“Though Chiang was born in Siberia, she displayed the virtues of a traditional Chinese woman,” said then-president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) following the death of Chiang Fang-liang (蔣方良) in 2004. “She was a good mother and a good wife who always put her family first.”

Leaving aside the Confucian morals, there are two striking features about Chen’s statement.

Firstly, Chiang Fang-liang was born about as far from Siberia as possible within the former Russian Empire. The only time she ventured east of the Ural mountains was on a train to Vladisvostok. From there, she proceeded by steamer to Shanghai, never to see Russia again. It was April 1937, a few weeks before her 21st birthday.

This leads to the second point: For the rest of her life, Chiang Fang-liang lived among Chinese and Taiwanese, almost exclusively speaking Mandarin with the thick Ningbo accent she acquired at Xikou (溪口), the ancestral home of Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石). Having wed his son Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國), she was irrevocably committed. The Belarusian Faina Vakhreva had vanished, replaced by the Chinese Chiang Fang-liang.

But Chen could not quite bring himself to call her Chinese. Instead, she merely “displayed the virtues” of a Chinese woman.

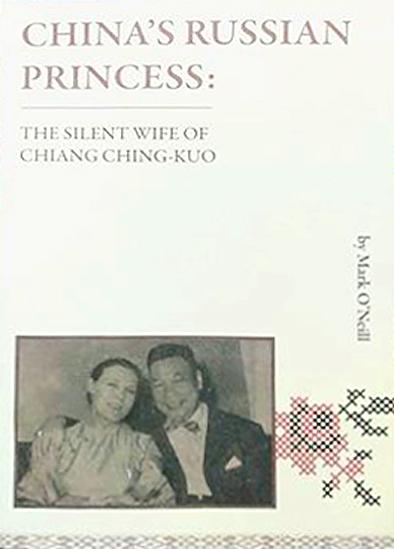

That even Taiwan’s president was clueless about Faina’s background seems surprising. But as Mark O’Neill reveals in China’s Russian Princess: The Silent Wife of Chiang Ching-kuo, Faina was mysterious to all but her family and the select few with whom she associated.

In this first English-language account of Faina’s life, O’Neill, a Hong Kong-based writer, integrates primary sources — interviews with Faina’s daughter-in-law, the owners of Taipei’s “Russian” Cafe Astoria and her notorious youngest son, the late Alex Chiang (蔣孝武) — with Chinese-language biographies and memoirs.

More arbitrary are the conversations with everyday Taiwanese, which O’Neill relays without indicating why they offer insight.

“We know very little about her” says office worker Chang Mei-hwa (張美華) before adding, “She spoke very little — perhaps she was not allowed to speak. She was a simple housewife, with no involvement in politics.”

Taxi drivers are O’Neill’s go-to gauges of public opinion.

Cabbie Huang Li-kuo (黃立國) observes: “Faina has a good reputation among the public,” while fellow driver surnamed Wang says, “The media carried nothing about her. It was martial law. Who dared to ask such questions?”

Contradictions notwithstanding, given Faina’s nebulous existence, these asides are perhaps as illuminating as the biographical claims. In a society where truth was stage-managed and murky, perceptions were everything, the views of the masses represented an alternative reality. At any rate, the published material seems to have lead O’Neill astray.

A photo of a young Faina and Ching-kuo, crouching in the shallows of a body of water is described as having been taken in the mid-1930s at a river near Sverdlovsk (as the Russian city of Yekaterinburg was then known). In fact, it was the Black Sea resort of Sochi in 1935.

O’Neill is not the first person to err here. The best-known biography of Chiang Ching-kuo, The Generalissimo’s Son by Jay Taylor, puts the scene at Crimea. However, Uralmash, the factory in Yekaterinburg where Faina and Ching-kuo worked, has a copy of a postcard from the vacationers to their friends Fyodor Anikeyev and his wife Maria.

With “Sochi Riviera” scribbled in the margin, the note reads “Dear Fedya! We send you heartfelt greetings from Sochi. What’s new with you?” It is signed “Elizarov Kolya [Ching-kuo’s Russian name]” and “Fanya.”

