Aug. 10 to Aug. 16

They called him the “No Problem Doctor” (沒關係醫生) because that’s what he always told his patients when they couldn’t pay up. Operating the only clinic in Changhua County’s Pusin Township (埔心) during the 1950s, Hsu Tsai-chih (許再枝) knew that life was difficult in his remote hometown.

“They barely had enough to survive, so it was pointless to chase after them for the money,” an 81-year-old Hsu told the United Daily News in 2002. “I just went with the flow, some offered to pay me back years later but I had already forgotten about it.”

Photo: Chen Kuan-pei, Taipei Times

Sometimes, patients who received Hsu’s help for free felt too ashamed to go see him again, and their conditions worsened. The affable physician reportedly lost his temper whenever he found out, yelling at the patients for neglecting their health.

Hsu had no intention of retiring at the age of 81, working tirelessly for another 10 years. He received the Medical Dedication Award (醫療奉獻獎) three years later, his acceptance speech consisting of one sentence: “I’m old, I don’t talk much and I’m not good at speaking.” He died in his home on Aug. 12, 2016.

TIRELESS PHYSICIAN

Photo: Chen Kuan-pei, Taipei Times

There are no biographies on Hsu, except for a picture book published by the Pusin Township Office in 2017.

The earliest available article on Hsu ran in the United Daily News in 1999, describing the then-79-year-old as the “only physician in Lotsuo (羅厝) village” who had no intention of retiring.

“Over 50 years, Hsu has treated four generations of the same families, and many old patients refuse to see anybody but him,” the report states. “They pleaded with him to continue practicing, and he is happy to do it too.”

Photo: Chen Kuan-pei, Taipei Times

In response to his children asking him to retire, Hsu said, “It makes me happy to cure other people. It’s my interest and my responsibility. Why can’t they just let me be a happy doctor?”

Hsu was born to a poor farming family in Changhua’s Tianjhong Township (田中). He left home at the age of 14 to train as an intern at his uncle Chen Kun-yuan’s (陳坤源) clinic in Chiayi, staying there for seven years before receiving his license. When he was interviewed in 2014, he was still proud of the fact that he spent six months training at Taihoku Imperial University (today’s National Taiwan University).

He later served as a military doctor for the Japanese in the Philippines during World War II. The details of his service are unclear — one article maintains that he couldn’t stand the discrimination against Taiwanese in the Imperial Japanese Army and eventually deserted, only making it home in 1950. Several other articles state that he served for four years before he was discharged in 1948 — which is unlikely since the Japanese were defeated in 1945.

Photo: Chen Kuan-pei, Taipei Times

Regardless, Hsu re-obtained his medical license under the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in 1952 and opened the only clinic in Pusin Township. Local medical resources were scant in those post-war years, and Hsu saw up to 200 patients a day, doing everything from internal to external medicine to obstetrics — once delivering eight newborns in a night. He often ran into villagers in their 50s or 60s who would exclaim: “You delivered me!”

SAME MEDICAL BOX

Hsu also served the surrounding communities, hopping on his bicycle with his medical box and traveling as far as today’s Yuanlin City, which was over 10km away. He was known for even heading out during typhoons, saying, “the pain of the patients cannot wait.”

Photo: Chen Kuan-pei, Taipei Times

The 1999 article notes that Hsu was still using the same medical box as he did in 1952, and made few upgrades to his clinic, retaining the original wooden signs and furniture. Instead, he donated money to fix local roads and provided the land to build Lotsuo Elementary School.

In 2001, he was nominated for the government’s Medical Dedication Award, and although he didn’t make the final cut, he told the United Daily News, “Just being nominated is an affirmation of my ability ... and it inspires me to continue my dedication toward medical work.”

