For those who don’t speak Hoklo (better known as Taiwanese), the local forms of glove puppetry and traditional opera are as inaccessible as they are colorful.

Budaixi (布袋戲, “cloth bag drama”) emerged in Fujian Province around 300 years ago, and was carried to Taiwan by Han migrants. Puppet troupes used to earn money by performing at weddings, funerals and temple celebrations, but in the early 1970s, budaixi made the transition to TV. Yunlin-based Pili International Multimedia continues to mass produce episodes that are broadcast on TV, streamed over the Internet and sold in the form of DVDs.

Taiwanese opera, like Beijing opera, is a performing art in which much of the movement is symbolic, rather than realistic. Those watching need to know that striding purposefully in circles means the character is undertaking a long journey; that wringing one’s hands is an expression of anxiety and that bravery is shown by clasping one’s hands behind one’s back. Rather than reproduce the sound of staff clashing against sword, on-stage combat takes the form of acrobatics accompanied by drums and gongs.

Photo: Steven Crook

Museums dedicated to budaixi and Taiwanese opera exist in Yilan City and Chaozhou Township (潮州) in Pingtung County. Both places can claim to be opera heartlands and puppetry strongholds. At both museums, admission is free.

TAIWAN THEATER MUSEUM

Sharing a building with the Cultural Affairs Bureau of Yilan County Government, Taiwan Theater Museum (臺灣戲劇館) has exhibition galleries on three floors coupled with a substantial amount of information in Chinese and English.

Photo: Steven Crook

Yilan is recognized as the birthplace of Taiwanese opera, which has been described as the country’s only indigenous performing art. Retired opera superstar Yang Li-hua (楊麗花) was born in Yuanshan (員山), the town next to Yilan City. The northeastern county also has rich traditions of string puppetry and glove puppetry.

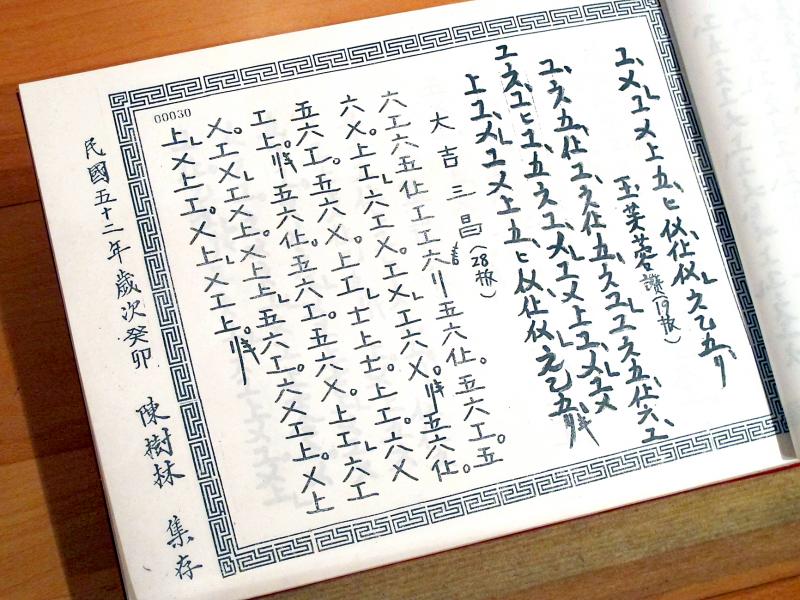

Among the items displayed on the first floor is a book of traditional sheet music, written in a format utterly different to the scores used by today’s trained musicians.

There’s also an explanation of the differences between the beiguan and nanguan forms of opera. Beiguan mostly uses a pentatonic scale, and scores are considered mere outlines which individual musicians elaborate according to their skills and preferences. Nanguan is older, preserving elements from the Tang Dynasty (618 to 907AD). The two traditions use different combinations of musical instruments.

Photo: Chiu Chih-jou

For opera costumes and props, go to the third floor. On weekends, this space is sometimes used by amateur troupes for dress rehearsals. Outsiders are welcome to watch.

The second floor has a beguiling collection of more than 100 string and glove puppets. Some were created for dramas that retell Chinese myths. Others, such as those wearing Taiwanese military uniforms, starred in anti-communist propaganda puppet shows in the 1950s.

Another display on the same floor explains how glove puppets are made. The head is wood, but the face is shaped using resin or clay. The hands, arms, shoulders, and feet are also wood, but glove puppets lack torsos. After clothes have been tailored, the face is painted. If needed, whiskers are glued on. Almost every puppet is given something to hold, such as a sword or a wand.

Photo: Steven Crook

Another location in Yilan often hosting Taiwanese opera performances is the National Center for Traditional Arts (www.ncfta.gov.tw) in Wuchieh (五結) Township.

Directions & Opening Hours

Taiwan Theater Museum is at 101 Fusing Road Sec 2 (復興路二段101號). Walking here from the train or bus stations takes 20 to 25 minutes. The museum is open 9am to midday and 1pm to 5pm from Wednesday to Sunday.

Photo: Steven Crook

MUSEUM OF TRADITIONAL THEATER

Even if you have no interest in performing arts, when passing through Chaojhou you should take a look at the charming redbrick-and-concrete building that houses the Museum of Traditional Theater (屏東戲曲故事館), also known as the Taiwanese Opera & Puppet Museum in Pingtung County.

Built in 1916 by the Japanese colonial authorities, it served as a government bureau and then a telecommunications office. For several years until Typhoon Morakot ravaged southern Taiwan in 2009, it was a post office.

Photo: Steven Crook

While tidying up after the disaster, the beams holding up the tiled roof were found to be riddled with woodworm. A full renovation was ordered, and it was decided to turn the building into a museum celebrating opera and puppetry. It has two smallish galleries, so not much time is needed to see everything inside.

Chaojhou’s connection to the world of Taiwanese opera is through Ming Hwa Yuan Taiwanese Opera Company (明華園), the country’s leading performance group. Founded by a Pingtung native in 1929, the troupe based itself in the town between the early 1960s and its rise to national fame in the 1980s.

Rather than display memorabilia, the museum uses puppets to profile the five character categories in Taiwanese opera (Beijing opera, by contrast, has four). Unfortunately, there’s no English alongside any of the Chinese texts, and the photocopied English-language introduction I was given on arrival wasn’t especially useful.

Photo: Steven Crook

The museum has fewer budaixi puppets than its counterpart in Yilan, but it’s a selection to be savored. I was especially intrigued by a gender-bending brute. Bearded, yet with feminine hands, he didn’t look happy — but neither would I, if my head was on upside-down like his.

Other eye-catching puppets include: a female convict in a cangue; a Western-looking gentleman, said to have been inspired by the Spanish priest who established a church in the nearby town of Wanjin (萬金); and various devils and deities. I now totally understand why some people collect these works of art.

Directions & Opening Hours

The museum, which is open from 9am to 5pm from Tuesday to Sunday, is 1km east of Chaojhou Railway Station at 58 Jianji Road (建基路58號). Parking nearby isn’t difficult.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

With over 80 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual