It’s impossible to write a book entirely in the Taokas language. There are only about 500 recorded words in the indigenous tongue, whose speakers shifted to Taiwanese generations ago while preserving certain Taokas phrases in their speech.

“When I first started recording the language around 1997, I really had to jog the memories of the elders to find anything,” says Liu Chiu-yun (劉秋雲) a member of the Taokas community and a language researcher.

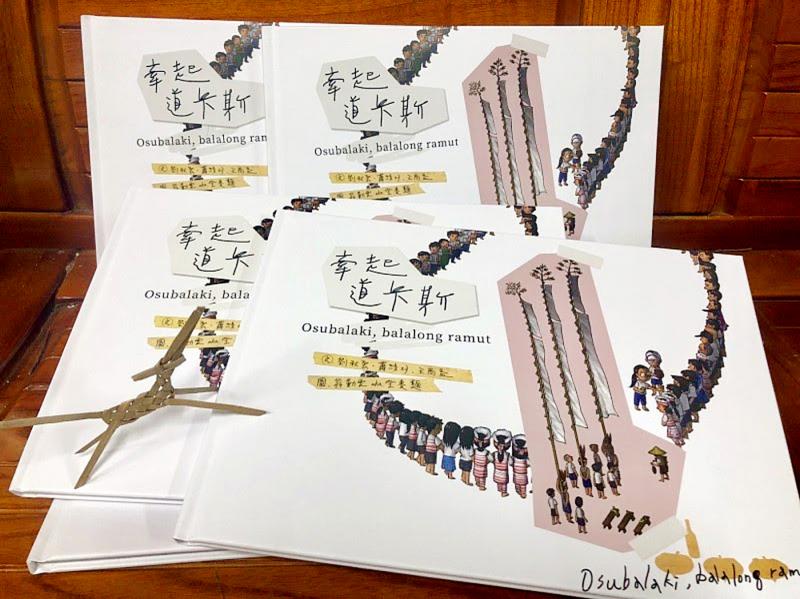

The Taokas last month unveiled a picture book, Osubalaki, Balalong Ramut the community’s first-ever commercial publication using the language. The lavishly illustrated book details their annual kantian festival, which was revived in 2002 after they stopped holding it in 1947 due to cultural suppression.

Photo courtesy of Weng Chin-wen

The main text is in Chinese and English, with Romanized Taokas words and dialogue sprinkled throughout. The book was gifted to all elementary and junior high schools in Miaoli as well as Singang (新港) residents. The Taokas are members of the Pingpu, or plains Aborigines, a community that has yet to be recognized by the government. They reside primarily in Miaoli and Nantou counties.

Kaisanan Ahuan, a Pingpu activist, says that many readers heard of his people for the first time through the book. He only learned that he was Taokas in college and has been studying the language for several years.

“It doesn’t matter if one can only speak simple phrases,” he says. “There’s a prayer during the kantian festival that must be recited in Taokas, otherwise we cannot proceed. It’s very important to us. And if people my age don’t use it, it will disappear.”

Photo courtesy of Weng Chin-wen

CULTURAL RESURRECTION

Kaisanan grew up in Puli Township (埔里) in Nantou County, where a significant number of Taokas migrated in the 1800s from their original homeland along the central coast. Aside from a few Taokas words he heard from elders, he knew nothing about his Taokas roots until he visited Singang in northern Miaoli, where the culture is better preserved.

Liu says the entire village spoke Hoklo when she was little, and although they would sprinkle Taokas into their speech, she didn’t know it was a different language.

Photo courtesy of Weng Chin-wen

“My aunt would say that my son is very obedient during long car rides and doesn’t samali (cry),” Liu says. “I thought that was Hoklo, but she was using Taokas.”

After recording what she could from elders, she began teaching it to whoever wanted to learn. However, because the Taokas have yet to gain official recognition, their language cannot be part of the public school curriculum.

