June 15 to June 21

The slogan “One [child] is never too little, two [children] is just enough” (一個不嫌少,兩個恰恰好) was devised in 1971 to urge people to have fewer kids, a stark contrast to the government’s efforts to drive up the birthrate today.

Socioeconomic changes caused the birthrate to drop below targeted levels in the mid-1980s, and the department of health (today’s Ministry of Health and Welfare) in 1996 revised the slogan to: “Two [children] are just enough, three [children] are never too plenty” (兩個恰恰好,三個不嫌多).

Photo courtesy of Amigororo

It hasn’t worked. Ministry of Interior statistics released last week show that Taiwan is on track to experience negative population growth for the first time this year, and the population is estimated to drop to 20 million by 2050.

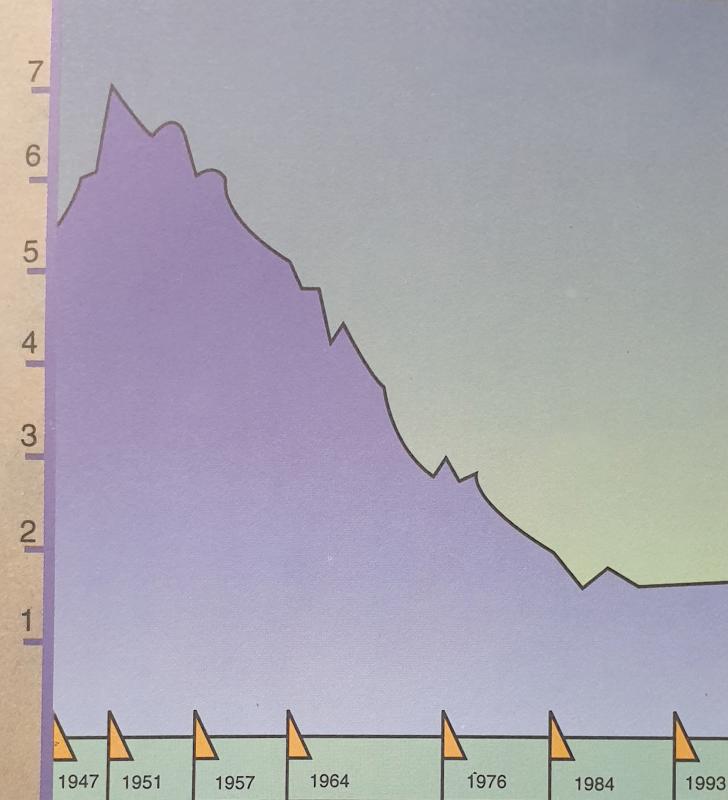

The nation experienced a population boom during the early days of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) rule following World War II. In addition to the influx of refugees, soldiers and government officials from China, people were encouraged to have more children to support the war effort against the Chinese Communist Party.

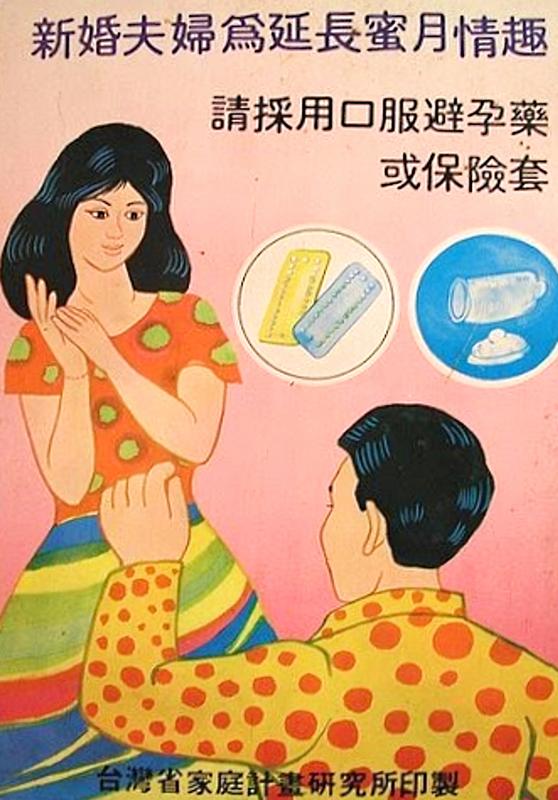

But with concerns about overpopulation growing among officials, the government implemented a series of family planning and birth control policies in the 1960s. Having no more than two children and not discriminating between boys or girls was the centerpiece of the campaign, with the slogans remaining familiar catchphrases for most Taiwanese.

Photo courtesy of Amigororo

A TABOO SUBJECT

The nation’s birth control efforts were so successful that the US-based Population Action International ranked it first in 1987, 1992 and 1997 among 95 developing countries for family planning.

But in the beginning, it wasn’t so easy to convince the government. Chang Ming-cheng (張明正), who spearheaded the now defunct Taiwan Provincial Institute of Family Planning, recalls: “Not only was there no policy or law to support birth control, government, military, academic and religious leaders were all against it. The myriad reasons included contradicting [KMT founder] Sun Yat-sen’s (孫逸仙) teachings, affecting the source of troops and opposing traditional ethics and morals.”

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Family Planning Institute

In Chinese culture, it was a virtue to have many descendants.

Sino-US Joint Commission on Rural Reconstruction chairman Chiang Meng-ling (蔣夢麟) was the first official to openly support birth control, although with US support civic groups had been offering limited family planning in rural villages since 1954.

