The final Olympics of the Cold War era took place in what remains as the standoff’s last frontier 32 years later. The two weeks of events during the sweaty summer of 1988 had an impact that reached far beyond sports and influenced the shaping of South Korea as the nation it is today.

Following decades of post-war rebuilding and struggles against military dictatorships, South Korea saw the games as an international coming-out party.

Only the second ever Summer Olympics to be held in Asia after the 1964 Games in Tokyo, more than 8,000 athletes from a then-record 159 countries competed.

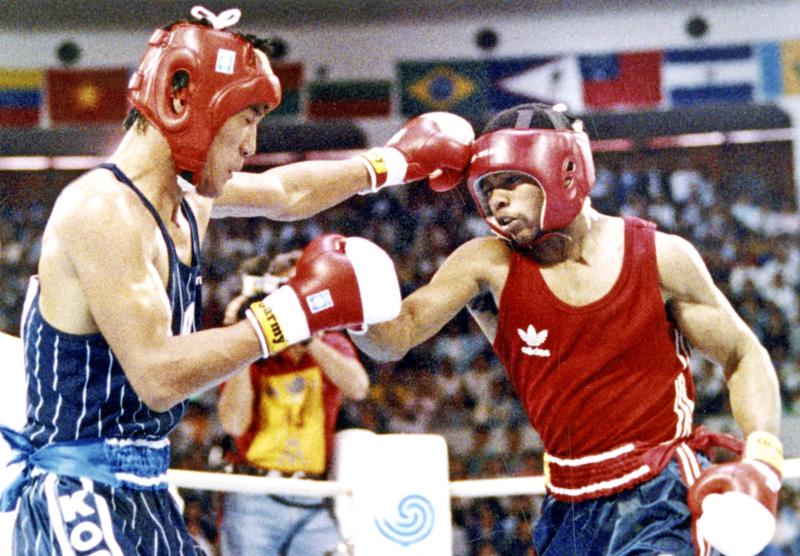

Photo: AP

It became the last Olympics for Communist powerhouses Soviet Union and East Germany, which the South Korean hosts were elated to bring on board after they had boycotted the 1984 Games in Los Angeles.

There was an abundance of star power that generated huge buzz, highlighted by a showdown between Carl Lewis of the US and Ben Johnson of Canada in the men’s 100-meter sprint.

The massive preparations for the Games gave Seoul a dramatic face-lift, with the construction of new roads, bridges and subway lines, the emergence of massive sports complex and huge public parks alongside the Han River, and the remaking of old commercial districts where towering concrete buildings rose above the rubble of old shops and offices.

But the Olympics also had a dark side. The preparations also included ruthless house clearings that removed hundreds of thousands of residents from their homes in slums and low-income settlements, which the country’s military leaders saw as crucial in beautifying the city for foreign visitors.

In a separate attempt to “purify” urban environments of vagrants, the government ordered nationwide police roundups that resulted in thousands — including homeless and disabled people, as well as children — being snatched off the streets and detained at facilities where many were abused.

Army general Chun Doo-hwan’s regime had apparently hoped that staging the Olympics would help legitimize his rule and divert public attention away from his bloody suppression of pro-democracy protests that left hundreds of people dead in the southern city of Gwangju in May 1980. But his government eventually bowed to popular pressure and accepted free presidential elections in the summer of 1987.

The buildup to the Games was also clouded by a belligerent North Korea, which the South blamed for the bombing of a South Korean passenger jet that killed all 115 aboard in December 1987. Seoul saw the attack as an attempt to scare away Olympic athletes and visitors. The North, which at one point demanded to co-host the Olympics, boycotted the Seoul Games.

At the tracks, stadiums and pools, the accomplishments of athletes were often overshadowed by major scandals and controversies.

In the 100-meter final, Johnson beat Lewis comfortably with a world record time of 9.79 seconds, only to have his gold taken away two days later after lab officials revealed he had tested positive for an anabolic steroid. The first Olympic megastar to be disqualified for performance enhancing drugs, Johnson’s case shocked the world and raised public awareness about a growing doping problem in sports.

