Joe Henley’s heart-rending, emotionally gripping tale of poverty, despair and soul-breaking abuse will haunt the reader long after they put down the book.

While Henley is a Taiwan-based Canadian writer who says he never knew poverty, much less the horrific conditions that migrant workers in Taiwan suffer, he does a convincing job in conveying their suffocating pain, and not given the chance to have any meaningful future.

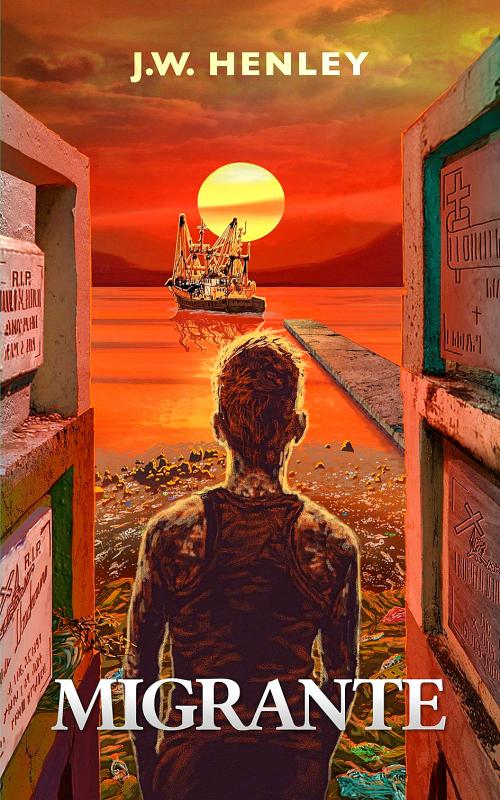

Henley makes it clear in Migrante’s foreword that this is not his story, and that it should ideally be written by one of the workers. But he is certainly qualified to tell the fictional tale of Rizal, an aimless, despondent Filipino youth from the Navota cemetery slums near Manila who ends up working under inhumane conditions on a Taiwanese fishing boat. As a journalist, Henley has spent much time with mistreated migrant workers in Taiwan, as well as residents of the slums in the Philippines, and his experience shows through his vivid descriptions and acute observations.

Turning other people’s true experiences (especially those from completely different cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds) into fiction is not an easy task, which can go awry no matter how well-intentioned the writer is. But Henley pulls it off with great sensitivity and compassion. While migrant worker abuse is being increasingly reported on, there definitely needs to be more substantial ways of getting the story out amidst the constant bombardment of information that turns the world’s tragedies into one big blur.

The annual Taiwan Literature Award for Migrants has been one of the few avenues for these workers to get creative and put a personal touch to these narratives, but unfortunately the anthologies are only available in their native tongues and Chinese.

Last year’s Migrant Workers’ Storybook of Employment Agents by the Migrants Empowerment Network in Taiwan provides a harrowing introduction in English to the issues the abused workers face in their own voices, and Henley’s work provides a much-welcomed addition to this small English-language corpus.

Migrant Workers’ Storybook of Employment Agents packs 15 similar stories into just over 200 pages to show how common the problem is. Migrante, on the other hand, focuses entirely on Rizal’s journey, digging deep into the bleak world he grew up in and the even worse one he enters when a smooth-talking headhunter persuades him to sign a three-year contract — which he can’t read — to head to Taiwan.

Too often these workers are dehumanized as just victims of abuse or illegal runaways, but Rizal, and to a certain extent the people he meets along the way, are shown as full, three-dimensional characters that the reader can identify with. Despite their circumstances, the migrant workers laugh, they banter and they try to make the best of a horrific situation. And even the “bad guys” show their softer sides, making things less clear-cut than one may expect.

As a product of his environment, Rizal is no saint; he’s no hero. He is stuck in the cycle of poverty in the slums of all slums, a place that makes even his fellow Filipino migrantes cringe. With little even menial work available, he spends his days hanging out with his junkie friend and occasionally collecting junk or tending graves for beer money, unable to provide for his estranged infant daughter. But he’s still a likeable guy, and the little hope he still clings on to is what drives him to Taiwan, making him an ideal, sympathetic protagonist for such a tale.

It’s a straightforward story, but the rich descriptions, metaphors and thoughtful prose make it a book hard to put down. The reader is immersed in Rizal’s tribulations, almost able to feel his painful hunger pangs and growing unease as he waits endlessly to be fed after his first night of grueling work on the fishing boat. The fact that his Taiwan experience is worse than his life back home makes the whole experience hurt even more, especially for readers who enjoy a good living here.