When the commission was established in Taiwan in 1949, its members, including Chiang, were in favor of boosting agricultural production to deal with the population increase. As long as they used scientific methods and industrialization to upgrade the industry, Taiwan would be fine for the next 30 years, Chiang wrote in 1953.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

As a result, Taiwan averaged 6.3 births per woman between 1951 and 1961. Chiang changed his mind after taking a tour of rural Taiwan and seeing people living in overcrowded, squalid households with a high child mortality rate. US representatives from the commission also noted that Taiwan couldn’t sustain its population growth rate, but most Taiwanese officials remain unconvinced.

By August 1958, then-provincial governor Chou Chih-jou (周至柔) showed signs of relenting: “From a government standpoint, we will not promote birth control. But from the people’s point of view, whether for economic or other reasons, we will not prohibit birth control either.”

In 1959, Chiang held a press conference to present his paper, “Let us face the increasingly urgent population problem of Taiwan,” (讓我們面對日益迫切的台灣人口問題), urging the government to focus on the quality instead of quantity of the population, and warning that rampant development and growth will upset the balance of the environment and deplete natural resources.

Photo courtesy of Chunghwa Post

One of Chiang’s main opponents was the Catholic Church, which, in addition to religious reasons, cited the teachings of Sun Yat-sen, a staunch proponent of population growth to strengthen the nation. This belief was later called into question when Sun’s son, Sun Fo (孫科) assured fellow officials that birth control did not contradict his father’s ideals.

An adamant Chiang proclaimed that he would “advocate for birth control even if I lose his head.”

The first government-sponsored family planning initiative was launched in 1961 in Nantou County, but it was called “pre-pregnancy health” to avoid contradicting the government’s stance. It targeted women who had four or more children and encouraged them to use contraception. It also urged them to wait between pregnancies.

The program soon expanded to other counties. Meanwhile, concerns over the post-World War II population explosion grew in the West. With support from the Rockefeller Foundation’s Population Council, the Taiwan Population Study Center was established in September 1961. It introduced to Taiwan the Lippes Loop and other intrauterine contraceptive devices. Until the government included the condom in its recommended methods in 1970, birth control was mainly targeted toward women.

In 1964, the government announced its support for birth control and launched the first nationwide family planning program.

‘3-3-3-3-3’ GUIDELINES

The 1967 “3-3-3-3-3” guidelines were widely disseminated through the media: wait three years after marriage to have children, allow three years between each pregnancy, refrain from having more than three children and stop giving birth after the age of 33.

In 1971, the guidelines were changed to emphasize having no more than two children, and that boys and girls are equally favorable. Between 1961 and 1981, the nation’s fertility rate fell from 5.59 births per woman to 2.46.

Despite the success, the government took on a more urgent tone regarding the two-child recommendation in the early 1980s due to changes in society.

“This is not an idealistic slogan, it’s an urgent need,” a pamphlet from 1984 states. Overpopulation had led to fierce competition, which meant exponentially higher child-rearing costs as parental expectations rose.

“Traditionally, as long as the parents provide for their basic needs, their children will ‘naturally’ mature. That does not fit today’s society anymore … in addition, ‘sacrificing everything for one’s children’ is an outdated concept as parents should also be able to enjoy a quality life.”

By 1986, the total fertility rate had dropped to 1.68 births per woman — dipping below the two-child recommendation. And it would continue to fall. In the late 1990s, the government started worrying about the prospects of an aging society. They began urging people to have three children again — but nothing could reverse the tide, resulting in today’s predicament.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

March 24 to March 30 When Yang Bing-yi (楊秉彝) needed a name for his new cooking oil shop in 1958, he first thought of honoring his previous employer, Heng Tai Fung (恆泰豐). The owner, Wang Yi-fu (王伊夫), had taken care of him over the previous 10 years, shortly after the native of Shanxi Province arrived in Taiwan in 1948 as a penniless 21 year old. His oil supplier was called Din Mei (鼎美), so he simply combined the names. Over the next decade, Yang and his wife Lai Pen-mei (賴盆妹) built up a booming business delivering oil to shops and

The Taipei Times last week reported that the Control Yuan said it had been “left with no choice” but to ask the Constitutional Court to rule on the constitutionality of the central government budget, which left it without a budget. Lost in the outrage over the cuts to defense and to the Constitutional Court were the cuts to the Control Yuan, whose operating budget was slashed by 96 percent. It is unable even to pay its utility bills, and in the press conference it convened on the issue, said that its department directors were paying out of pocket for gasoline

On March 13 President William Lai (賴清德) gave a national security speech noting the 20th year since the passing of China’s Anti-Secession Law (反分裂國家法) in March 2005 that laid the legal groundwork for an invasion of Taiwan. That law, and other subsequent ones, are merely political theater created by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to have something to point to so they can claim “we have to do it, it is the law.” The president’s speech was somber and said: “By its actions, China already satisfies the definition of a ‘foreign hostile force’ as provided in the Anti-Infiltration Act, which unlike

Mirror mirror on the wall, what’s the fairest Disney live-action remake of them all? Wait, mirror. Hold on a second. Maybe choosing from the likes of Alice in Wonderland (2010), Mulan (2020) and The Lion King (2019) isn’t such a good idea. Mirror, on second thought, what’s on Netflix? Even the most devoted fans would have to acknowledge that these have not been the most illustrious illustrations of Disney magic. At their best (Pete’s Dragon? Cinderella?) they breathe life into old classics that could use a little updating. At their worst, well, blue Will Smith. Given the rapacious rate of remakes in modern