“For years now, I’ve been saying that I feel like Alice falling down the rabbit hole, with talking cards all over saying off with my head.”

As her life has grown increasingly surreal, the journalist Maria Ressa has gained a newfound sympathy for the dazed girl in Wonderland. In the course of her Zoom interview, she also claims to feel like one of the characters in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, benumbed by a constant stream of media stimulation. She feels like Cassandra as well, doomed to speak truths that fall on deaf ears. And she sometimes feels like Sisyphus, he of the unending boulder-push.

These days, she finds it all too fitting to think of her life in grandly literary or mythological terms.

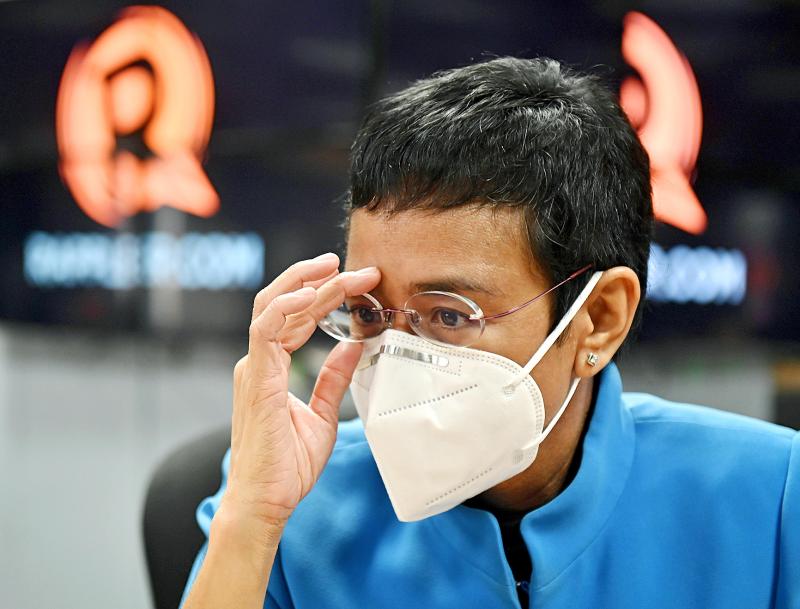

Photo: EPA-EFE

In the time since Rodrigo Duterte was elected president of the Philippines in 2016, Ressa has found herself locked in a good-and-evil struggle of Campbellian proportions. As the co-founder and CEO of the Filipino news outlet Rappler, she’s been one of the major bulwarks against his brutal regime, reporting on the extrajudicial killings and aggressive misinformation campaigns in spite of state-sponsored intimidation to the point of open threats.

Ramona Diaz’s new documentary A Thousand Cuts captures this unfolding conflict as Duterte ramps up his opposition and files cyber-libel charges against Ressa, one in a handful of lawsuits that could place her in prison for up to an entire century. You’d probably start to see yourself as a tragic hero of Grecian legend, too.

As Ressa and Diaz congenially crack each other up via videochat, however, they hardly seem like our final line of defense against the encroaching spread of fascism. The two women share a friendly, warm dynamic that began under more tepid terms back in 2004. Diaz had just completed her debut feature, an Imelda Marcos documentary that led the former first lady and political heavyweight to sue over her depiction.

Diaz’s distributor had set up a handful of interviews while she was in the Philippines defending herself, one of which was with a pre-Rappler Ressa, then the face of CNN in south-east Asia.

“I was like, ‘Oh my God, Maria Ressa wants to talk to me!’” Diaz remembers. “But someone warned me, ‘She actually doesn’t really like the film.’ I said, ‘Then I don’t want to talk to her!’ I wanted to discuss the case, but I didn’t want to litigate my film. I was very tired and beleaguered. Fourteen years later, I’m in her office asking for permission and hoping she doesn’t remember. Of course she remembered. Why she gave me permission is a question for her.”

Ressa’s got an answer locked and loaded.

PERSONAL TOUCH

“If Ramona had denied that moment from 2004 when she came back to meet with me, I don’t think I’d have let her in! That was a good call, confronting it. You passed the test!”

Following what Diaz describes as “a long negotiation,” Ressa allowed the camera crew a rare degree of access to Rappler’s inner operations as well as her own home life. (“Ramona came in, we knew we couldn’t document this ourselves, and I didn’t want to have to pay for it,” Ressa laughs.) For Diaz, gaining entry to Duterte’s inner circle proved much simpler. She received special permissions exceeding those of Filipino press, with approval coming back even before Rappler had gotten on board. Her film spends a goodly amount of time with such tertiary figures as Duterte’s right-hand enforcer Bato and the so-called “queen of fake news” Mocha Uson, both of whom saw their participation as an opportunity to leverage their public profile to their advantage.

“I wanted to have a large ensemble, you know, Robert Altmanesque,” Diaz says. “Getting the participation of Duterte supporters really came down to people always seeing themselves as the hero of their own story. No one sees themselves as a villain. Mocha’s very media-conscious, she understood the power of story. I think they both said yes so they could be part of shaping that story. They think they have the powers of persuasion, that by the end of the process, you’ll see it how they see it.”

DEMOCRATIC BREAKDOWN

Having successfully embedded her production on both sides of the issue, Diaz had a bird’s-eye view of a full-scale democratic breakdown. Her film begins with the savage mass executions perpetrated by Duterte’s officers under the guise of a drug war, and only grows more chilling as he mounts an offensive to justify them.

Ressa stands tall as one of his most vocal critics, her every article incurring harsher recriminations from the government. As she exposes the assorted hypocrisies and cruelties of Duterte’s administration, he constantly defames her as a liar, and that’s one of his less-personal epithets. In one memorable speech, he belittles his enemies by detailing the fullness and frequency of his erections.