In 2014, the Council of Indigenous Peoples began providing financial support to Pingpu groups to publish books in their own language. At first, the Taokas hung basic vocabulary signs around Singang, and in January last year the Taokas Cultural Association published its first dictionary.

Kaisanan, who heads the Central Taiwan Pingpu Indigenous Groups Youth Alliance, says the existence of Taokas is crucial to gaining recognition.

“Without [our own] language, it’s very hard to convince the government that we’re a separate group,” he says.

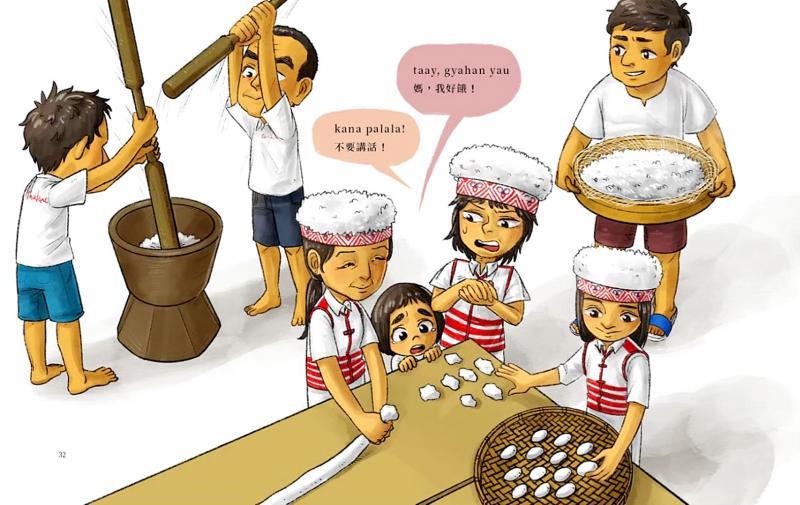

The book is a lively depiction of the preparations for the 2018 kantian festival. The most distinct feature are the male dancers with 30 meter-high bamboo flags tied to their backs. A few elders in the community even remember participating in it as children.

The book contains a photo from the Japanese colonial era of villagers posing with the giant flags. For many, it was the first time they had ever seen an image of the old festival. The authors found the photo in a book by late National Taiwan University anthropologist Hu Chia-yu (胡家瑜).

“Many people were quite moved when they saw the photo,” Liu says. “So the kantian that we heard elders speak of really did happen. Some villagers recognized people in the photo too.”

IMMERSIVE RESEARCH

Kaisanan says the Taokas chose the picture book format because it will appeal to a broader audience. The story revolves around the 2018 festival, so villagers will be familiar with it, as the illustrations accurately depict the real-life participants as well as local scenery.

Liu says that besides kantian, Taokas children have few opportunities or outlets to learn about their ancestral culture.

“It’s another way to preserve our language,” he says.

Before illustrating the book, Weng Chin-wen (翁勤雯) helped with the murals depicting traditional life that adorn the buildings and walls in Singang. She also completed a picture book in 2018 for the Pingpu Kahabu community’s muzaw a azem, a Lunar New Year festival.

For the Taokas project, Weng participated in the kantian festival and interviewed elders. But as a woman, she did not have access to certain preparations and rituals restricted to Taokas men.

Even Liu had never seen the complex process of tying the flagpoles to the dancers’ backs until she asked her cousin to film it for Weng last year. Using the footage, Weng repeatedly revised her illustrations until the elders deemed them accurate.

Kaisanan and Liu say they want to create more educational material in the future, partially to help their efforts to win government recognition.

“We hope that the government sees that we do have the resources and materials to teach [Taokas],” Kaisanan says.

Liu says she is happy about the “small progress” the community has made preserving Taokas over the past two decades, but she also worries about its future.

“Our population is small, and it’s not a language that can be used daily. The practical applications are very limited,” she says. “But we have to do what we can.”

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she