Aug 31 to Sept 6

A group of “mourners” gathered on Sept. 2, 1989 at the railroad crossing near Taipei’s Zhonghua Road (中華路) to mark the end of an era. They looked left and right repeatedly to confirm that the train really wasn’t coming. From that day on, Taipei’s trains ran underground.

“In the past, these people found it a huge inconvenience to stand there and wait for the trains to pass. But it has become such a part of their life that it now feels odd for the trains to be gone,” reported the Liberty Times (Taipei Times’ sister newspaper). Workers began removing the tracks that day and three months later, no trace was left.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

That same day, the newly opened Taipei Main Station saw over 160,000 visitors passed through it, many just to see the state-of-the-art, Chinese palace-style structure and ride the nation’s first underground railway.

The Liberty Times reported that people were especially impressed with the 526 public phones, “escalators that could be found everywhere, colorful waiting seats, large information screens and air conditioning at just the right comfort level.” Complaints included confusing signage, not enough restrooms and long lines to purchase tickets.

The building is considered the fourth-generation Taipei Railway Station (there was a temporary one that most historians don’t count), and is still in use today. The first generation was a simple steel structure built by the Qing Empire in 1891 upon the completion of the Taipei-Keelung line. Since most goods were transported by water before trains were introduced, this first station was referred to as a “railway wharf.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The station was expanded, demolished and rebuilt several times over the next century, each iteration serving as a major landmark to the nation’s capital.

‘TRENDY ACTIVITY’

Liu Ming-chuan (劉銘傳), the Qing governor of the newly created Taiwan Province, submitted a request to the emperor in 1886 to establish a rail system the following year. In addition to the obvious benefits of transportation, commerce and development, Liu noted that a railroad would make it easier to transport troops in case of a foreign invasion. The French captured Keelung during its war with the Qing in 1884, and defenses were a legitimate concern. Construction began in June 1887.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Entire families traveled from surrounding areas to Taipei in August 1888 to witness the test run of the railroad, which then consisted of one stop between Dadaocheng and Xikou (錫口, near today’s Songshan Train Station). It officially opened to the public on Nov. 16 with two German-made steam engines making four trips per day. At 8-meters long, the passenger cars were very cramped, and people were required to check all their belongings in the cargo car.

Having never been in a vehicle that fast before, many curious passengers just took the train back and forth for fun, making it a “trendy” activity for the first few months.

“Many passengers didn’t even have any business in Xikou; they just rode the train so they could boast to everyone that they had experienced the ultra-fast scientific wonder,” writes Wu Hsiao-hung (吳小虹) in the book, Return to Taipei Station of the Qing Era (重回清代台北車站).

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

There were no proper stations at first, just a “ticketing office” at each stop. The Dadaocheng stop was located not far from today’s Taipei Main Station, just beyond the North Gate (北門, Beimen). These ticketing offices usually consisted of a few traditional red-brick houses, with room for employee dorms and storage; some smaller stops just had a thatched-roof hut. The first “railroad restaurant” was established when the line extended to today’s Sijhih (汐止) area in April 1890.