Other flashes of the bizarre — Bato karaoke-ing a John Legend ballad, the glammed-up Duterte Dancers performing a Chicago drill routine at one of his rallies — also enliven Diaz’s footage.

“Politics in the Philippines has always been about spectacle,” Diaz says. “It’s entertainment, broken up with a few speeches, and then back to the entertainment. These events are more of a show than a political rally. People show up for the food, and then between the karaoke, it’s Bato talking about how he’s going to kill the drug addicts. So when the day comes that a president talks about his private parts, people can laugh. Imagine me having to translate that to our cinematographers, from the Tagalog. ‘The president says such and such, drug war, corrupt journalists, the usual, and then, oh, he’s talking about his penis.’ They thought I was kidding with them. Even they got used to it, though! That’s the danger, in how quickly this can be normalized.”

To audiences across the west, this narrative will be unsettling in its familiarity. “There are many parallels between Trump, Duterte, Bolsonaro, Orban,” Ressa explains. “It’s a trend that I felt at first in 2014, with the election of Modi in India while I was in Indonesia covering the election of Jokowi [Joko Widodo, the current president]. The world had gotten so complex, that people just wanted to live their lives. They say, ‘Please, someone make these decisions.’ I see this even with my conservative parents in Florida. There’s a yearning for something less complicated. Adding technology to this mix changes what would usually take a course of years and accelerates it. The pendulum swings much faster.”

‘BEHAVIORAL MODIFICATION SYSTEM’

Diaz and Ressa share a focus on the deleterious might of social media, a soapbox that Rappler’s been on since a splashy 2016 piece about the impact of Facebook algorithms on democratic republics.

“The world’ largest distributor of information used to be news organizations. People could debate, take polarized positions, but the facts were never debatable. When you bring in social media — essentially, a behavioral modification system — it put those facts up for debate. Technology has done a lot of damage to democracy,” Ressa says, “and this is why I feel Silicon Valley needs to take responsibility. This can’t be fixed until they do.”

The 24-hour free-for-all of unchecked opinion taking place on Twitter and other platforms has been Duterte’s most effective weapon against anyone standing in his way. His legions of trolls descend on Ressa and Rappler by the thousands, leaving the journalism sector with no choice but to get tough.

“We live on social media, and know it intimately,” Ressa says. “When the hate cranked up, the dehumanization began and targeting of alleged critics came with it. I didn’t really consider myself a critic, and I wouldn’t have been speaking as bluntly as I speak now if my own rights hadn’t been violated. In a way, the Duterte administration forced my growth. I had to define what would be important to me, draw lines that I’d refuse to cross.”

Diaz artfully weaves the global significance of Ressa’s recent tribulations with the interior toll they take on her. We bear witness to extraordinary grace under pressure as she keeps her head up and forges ahead in pursuit of the truth, no matter the cost. Though that could be steep; with seven cases still on her docket, she received a guilty verdict on the first count of cyber-libel , which she’s currently appealing.

“I don’t know where I’m going to end up, and that’s OK,” Ressa says with a shrug. “I’m OK with that. The lawyers say that, cumulatively, all the charges could total 100 years. So yes, it’s real. But at the same time, I know half of it is making myself feel OK with where I am right now. I’m embracing this. The reality of this will be determined by how well I stand by my values now. I can control that, and that’s the reason I don’t doubt.”

She’s less concerned about herself than the good people of Earth.

Whether in the Philippines, the UK or the United States, she’s committed first and foremost to the continuation of free democracy.

Before signing off, she leaves this writer with a chilling warning for the future.

“You’re in New York, right? Your elections are coming up. Good luck.”

On the Chinese Internet, the country’s current predicament — slowing economic growth, a falling birthrate, a meager social safety net, increasing isolation on the world stage — is often expressed through buzzwords. There is tangping, or “lying flat,” a term used to describe the young generation of Chinese who are choosing to chill out rather than hustle in China’s high-pressure economy. There is runxue, or “run philosophy,” which refers to the determination of large numbers of people to emigrate. Recently, “revenge against society” attacks — random incidents of violence that have claimed dozens of lives — have sparked particular concern.

Some people will never forget their first meeting with Hans Breuer, because it occurred late at night on a remote mountain road, when they noticed — to quote one of them — a large German man, “down in a concrete ditch, kicking up leaves and glancing around with a curious intensity.” This writer’s first contact with the Dusseldorf native was entirely conventional, yet it led to a friendly correspondence that lasted until Breuer’s death in Taipei on Dec. 10. I’d been told he’d be an excellent person to talk to for an article I was putting together, so I telephoned him,

From an anonymous office in a New Delhi mall, matrimonial detective Bhavna Paliwal runs the rule over prospective husbands and wives — a booming industry in India, where younger generations are increasingly choosing love matches over arranged marriage. The tradition of partners being carefully selected by the two families remains hugely popular, but in a country where social customs are changing rapidly, more and more couples are making their own matches. So for some families, the first step when young lovers want to get married is not to call a priest or party planner but a sleuth like Paliwal with high-tech spy

With raging waters moving as fast as 3 meters per second, it’s said that the Roaring Gate Channel (吼門水道) evokes the sound of a thousand troop-bound horses galloping. Situated between Penghu’s Xiyu (西嶼) and Baisha (白沙) islands, early inhabitants ranked the channel as the second most perilous waterway in the archipelago; the top was the seas around the shoals to the far north. The Roaring Gate also concealed sunken reefs, and was especially nasty when the northeasterly winds blew during the autumn and winter months. Ships heading to the archipelago’s main settlement of Magong (馬公) had to go around the west side