Over the past few years, I’ve grown to really appreciate Liouguei District (六龜). It’s one of the most scenic and thinly populated parts of Kaohsiung.

The number of humans living here has steadily declined since the 1980s. With barely 12,500 adults and children spread over 194 square kilometers, Liouguei’s residents enjoy more space per person than folks in Hualien County.

Liouguei is dominated by the Laonong River (荖濃溪), a major tributary of the Kaoping River (高屏溪). Within the district, there are four river crossings. Three are part of the provincial highway network; the fourth belongs to Kaohsiung Local Road 131.

Photo: Steven Crook

Following up on a brief visit a few weeks earlier, I recently drove along Provincial Highway 20 into the northern part of the district, then turned south onto Provincial Highway 27. I found the turnoff and bridge for Local Road 131 about 6km from the intersection of highways 20 and 27.

On the western side of the Laonong River, the road worked its way through a small village before entering a tract of beautiful back country. This, I’d learned from a road sign on my previous visit, is the Colorful Butterfly Valley Scenic Area (彩蝶谷風景特定區).

The scenic area comprises 485 hilly hectares of brushy woodland dotted with stands of teak and kassod. It’s not a single valley, but rather eleven interconnected drainages. Several of the streams dry up during the cool season, but there’s usually water in the Hongshuei Creek (紅水溪) and the Jhujiao Creek (竹腳溪).

Photo: Steven Crook

More than 250 butterfly species have been recorded here, and it’s said that pretty much anytime between March and October you can expect to see a good number and variety of lepidopterans. From what I saw, I wouldn’t consider it much of a butterfly hotspot, certainly when compared to the Purple Butterfly Valley (紫蝶幽谷) in Maolin (茂林), 16km to the south. But it’s a delightful and highly accessible patch of nature.

Following Local Road 131 brought me to the back of a major temple I’d seen in the distance on my previous visit. I entered the grounds of Di Yuan Temple (諦願寺, literally “temple of hope”; open 4am to 8.30pm daily) without any expectations. Yet its location, overlooking and within a javelin throw of the Laonong River, is both commanding and vexing.

Having experienced a few of the typhoons and earthquakes that have ravaged Taiwan, I looked at this modern Buddhist complex and asked myself: Despite the concrete that’s been poured over the riverbank — and the prayers for protection that have surely been offered — how would it fare in a natural disaster?

Photo: Steven Crook

That question has already been answered, I learned after I got home. The groundbreaking ceremony was held back in 1996, but the first of three phases of construction wasn’t completed until 2016. A lack of funding was one reason for the slow progress. Another was that major repairs were needed in 2009, following Typhoon Morakot.

Walking from the parking lot and into the courtyard behind the main shrine, I encountered something I’ve never before come across in a place of worship: A pair of large and aggressive dogs.

The moment they saw me, these canines decided they didn’t like me one bit. I spent the rest of my visit looking around corners before making any moves.

Photo: Steven Crook

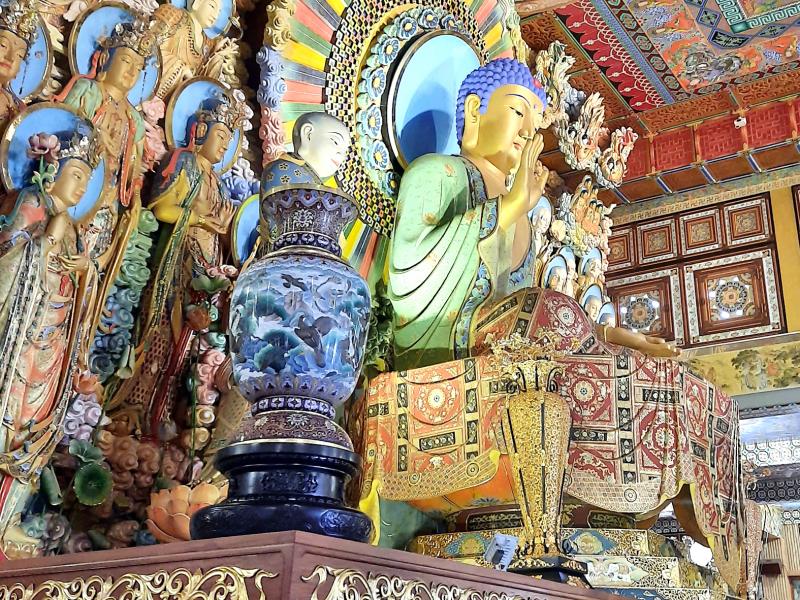

Externally, Di Yuan Temple isn’t very different to many other religious sites in Taiwan. Internally, however, there are several interesting features.