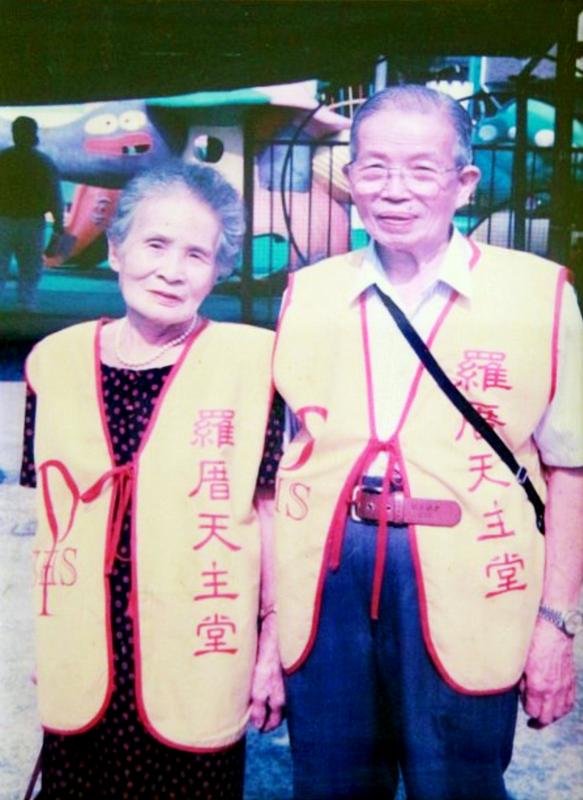

Hsu was a devout Catholic and attended the Lotsuo Catholic Church, which was built in 1880 and is considered the oldest of its kind in central Taiwan. In 1858, the Qing Empire reversed its ban on Catholicism, and missionaries began arriving in the Kaohsiung area soon after, spreading its influence in all directions.

In 1875, a Lotsuo merchant named Tu Hsin (涂心) heard a sermon during a business trip to Kaohsiung and was deeply moved. After he returned home, he gathered family members and prominent locals and invited the church to send a priest to the village. Sixty-three villagers were baptized the following year.

The church has been rebuilt twice and contains many relics, including Taiwan’s first publication using a Latin printing press.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

In late October of 1873 the government of Japan decided against sending a military expedition to Korea to force that nation to open trade relations. Across the government supporters of the expedition resigned immediately. The spectacle of revolt by disaffected samurai began to loom over Japanese politics. In January of 1874 disaffected samurai attacked a senior minister in Tokyo. A month later, a group of pro-Korea expedition and anti-foreign elements from Saga prefecture in Kyushu revolted, driven in part by high food prices stemming from poor harvests. Their leader, according to Edward Drea’s classic Japan’s Imperial Army, was a samurai

Located down a sideroad in old Wanhua District (萬華區), Waley Art (水谷藝術) has an established reputation for curating some of the more provocative indie art exhibitions in Taipei. And this month is no exception. Beyond the innocuous facade of a shophouse, the full three stories of the gallery space (including the basement) have been taken over by photographs, installation videos and abstract images courtesy of two creatives who hail from the opposite ends of the earth, Taiwan’s Hsu Yi-ting (許懿婷) and Germany’s Benjamin Janzen. “In 2019, I had an art residency in Europe,” Hsu says. “I met Benjamin in the lobby

April 22 to April 28 The true identity of the mastermind behind the Demon Gang (魔鬼黨) was undoubtedly on the minds of countless schoolchildren in late 1958. In the days leading up to the big reveal, more than 10,000 guesses were sent to Ta Hwa Publishing Co (大華文化社) for a chance to win prizes. The smash success of the comic series Great Battle Against the Demon Gang (大戰魔鬼黨) came as a surprise to author Yeh Hung-chia (葉宏甲), who had long given up on his dream after being jailed for 10 months in 1947 over political cartoons. Protagonist

A fossil jawbone found by a British girl and her father on a beach in Somerset, England belongs to a gigantic marine reptile dating to 202 million years ago that appears to have been among the largest animals ever on Earth. Researchers said on Wednesday the bone, called a surangular, was from a type of ocean-going reptile called an ichthyosaur. Based on its dimensions compared to the same bone in closely related ichthyosaurs, the researchers estimated that the Triassic Period creature, which they named Ichthyotitan severnensis, was between 22-26 meters long. That would make it perhaps the largest-known marine reptile and would