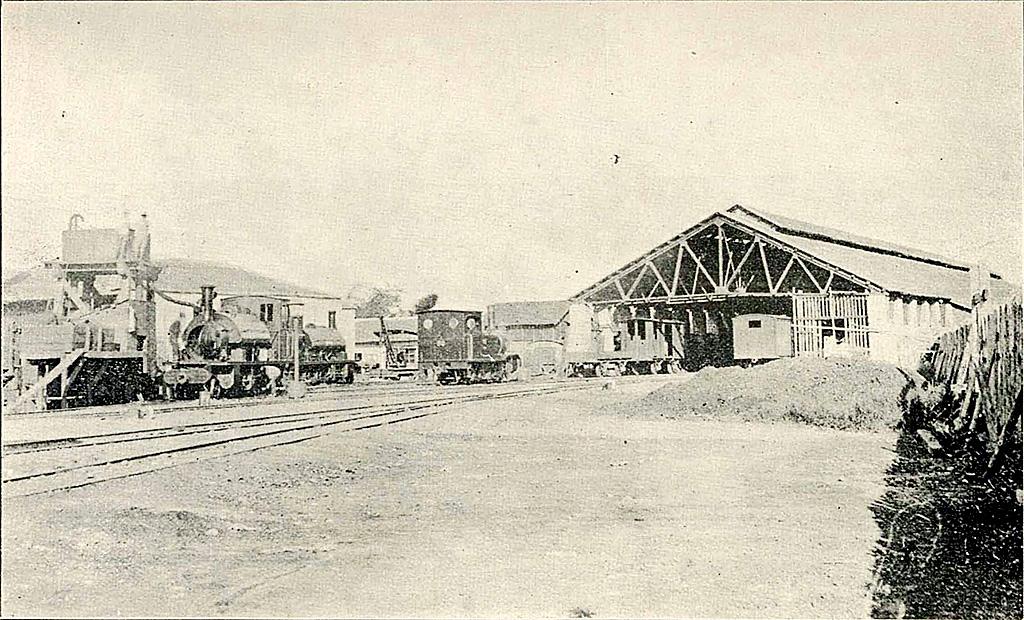

By October 1891, the Taipei-Keelung line was complete. On Oct. 20, the first-generation Taipei “railway wharf” was inaugurated. It was a simple steel frame structure with sloped corrugated roofs that covered the crude “platform.”

By 1893, the line had reached Hsinchu, with nearly 1,000 passengers per day. Qing-era operations were plagued by poor management and corruption, and fare-dodging was rampant. Officials and soldiers rode the train for free under pretenses of official business, and also transported personal goods. The officials did a shabby job at maintaining the equipment, and after five years the railway administration had to cut back the frequency of rides due to engine damage.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

EXPAND AND REBUILD

The Qing ceded Taiwan to Japan in 1895. Taipei Station was reportedly torched during the chaos when the Japanese first occupied the city, but the metal structure survived. The colonizers fixed it up and added a passenger waiting room the following year.

After a massive rerouting project and the opening of the Tamsui line, the Japanese discontinued the original station in 1901, later leasing it to what would become today’s megacorporation Kawasaki Heavy Industries. It was demolished in 1908, and Dadaocheng Station was established in its place. The second-generation Taipei Station was located further east by today’s Zhongshan N Road (中山北路) and featured a renaissance-style red brick building that was much more elegant and imposing than the previous structure. Right outside the entrance was Taiwan’s very first public telephone booth, writes Wu.

The Taiwan Railway Hotel was established across the street in 1908, but it was destroyed by US airstrikes during World War II. Today, the Shin Kong Life Tower sits in its place.

Taipei Rear Station was built from Alishan red cypress in 1923 as the new terminus to the Tamsui Line. During the 1950s, young people moving to Taipei to seek their fortunes exited here, where headhunters greeted them enthusiastically and took them to one of the numerous job placement agencies north of the station. The Tamsui line was terminated in 1988 with the advent of the MRT; the wooden building burned in a fire the following year before any preservation efforts could be made. A small plaza at the intersection of Civic Boulevard (市民大道) and Taiyuan Road (太原路) memorializes this lost structure.

Due to increasing demand, the third-generation, modernist-style building was inaugurated in 1941 with greatly expanded facilities, including a post office, restaurants and lockers.

This station remained in use until February 1986, when the government’s underground railway project warranted a new structure to accommodate the changes. A temporary station was set up next to the construction site — some consider this the fourth-generation Taipei Station and the current one the fifth, but most historians do not count temporary stations. It was torn down in 2000.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.

It’s a bold filmmaking choice to have a countdown clock on the screen for most of your movie. In the best-case scenario for a movie like Mercy, in which a Los Angeles detective has to prove his innocence to an artificial intelligence judge within said time limit, it heightens the tension. Who hasn’t gotten sweaty palms in, say, a Mission: Impossible movie when the bomb is ticking down and Tom Cruise still hasn’t cleared the building? Why not just extend it for the duration? Perhaps in a better movie it might have worked. Sadly in Mercy, it’s an ever-present reminder of just