The prose is peppered with Tagalog (and sometimes Mandarin) phrases and slang, which further brings the characters to life. The fact that Henley uses mostly slang instead of formal language punctuates his attention to detail, and in one scene he even features a man speaking Tagalog in a distinct southern accent.

This liberal use of language is also the only complaint about Migrante: even though the prose is generally readable without translations of the Tagalog terms, there could have been a glossary or footnotes for those curious about what they mean (this reviewer actually looked up every single word).

Through Rizal’s experiences and his encounters with other migrant workers, Henley manages to cover pretty much all the bases of the mistreatment and exploitation they encounter in Taiwan, from the exorbitant “fees” they are charged to being forced to work without life jackets to direct physical abuse and running away. Since almost all migrant fishers are male, Henley also introduces some female characters to tell their perspective.

It’s not preachy, nor is it told from Henley’s voice as a journalist; the problems are all weaved vividly into the story in mostly meaningful ways. And as a nod to Henley’s other life as a musician, which he chronicles in his previous work Bu San Bu Si: A Taiwan Punk Tale, he also manages to slip a punk element into Migrante through the old school Pinoy band Intoxication of Violence (I.O.V.).

Henley’s goals for this book are clearly stated, as he hopes to help these powerless but “brave, revolutionary spirits” achieve their modest goal of just being treated with decency. In this spirit, all of the book’s proceeds will be donated to migrant worker advocacy groups in Taiwan, who tirelessly lobby the government to fix its policies to little avail.

As Rizal’s experiences are being relived again and again by many of the over 700,000 migrant workers in Taiwan, this is an urgent problem that needs as much advocacy as possible. While it’s unsure how far this book will reach outside of Taiwan’s English-speaking circles, even from a purely literary point of view, it’s still a poignant and compelling read.

Henley will be hosting a book launch party for Migrante on Aug. 22 from 4pm to 11pm at Vinyl Decision, 6, Lane 38, Chungde St, Taipei City (台北市崇德街38巷6號). He will be giving a short talk and reading, while Lennon Wong (汪英達) of Serve the People Association will discuss his work in helping abused migrant workers.

Nov. 11 to Nov. 17 People may call Taipei a “living hell for pedestrians,” but back in the 1960s and 1970s, citizens were even discouraged from crossing major roads on foot. And there weren’t crosswalks or pedestrian signals at busy intersections. A 1978 editorial in the China Times (中國時報) reflected the government’s car-centric attitude: “Pedestrians too often risk their lives to compete with vehicles over road use instead of using an overpass. If they get hit by a car, who can they blame?” Taipei’s car traffic was growing exponentially during the 1960s, and along with it the frequency of accidents. The policy

Hourglass-shaped sex toys casually glide along a conveyor belt through an airy new store in Tokyo, the latest attempt by Japanese manufacturer Tenga to sell adult products without the shame that is often attached. At first glance it’s not even obvious that the sleek, colorful products on display are Japan’s favorite sex toys for men, but the store has drawn a stream of couples and tourists since opening this year. “Its openness surprised me,” said customer Masafumi Kawasaki, 45, “and made me a bit embarrassed that I’d had a ‘naughty’ image” of the company. I might have thought this was some kind

What first caught my eye when I entered the 921 Earthquake Museum was a yellow band running at an angle across the floor toward a pile of exposed soil. This marks the line where, in the early morning hours of Sept. 21, 1999, a massive magnitude 7.3 earthquake raised the earth over two meters along one side of the Chelungpu Fault (車籠埔斷層). The museum’s first gallery, named after this fault, takes visitors on a journey along its length, from the spot right in front of them, where the uplift is visible in the exposed soil, all the way to the farthest

The room glows vibrant pink, the floor flooded with hundreds of tiny pink marbles. As I approach the two chairs and a plush baroque sofa of matching fuchsia, what at first appears to be a scene of domestic bliss reveals itself to be anything but as gnarled metal nails and sharp spikes protrude from the cushions. An eerie cutout of a woman recoils into the armrest. This mixed-media installation captures generations of female anguish in Yun Suknam’s native South Korea, reflecting her observations and lived experience of the subjugated and serviceable housewife. The marbles are the mother’s sweat and tears,