In boxing, the sport’s future all-time great Roy Jones Jr of the US lost a 3-2 decision to South Korea’s Park Si-hun in the men’s light middleweight final despite clearly out-punching him for three rounds, an outcome that drew jeers even from the South Korean-heavy crowd.

Another boxing controversy involved a bantamweight fight between South Korea’s Byun Jong-il and Bulgaria’s Alexander Hristov. After Hristov was announced the winner, South Korean boxing officials and coaches stormed to the ring and threw punches, kicks and a chair toward referee Kevin Walker of New Zealand, who avoided serious injury but fled the country hours later.

The Soviet Union dominated the medal table with 55 golds, followed by East Germany and the US, which won 37 and 36 golds respectively. The South Koreans came in at a surprising fourth after winning 12 golds.

East German swimmer Kristin Otto led all athletes with six gold medals. American swimmer Matt Biondi won seven medals, including five golds.

South Korea touted the Seoul Olympics as an overall success and continued a shopping spree of mega-sporting events. The country shared the 2002 soccer World Cup with Japan before holding the 2018 Winter Olympics in the sleepy ski resort town of Pyeongchang.

After sitting out the Seoul Games, North Korea sent hundreds of athletes, officials and artists to Pyeongchang, including the powerful sister of leader Kim Jong-un, who conveyed his desires for a summit with South Korean President Moon Jae-in.

The Korean leaders ended up meeting and agreed to send combined teams to the now-delayed Tokyo Summer Games and pursue a joint bid for the 2032 Olympics.

Such commitment now looks all but dead after a quick deterioration in inter-Korean relations amid a stalemate in larger nuclear negotiations between Washington and Pyongyang.

North Korea has severed virtually all cooperation with the South and blew up an inter-Korean liaison office in its territory in June, following months of frustration over Seoul’s unwillingness to defy US-led sanctions over its nuclear weapons program and restart joint economic projects that would help the North’s broken economy.

Dec. 16 to Dec. 22 Growing up in the 1930s, Huang Lin Yu-feng (黃林玉鳳) often used the “fragrance machine” at Ximen Market (西門市場) so that she could go shopping while smelling nice. The contraption, about the size of a photo booth, sprayed perfume for a coin or two and was one of the trendy bazaar’s cutting-edge features. Known today as the Red House (西門紅樓), the market also boasted the coldest fridges, and offered delivery service late into the night during peak summer hours. The most fashionable goods from Japan, Europe and the US were found here, and it buzzed with activity

During the Japanese colonial era, remote mountain villages were almost exclusively populated by indigenous residents. Deep in the mountains of Chiayi County, however, was a settlement of Hakka families who braved the harsh living conditions and relative isolation to eke out a living processing camphor. As the industry declined, the village’s homes and offices were abandoned one by one, leaving us with a glimpse of a lifestyle that no longer exists. Even today, it takes between four and six hours to walk in to Baisyue Village (白雪村), and the village is so far up in the Chiayi mountains that it’s actually

These days, CJ Chen (陳崇仁) can be found driving a taxi in and around Hualien. As a way to earn a living, it’s not his first choice. He’d rather be taking tourists to the region’s attractions, but after a 7.4-magnitude earthquake struck the region on April 3, demand for driver-guides collapsed. In the eight months since the quake, the number of overseas tourists visiting Hualien has declined by “at least 90 percent, because most of them come for Taroko Gorge, not for the east coast or the East Longitudinal Valley,” he says. Chen estimates the drop in domestic sightseers after the

US Indo-Pacific Commander Admiral Samuel Paparo, speaking at the Reagan Defense Forum last week, said the US is confident it can defeat the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in the Pacific, though its advantage is shrinking. Paparo warned that the PRC might launch a “war of necessity” even if it thinks it could not win, a wise observation. As I write, the PRC is carrying out naval and air exercises off its coast that are aimed at Taiwan and other nations threatened by PRC expansionism. A local defense official said that China’s military activity on Monday formed two “walls” east