process.

“Each producer has their own methods, but the most important is how attentive you are to the process, adjusting once you feel that something is off,” he says.

Zeng can describe in immense detail the gustatory experience of consuming each of his products, but he finds it hard to come up with a definitive Taiwanese chocolate flavor profile, since fermentation is such a crucial part of the process.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

“Some say that Pingtung cacao beans feature sour, fruity notes with hints of vanilla, but it’s really about how you speak to the beans during fermentation. I can decide what flavor I want, whether it’s nutty or floral tones,” he says.

By “speaking,” Zeng means that he cares for the beans as if they were his own children, remaining attentive and responsive to every little detail and changes that they may exhibit.

Lai Hsi-hsien (賴錫賢), cacao farmer and owner of Wugawan (牛角灣) plantation and chocolate shop, says the low altitude of Taiwan’s plantations gives the beans a gentler, slightly sour taste that is not as overpowering as most foreign varieties.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

“Due to its lighter profile, it’s easy to adjust the flavor while making chocolate,” he says. “It’s why the bean doesn’t stand out, but also why it’s special.”

Hsu also speaks of the evenly-hybridized nature of Taiwan cacao. Major cacao producing countries may specialize in certain strains that yield distinct flavors, but “Taiwan’s cacao beans really don’t have that strong of a character,” he says.

Even so, he can describe clearly the profile of the beans he uses: “There’s an obvious raisin flavor, hints of molasses and rum, some hazelnut, a little bit of licorice, slight aroma of vanilla. On the chocolate flavor chart, it falls right in the middle, bringing a very balanced, clean taste.”

This neutrality also gives Hsu more leeway to tinker through Fuwan’s meticulous fermentation process, where they have identified seven different steps that can each be adjusted for taste. They continue to experiment, and Hsu’s ambition is evident when he talks about creating his own signature fermenting standards: “Maybe one day, Fu Wan and Taiwan’s methods will be used around the world.”

“Fermentation is like performing magic, you can push the flavor in any possible direction,” Hsu adds. “The rest of the world uses more traditional methods, but Taiwan has an advantage in that it already has a solid foundation in food science, microbe science and flavor chemistry. But even if you establish standards, it’s just a framework. In the end, you have to find your own aesthetics and artistic direction.”

While Zeng, Chiu and Lai focus mostly on straight-up dark chocolate, Fuwan boasts a dazzling array of flavors using Taiwanese ingredients such as tea, salt, lychee and shrimp.

“Taiwan has very diverse culinary influences,” he says. “As an island nation, we are good at absorbing foreign influences, which means people are more open-minded towards different flavors and the creativity and imagination that goes into making them. Japan, on the other hand, has a strong artisan spirit, taking a foreign element and excelling at it. In Taiwan, we break it apart and put it back together in our own fusional way.”

CREATING VALUE

Also unique to Taiwanese cacao is how expensive it is — the fruit can go for more than five times the price of major cacao producing countries due to limited production as well as high labor and land costs.

But it’s also led to a situation where producers like Zeng and Hsu can work closely with growers to ensure the quality, quantity and food safety of the beans such as using no pesticides and using organic growing methods. If producers have to make high-end chocolate, then the quality of the cacao fruit is even more important, Zeng says, as he spent years managing and working with farmers on plantations to personally understand the intricacies of growing — again treating the fruit as his children at this stage.

Due to Taiwan’s various past health scares and societal trends toward healthy living, farmers like Chiu and Lai are highly aware of maintaining the health and eco-friendly value of their products. Lai speaks extensively about his commitment to sustainable, natural agriculture, while Chiu insists on additive-free chocolate despite various disadvantages to the final product.

“Adding it would only poison my own people,” he says.

Hsu is willing to work with the farmers’ asking prices, and identify or create value on his end to make the effort profitable. The chocolate has to be more than just a product to justify its prices — the value can be found in social benefits such as revitalizing the area and attracting young people to return home, health benefits by highlighting pesticide-free production, and also through national pride by winning international awards.

“Instead of pushing prices down and exploiting growers, I raise the value of the product. People are willing to pay a little more for sustainability and fair trade ideals too,” he says. He compares it to coffee — consumers are now willing to pay up to NT$200 for a cup of joe because they agree with the product’s spirit, and he hopes to do the same with chocolate.

“Our process is very complex, so if you cannot convince consumers of these prices, then we won’t have the resources to keep improving and experimenting,” he says.

Chiu also hopes to add value to his beans by creating attractive products such as his hot chocolate, which is drank with milk and features a smooth, slightly-sour taste with a sweet aftertaste, although no sugar is added.

But because the industry has taken the high-end route, Chiu says it will collapse if too many people start growing cacao, and he says the scene will have to develop very slowly.

Taiwan also needs to develop a chocolate culture. The nation has a time-honored tea culture with a strict government grading system, as well as a booming coffee shop culture, but “only three out of 10,000 people in Taiwan really understand chocolate,” Chiu estimates.

Chiu is hopeful because Taiwanese are not unfamiliar with chocolate: foreign and local varieties are easily found in all convenience and grocery stores. But factory-made chocolate is different from the high-end, artisan, tree-to-bar products these producers are selling.

“We don’t need to promote the chocolate itself, we just need to tell people that this is from Taiwan, and this are the unique flavors of Taiwan,” he says.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

With over 80 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual