A Sunday afternoon in lockdown and I am standing at the stove watching molten butter burn, because a nice lady in Manchester told me I must and, right now, I’m extremely suggestible. I’ve already had a traumatic interaction with some pastry that was so short it only held together out of good manners. Now here I am, burning butter. I need help. No, what I really need is a restaurant kitchen full of skilled cooks to do this for me, but that’s not exactly available right now.

Do I need tell you that I miss restaurants? I miss their noise and promise and menus and dishwashers. That got me thinking. I can’t bring the restaurant into my home, but perhaps I could bring the food.

Wouldn’t that be great? Pick a few of my favorite dishes and scatter them through my week like suddenly-blooming nasturtium seeds. It would be my food fantasies made flesh, and many other food groups besides.

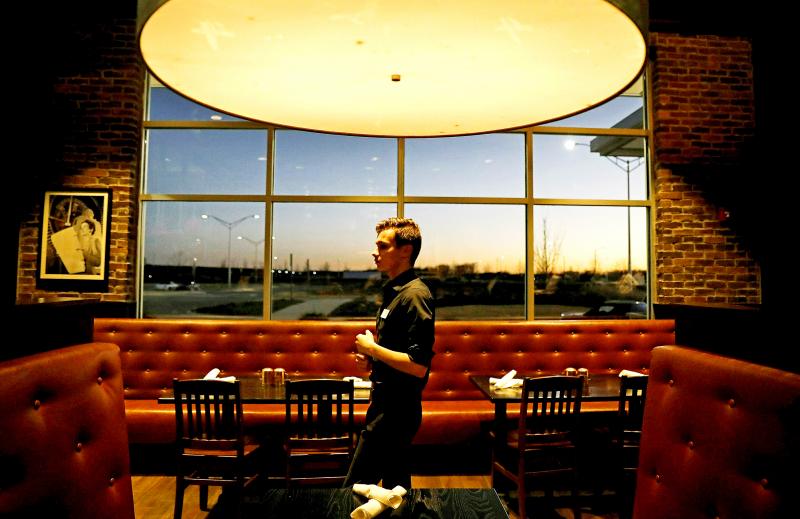

Photo: AP

DUCK, DUCK, DUCK

I start simply with the kind of dish I would once have described pompously, as a “pleasing piece of assembly:” the duck starter served to me at Grazing by Mark Greenaway in Edinburgh. There was a pristine disc of fried duck egg, sunrise-yellow yolk dead center, layered with torn hunks of duck confit, slices of duck ham, fried breadcrumbs and dollops of parsley mayo. Happily, in my south London neighborhood I have shops selling duck eggs, duck confit and flat-leaf parsley. I can’t get duck ham but I can substitute with jamon Iberico.

In lockdown we all must make sacrifices. Oh, the humanity.

Photo: Bloomberg

One lunchtime I attempt to put it together and fall at the first hurdle.

How the hell do you get a perfect disc out of a fried duck egg, let alone secure the yolk in the middle? And yes, I did use a ring. It didn’t work. I whack my deformed egg on to the plate, along with everything else and the Hellmann’s blitzed through with the parsley.

It tasted OK and, compared to a photo of the original, looked fine. Ish.

Photo: Bloomberg

Later, Greenaway sent me his recipes. Bloody hell. It wasn’t that he confited his own duck and cured his own duck ham. I expected that. It was that he whipped up his own mayo with his own parsley oil. The breadcrumbs had 10 ingredients. The only thing he didn’t do was gene splice himself with a duck and lay the bloody egg. As to how he got the frying of that egg so right, he refused to say.

SOUFFLE SUISSESSE

I decided I needed something more challenging, because I am stupid, and don’t know when to quit. The souffle suissesse has been on the menu at Le Gavroche since about 1968. According to Michel Roux Jr, who took over from his father Albert in 1993, it’s been lightened over the years. This is shocking, because, to make four servings, the current recipe (in Le Gavroche Cookbook) calls for six eggs, 600ml of double cream, 500ml of milk, 200g of gruyere, a slab of butter, a defibrillator and a priest standing by to administer last rites.

Michel has recently announced a set of online cooking courses, via video conference, on some French basics. I ask him if he fancies schooling me through this one, via FaceTime. He tells me it’s a tricky dish, but agrees. I have already whipped up the yolk-enriched bachamel by the time we talk. He schools me in the tricky business of folding in the egg whites, while telling me it was the Queen Mother’s favorite dish. No pressure.

I load it into my small buttered tart tins and shove them in the oven, before warming the cream with a handful of the cheese.

“I just saw you lick your fingers,” Michel says to me, cheerily. “I shouldn’t do that, should I?” He shakes his head via the screen of my iPhone. He has grown a magnificent white beard in lockdown, as befits the grandfather he has just become. I am being told off by Santa Claus.

My job is now to turn the set souffle out into a gratin dish filled with the seasoned cream, then layer them with a snowfall of cheese and grill it all again. They should drop into the gratin dish with a pleasing plop. Mine manage more of a resigned slump. I point the phone at the dish. Michel nods.

“It looks, you know, OK.”

We both know it is a recreation of the battle of the Somme in eggs, cream and butter, but fair enough. However, after five minutes under a hot grill it comes out looking like a hot mess.

“Looks all right,” Michel says, which I take as high praise indeed.

Mind you, it’s a delicious hot mess: I cut through the cheesy crust to the soft cloud-like souffle within, the whole lubricated by the thickened cream lake. A thickened cream lake always makes life better. I remind myself that the Queen Mother lived to be 101 on food like this.

After Michel rings off, I summon my family from their lockdown corners and we stand in the kitchen at 11.30 in the morning, spooning away the richest dish ever devised by a nutritionally deviant mind. That evening I do my garden step block workout with more vigor than usual, as an act of penance.

Onwards, to an easy win, mostly because I made up the recipe so there’s nothing to fail against. It’s based on a dish at Baiwei, a Sichuan caff in London’s Chinatown. I braise pork ribs in a broth of soy, sugar and stock for three hours, then press them overnight.

The next day I chop and deep fry them, before seasoning with a mix of cumin, salt, sugar and cayenne. Finally, I dry-fry the ribs with chopped dried red chillies and peanuts. It looks right and tastes right although I am shocked by the sheer volume of seasoning mix it takes to get that full-on, sphincter-burning, jug-of-water-by-the-bed-at-night mouth tingle. It’s a cardiologist’s nightmare.

PIG’S TROTTERS

It’s also a warm-up for dish four: the legendary pig’s trotter stuffed with a chicken mousseline studded with sweetbreads and morels, by the godlike, three-Michelin-star chef Pierre Koffmann. It’s a dish talked about in hushed tones by greedy people. It’s hugely rich and detailed; a gastronomic expression of la France profonde fashioned from more double cream, butter, wild mushrooms, butter, sweetbreads and technique.

It takes me 24 hours to complete.

The recipe in Koffmann’s Memories of Gascony is just a page long, but would be a volume on its own if all the methods required were listed.

For example, it includes items such as “pigs’ back trotters, boned.”

I have to do the boning. It takes hours of squinting at YouTube videos, one hand in an oyster shucker’s gauntlet because I don’t want to visit A&E to explain a self-inflicted haemorrhage: “I was making an essential pied de couchon avec le champignon sauvage when I stabbed myself.”

I’d deserve to bleed to death.

My meaty condom of pig skin must be braised in veal jus, wine and port for three hours. It rests in the fridge, looking like roadkill. The next day I prep sweetbreads from scratch (thank you once more to Michel Roux Jr and Le Gavroche Cookbook). I make a chicken mousseline and? Look, this one has more episodes than Game of Thrones, but concludes with me steaming the finished items. One trotter is a failure. The skin splits. The end dangles off. The mousseline gets waterlogged. But the other one, glazed deep in veal jus, looks just about right. I fork it away, exhausted.

DESSERT

And so to dessert: the wondrous treacle tart served to me by Mary-Ellen McTague at the Creameries in Manchester. She sends me the three-page recipe, which she developed 20 years ago at the Fat Duck with Heston Blumenthal.

There’s that staggeringly butter-rich pastry which refused to be rolled without falling apart. There’s the beurre noisette taken to almost black, then strained through a muslin and then beaten into hot golden syrup to make an emulsion. There’s lemon zest and cream and a lot of washing up. So much washing up.

It would be great for the narrative if I now told you it was a disaster.

It wasn’t. It was a total triumph: thin, crisp pastry, a toffeed surface, a light, citrus-bright filling. I sent a photo to Mary-Ellen.

She replied: “Bloody hell. I’m slightly annoyed.”

She needn’t be. This exercise did not for a moment make me think, “Sod restaurants, I can cook this stuff myself,” even though it turned out that if I concentrated really hard and did literally nothing else with my time for roughly a week, I could. Just about. It made me yearn for restaurants to re-open and do this for me so much better, while I waited at a linen-clad table, basting my companions with rich spoonsful of outrageous anecdote.

This is the year that the demographic crisis will begin to impact people’s lives. This will create pressures on treatment and hiring of foreigners. Regardless of whatever technological breakthroughs happen, the real value will come from digesting and productively applying existing technologies in new and creative ways. INTRODUCING BASIC SERVICES BREAKDOWNS At some point soon, we will begin to witness a breakdown in basic services. Initially, it will be limited and sporadic, but the frequency and newsworthiness of the incidents will only continue to accelerate dramatically in the coming years. Here in central Taiwan, many basic services are severely understaffed, and

Jan. 5 to Jan. 11 Of the more than 3,000km of sugar railway that once criss-crossed central and southern Taiwan, just 16.1km remain in operation today. By the time Dafydd Fell began photographing the network in earnest in 1994, it was already well past its heyday. The system had been significantly cut back, leaving behind abandoned stations, rusting rolling stock and crumbling facilities. This reduction continued during the five years of his documentation, adding urgency to his task. As passenger services had already ceased by then, Fell had to wait for the sugarcane harvest season each year, which typically ran from

It is a soulful folk song, filled with feeling and history: A love-stricken young man tells God about his hopes and dreams of happiness. Generations of Uighurs, the Turkic ethnic minority in China’s Xinjiang region, have played it at parties and weddings. But today, if they download it, play it or share it online, they risk ending up in prison. Besh pede, a popular Uighur folk ballad, is among dozens of Uighur-language songs that have been deemed “problematic” by Xinjiang authorities, according to a recording of a meeting held by police and other local officials in the historic city of Kashgar in

It’s a good thing that 2025 is over. Yes, I fully expect we will look back on the year with nostalgia, once we have experienced this year and 2027. Traditionally at New Years much discourse is devoted to discussing what happened the previous year. Let’s have a look at what didn’t happen. Many bad things did not happen. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) did not attack Taiwan. We didn’t have a massive, destructive earthquake or drought. We didn’t have a major human pandemic. No widespread unemployment or other destructive social events. Nothing serious was done about Taiwan’s swelling birth rate catastrophe.