The main hall is gloriously colorful, and the Shakyamuni Buddha has a head of vividly blue curls. Hair of this hue is one of the Buddha’s 32 distinguishing physical characteristics. Next to the altar, there’s a concert piano. I don’t think I’ve ever witnessed a Buddhist service that included piano music.

On the far left of the hall, I found a Fasting Siddhartha statuette, and learned from it that in Chinese this kind of icon is called “Six Years of Austerity” (六年苦行). During the spiritual quest, preceding his enlightenment, the Buddha devoted six years to intense mental concentration and cutting all attachment to physical senses. It’s said that, toward the end of this period, he survived on a single grain of rice per day, and became skeletal thin.

Photo: Steven Crook

Behind the blue-haired Shakyamuni Buddha, 33 representations of Guanyin (觀音) face the back door. In Buddhism in Taiwan and China, this bodhisattva of mercy and compassion is female; elsewhere, he/she is usually regarded as male.

The central image is about the size of an adult and shows Guanyin sitting on a huge fish. This alludes to a story in which she appears in a market as a beautiful young woman holding a basket of fish, and requests that the men who admire her prove their worth by memorizing Buddhist sutras. It’s a very fine and intricate piece of work — but I was distracted by the bodhisattva’s enormous clodhopping feet, the significance of which I’ve not been able to discover.

Another highlight within the complex is a striking Reclining Buddha. Weighing seven tonnes, 7.5m in length, and carved from a single camphor tree, it’s claimed to be the largest camphor-wood Buddha in East Asia. An adjacent chamber held a somewhat smaller Buddha, also reclining and still wrapped in plastic.

Photo: Steven Crook

A patch of land near the parking lot is populated by gray statues of arhats, individuals who have made great progress toward enlightenment, but have not attained a state of Buddhahood.

One online source puts the number of arhat statues beside Di Yuan Temple at “more than 500,” and points out that no two are the same. Each statue bears a number, but I didn’t see a master list anywhere. Serious Buddhists may look askance at my choosing a favorite arhat. But who can resist the charm of the bald-headed gentleman who, while in deep contemplation, strokes his waist-length eyebrows?

Steven Crook has been writing about travel, culture and business in Taiwan since 1996. He is the author of Taiwan: The Bradt Travel Guide and co-author of A Culinary History of Taipei: Beyond Pork and Ponlai.

Nine Taiwanese nervously stand on an observation platform at Tokyo’s Haneda International Airport. It’s 9:20am on March 27, 1968, and they are awaiting the arrival of Liu Wen-ching (柳文卿), who is about to be deported back to Taiwan where he faces possible execution for his independence activities. As he is removed from a minibus, a tenth activist, Dai Tian-chao (戴天昭), jumps out of his hiding place and attacks the immigration officials — the nine other activists in tow — while urging Liu to make a run for it. But he’s pinned to the ground. Amid the commotion, Liu tries to

The slashing of the government’s proposed budget by the two China-aligned parties in the legislature, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), has apparently resulted in blowback from the US. On the recent junket to US President Donald Trump’s inauguration, KMT legislators reported that they were confronted by US officials and congressmen angered at the cuts to the defense budget. The United Daily News (UDN), the longtime KMT party paper, now KMT-aligned media, responded to US anger by blaming the foreign media. Its regular column, the Cold Eye Collection (冷眼集), attacked the international media last month in

A pig’s head sits atop a shelf, tufts of blonde hair sprouting from its taut scalp. Opposite, its chalky, wrinkled heart glows red in a bubbling vat of liquid, locks of thick dark hair and teeth scattered below. A giant screen shows the pig draped in a hospital gown. Is it dead? A surgeon inserts human teeth implants, then hair implants — beautifying the horrifyingly human-like animal. Chang Chen-shen (張辰申) calls Incarnation Project: Deviation Lovers “a satirical self-criticism, a critique on the fact that throughout our lives we’ve been instilled with ideas and things that don’t belong to us.” Chang

Feb. 10 to Feb. 16 More than three decades after penning the iconic High Green Mountains (高山青), a frail Teng Yu-ping (鄧禹平) finally visited the verdant peaks and blue streams of Alishan described in the lyrics. Often mistaken as an indigenous folk song, it was actually created in 1949 by Chinese filmmakers while shooting a scene for the movie Happenings in Alishan (阿里山風雲) in Taipei’s Beitou District (北投), recounts director Chang Ying (張英) in the 1999 book, Chang Ying’s Contributions to Taiwanese Cinema and Theater (打鑼三響包得行: 張英對台灣影劇的貢獻). The team was meant to return to China after filming, but