On its own, this is not serious, but it bespeaks a wider problem: O’Neill neither visited Russia, nor contacted anyone there. Had he done so, he might have avoided a significant mistake in claiming Chiang Ching-kuo was under house arrest in 1937, his final year in Russia, after dismissal from his post as editor of the Uralmash newspaper.

“It’s not that simple,” says Sergey Ageyev, senior staff scientist at Uralmash. “Elizarov was defended by the head of the city organization of Communists [Mikhail] Kuznetsov. He was removed from the post of editor, but Kuznetsov immediately provided him with a job in the city council. As for house arrest, this could not be. At that time there was no such measure restricting freedom of persons under investigation. Detainees were held in prisons and shot there.”

While the narrative is generally engaging thanks to the strength of the story, stylistically, things get a little staid, with not much variation in pacing, tone or syntax. Several peculiarities mark the text, too, the use of quotation marks for the word “president” preceding references to Taiwan’s heads of state being notable. One wonders what influenced this decision by the Hong Kong publisher.

Where O’Neill succeeds is in communicating the poignancy of Faina’s lot. He depicts a woman with an “extrovert nature” gradually tamed as her limited pleasures are withdrawn. Games of mahjong are banned, a letter from her beloved sister destroyed, casual outings to markets and cinemas scaled back for security reasons. Gatherings at the Astoria are ruled out due to the cafe’s Russian associations. Gone is the woman who shocked Xikou’s residents by riding horses and donning a swimsuit to bathe in a creek while pregnant.

Her love for her husband permeates each chapter, and they maintained a taboo tactility throughout their half-century of marriage. Still, Faina sacrificed everything to become the dutiful Chinese wife, but — as the Chen quote indicates — was never fully understood or accepted. In the end, her remarkable life was reduced to what she was not. Says Lin Kuo-keung, another of O’Neill’s taxi drivers. “She stayed out of the limelight. She was foreign, not Chinese; she was a housewife, mother and wife.”

Yet, Faina compares favorably to Soong Mei-ling (宋美齡), her predecessor as first lady, who died a year earlier. “She lived simply and was not corrupt,” says cabbie Huang. “After [Chiang Ching-kuo] died, she stayed in Taiwan, which shows she had friends here. As soon as [Chiang Kai-shek] died, his wife went to live in the United States where she had a fortune. Faina did not do that.”

July 1 to July 7 Huang Ching-an (黃慶安) couldn’t help but notice Imelita Masongsong during a company party in the Philippines. With paler skin and more East Asian features, she did not look like the other locals. On top of his job duties, Huang had another mission in the country, given by his mother: to track down his cousin, who was deployed to the Philippines by the Japanese during World War II and never returned. Although it had been more than three decades, the family was still hoping to find him. Perhaps Imelita could provide some clues. Huang never found the cousin;

On Friday last week, China’s state-run Xinhua news agency very excitedly proclaimed “a set of judicial guidelines targeting die-hard ‘Taiwan independence’ separatists” had been issued “as a refinement and supplement to the country’s ‘Anti-Secession’ law” from 2005, with sentencing guidelines that included the death penalty as an option. At the same time, 77 People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) aircraft were flown into Taiwan’s air defense identification zones (ADIZ) in just 48 hours, a high enough number to indicate the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was peeved about something and wanted it known. What was puzzling is that the CCP always

Once again, we are listening to the government talk about bringing in foreign workers to help local manufacturing. Speaking at an investment summit in Washington DC, the Minister of Economic Affairs, J.W. Kuo (郭智輝), said that the nation must attract about 400,000 to 500,000 skilled foreign workers for high end manufacturing by 2040 to offset the falling population. That’s roughly 15 years from now. Using the lower number, Taiwan would have to import over 25,000 foreigners a year for these positions to reach that goal. The government has no idea what this sounds like to outsiders and to foreigners already living here.

David is a psychologist and has been taking part in drug-fueled gay orgies for the past 15 years. “The sex is crazy — utterly unbridled — which of course is partly down to the drugs but also because you can act out all your fantasies,” said the 54-year-old, who has been in a relationship for two years. Chemsex — taking drugs to enhance sexual pleasure and performance — “has opened a whole world of possibilities to me,” David added. “Sex doesn’t have to be limited to two people... There is a whole fantasy and transgressive side to it that turns me on. It